THE DIVE THAT CHANGED EVERYTHING

How a 19-Year-Old West Virginia Mechanic Broke Every Rule, Outflew the Luftwaffe’s Elite, and Accidentally Rewrote the Physics of Air Combat

On December 20, 1943, the skies above Bremen were a killing ground.

Below, hundreds of American B-17s and B-24s flew toward Germany’s industrial north. Above them, swirling like predatory birds, the Jagdgeschwader—Hitler’s fighter wings—climbed to intercept. By late 1943, deep-penetration raids into Germany were so costly that American bomber crews spoke about their 25-mission tour as a mathematical impossibility. Losses sometimes exceeded one in every five aircraft.

Into this sky flew Second Lieutenant Charles “Chuck” Yeager, nineteen years old, eight missions into a war he had never expected to fight.

At 7:23 a.m., tracer fire stitched the air behind his P-51 Mustang. A Messerschmitt Bf 109, flown by Unteroffizier Ludwig Franzisket—a hardened Luftwaffe fighter pilot with eleven confirmed kills—was closing for the kill. Yeager was low on fuel, nearly out of ammunition, and far from friendly support.

American doctrine said one thing:

Hold formation.

Fly textbook maneuvers.

Never break discipline.

In the next thirty seconds, Yeager would shatter that doctrine and survive by inventing—accidentally—what would become the foundational principle of modern air combat.

But to understand why that moment mattered, we must understand why the U.S. Army Air Forces were bleeding to death in the winter skies over Europe.

THE CRISIS OF 1943: A CAMPAIGN ON THE EDGE OF COLLAPSE

In August and October of 1943, the Schweinfurt–Regensburg raids shredded the Eighth Air Force. Sixty bombers were lost one day. Sixty-two on another. Hundreds of men were killed or captured.

The reason: escort fighters could not go far enough.

The P-47 Thunderbolt and P-38 Lightning could shield the bombers only until the German border. After that, they turned back—and the Luftwaffe descended in packs.

The strategic bombing campaign, cornerstone of Allied strategy, was failing. At this trajectory, the U.S. could lose the air war.

The brand-new P-51 Mustang, equipped with a Packard-built Rolls-Royce Merlin engine, had the range to change everything. But even with the right machine, American pilots were dying at ratios that alarmed senior commanders.

The problem wasn’t the aircraft.

It was the doctrine.

THE WRONG INSTRUCTIONS FOR THE WRONG WAR

American fighter doctrine in 1943 still reflected the thinking of the 1920s Air Corps Tactical School. It emphasized:

rigid formations

coordinated turns

altitude preservation

strict hierarchy

minimal individual initiative

The manual was clear: break formation and you endangered the group.

German pilots ignored all of this.

Having honed their skills over Spain, France, Britain, and Russia, Luftwaffe Experten relied on:

decentralized decision-making

independent maneuver

the flexible “finger-four” formation

energy management

vertical maneuvering

They were hunters. They stalked weaknesses. They used speed and altitude like currency.

Men like Adolf Galland, Günther Rall, Egon Mayer, Walter Nowotny, and Johannes Steinhoff had disproven every assumption American officers still taught.

By late 1943, the kill ratios reflected it brutally:

German fighters were destroying three to four American aircraft for every one they lost.

The U.S. Army Air Forces needed innovation. It arrived from the unlikeliest source imaginable: a skinny mechanic from West Virginia who hunted squirrels for dinner.

THE BOY FROM HAMLIN

Charles Elwood Yeager grew up in Hamlin, West Virginia, during the Great Depression. His father worked the gas fields and coal plants. Money was scarce. Meals were earned by hunting—silent, patient, precise.

Yeager had something else: preternatural vision. His eyesight measured 20/10—twice as sharp as average. He could spot a squirrel’s ear at 300 yards.

He enlisted in the Army Air Forces in 1941—not to fly, but to turn wrenches. As an enlisted mechanic, he serviced Airacobras in Nevada. In 1942, facing catastrophic pilot shortages, the Air Force created the “flying sergeant” program.

Yeager volunteered.

His instructors were stunned. He absorbed flying instinctively. Aircraft felt like extensions of his muscles. He graduated near the top of his class.

By November 1943, he was in England—young, unpolished, and almost dangerously fearless.

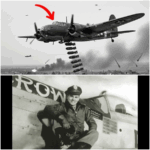

He flew a P-51B he named Glamorous Glen, after his girlfriend, Glennis Dickhouse.

His squadronmates were college-educated, polished, confident.

Yeager was a nineteen-year-old with an Appalachian drawl, oil-stained hands, and a hunter’s instinct.

That instinct would save his life—and reshape air combat.

OVER BREMEN: THE IMPOSSIBLE DIVE

On his eighth mission, escorting bombers toward Bremen, Yeager spotted a flicker of movement. Franzisket, the Luftwaffe hunter, was already sliding behind him.

Cannon rounds flashed past Yeager’s canopy.

Doctrine urged him:

maintain altitude

execute a standard break

stay in formation

Instead, he did something suicidal.

He rolled inverted and dove vertically toward the ground.

It was a maneuver every American pilot was taught never to attempt against a Bf 109.

German fighters, with their fuel-injected engines, should have held the advantage in negative-G dives. The P-51’s carbureted Merlin engine should have sputtered.

But as Yeager screamed downward, something unexpected happened.

The Mustang accelerated faster.

Much faster.

At 450 mph, then 475, then 500—past speeds the tactical school considered practically unreachable—the Mustang began outrunning its pursuer.

Franzisket followed, firing, but his shots fell behind.

At roughly 800 feet, Yeager pulled up with all his strength. The Mustang shuddered. His vision tunneled from G-forces. The wings flexed dangerously.

The P-51 leveled out. Franzisket tried to recover, but he bled energy—slowing to 320 mph.

Yeager reversed, climbed into the German’s blind spot, and fired a three-second burst.

The 109 spiraled down trailing smoke.

A nineteen-year-old had just performed what modern aviators would call a high-speed yo-yo maneuver.

None of it was in the manual.

“THAT IS IMPOSSIBLE.”

When Yeager landed and described the engagement, squadron leadership dismissed him outright.

“You cannot outdive a Messerschmitt,” Major Thomas Hayes told him. “Physics says so.”

Intelligence officers doubted his judgment.

Other pilots assumed adrenaline clouded his memory.

Gun-camera footage was blurred from the dive.

But Yeager wasn’t alone for long.

Within weeks:

Lt. William Wisner performed the same maneuver.

Another P-51 pilot escaped two Fw 190s with a vertical dive.

Capt. Don Blakeslee, commander of the elite 4th Fighter Group, conducted controlled test dives.

His findings were unequivocal:

At extremely high speeds, the P-51B could out-accelerate and out-maneuver every German fighter in existence.

The Mustang’s supercharged Merlin engine, designed for high altitude, produced unexpected power retention at high-speed, low-altitude dives.

The aircraft’s laminar-flow wing, optimized for speed, produced less drag in the dive than engineers predicted.

Blakeslee submitted a report.

A storm erupted.

THE FIGHT FOR NEW DOCTRINE

Senior officers were furious. Accepting Blakeslee’s conclusions meant admitting that decades of Air Corps dogma were fundamentally wrong.

Colonel Hubert Zemke—an ace but also a doctrinal purist—dismissed the finding as “reckless cowboy flying.”

Others argued the physics were impossible.

The tactical school insisted:

hold formation

maintain altitude

never dive away

never sacrifice position for speed

Buckling under entrenched culture, the bureaucracy nearly buried the data.

Then Major General William Kepner intervened.

A veteran of World War I dogfights, Kepner had no patience for outdated rules.

“Gentlemen,” he said, “I don’t care what the manuals say. I care about kill ratios.”

He authorized:

aggressive dives

independent initiative

breaking formation when necessary

vertical maneuvering

energy fighting

It was the most radical tactical shift in U.S. fighter doctrine since the armistice of 1918.

And it came not from theory—but from Yeager’s near-fatal dive.

BIG WEEK: PROOF UNDER FIRE

In February 1944, the Eighth Air Force launched Big Week—a massive coordinated assault on Germany’s aircraft factories.

For the first time:

P-51 Mustangs, using Yeager’s and Blakeslee’s new tactics, escorted bombers all the way to their targets.

The results were immediate.

Over Berlin, March 3, 1944, Yeager and Lt. “Bud” Anderson dove at 600 mph through a formation of Bf 109s led by ace Heinrich Bär.

Elite German pilots—pilots who once dictated combat terms—were suddenly on the defensive.

Aggressive diving attacks

speed retention

individual initiative

= air superiority.

Kill ratios skyrocketed.

January 1944: 2.1 to 1

April 1944: 4.3 to 1

June 1944: 6.1 to 1

The Mustang became a terror. German pilots wrote privately that American fighters seemed to fall from the sky “like hawks, too fast to escape.”

Johannes Steinhoff, future Bundeswehr general, noted:

“By mid-1944, the Americans had mastered the vertical plane.

Our advantages disappeared.”

The Luftwaffe began burning through its veteran aces. Replacements were rushed into combat with minimal training.

The strategic bombing campaign, once on the brink of collapse, now surged.

Thousands of bomber crewmen survived missions that would have killed them in 1943.

YEAGER VS. EDGER: THE FINAL CONFIRMATION

On May 8, 1944, over Brunswick, Yeager met one of the Luftwaffe’s finest: Georg-Peter Eder, thirty-six kills, flying a brand-new Bf 109G-10.

Eder initiated a high-speed diving attack.

Yeager dove in response.

They collided head-on, fired, missed.

Yeager broke downward again—daring Eder to follow.

Eder did.

His 109 couldn’t hold the vertical energy.

G-forces robbed him of vision.

He emerged from the dive slow and vulnerable.

Yeager reversed, slid behind him, and fired.

Eder escaped—but barely. His 109 was written off.

After the war, Eder wrote:

“The American pilot executed maneuvers I believed impossible.

He dove away and somehow ended behind me.”

THE DEATH OF THE LUFTWAFFE

By summer 1944, the Luftwaffe collapsed under the pressure:

too few veteran pilots

too few aircraft

too little fuel

Mustangs dominating at every altitude and angle

What killed it wasn’t just Allied industry or pilot numbers.

It was the sudden, explosive superiority of American aerial tactics—born from Yeager’s dive and institutionalized by commanders willing to listen.

Bomber loss rates plummeted:

20% in late 1943

under 4% by June 1944

The air war turned so decisively that ground commanders—once terrified of German fighters—now complained there weren’t enough Luftwaffe aircraft left to shoot at.

AFTER THE WAR: WHAT ENERGY FIGHTING BECAME

The principles Yeager accidentally uncovered became the first chapter of every jet fighter syllabus:

altitude = potential energy

speed = survival

the vertical plane dominates

maneuvering is three-dimensional

momentum wins fights

The high-speed yo-yo, lag pursuit, lead pursuit—these are standard language for pilots of the F-16, F/A-18, F-22, and F-35.

Every pilot flying today, from Pensacola to Nellis to Miramar, learns Yeager’s lesson:

Break the rules—if obeying them gets you killed.

THE LIFE THAT FOLLOWED

Yeager was shot down once—March 1944—evaded capture with help from the French Resistance, and returned to fly more missions.

He ended the war with 11.5 confirmed kills.

Afterward, he became a test pilot.

On October 14, 1947, Yeager strapped himself into the Bell X-1, broke the sound barrier, and became the most famous test pilot in American history.

He retired as a brigadier general in 1975.

He died on December 7, 2020, at the age of 97.

THE LESSON: INNOVATION DOESN’T COME FROM DOCTRINE

The significance of Chuck Yeager’s dive cannot be overstated.

It teaches a universal truth:

Institutions resist change until someone forces them to accept reality.

By all logic, Yeager should have died over Bremen.

Instead, he lived because he abandoned rules that didn’t fit the fight.

And in doing so, he saved thousands of airmen he never met.

The textbooks often focus on the glamour of the P-51, the brilliance of American engineering, the scale of American industry.

But the air war was changed by something far more human:

A nineteen-year-old Appalachian mechanic

—without connections,

—without prestige,

—without pedigree,

who reacted with pure instinct

and discovered that the impossible was simply the untried.

Sometimes, the future belongs not to the experts,

but to the kid who doesn’t know what can’t be done.

If you’d like:

— a shorter 1,500-word magazine cut

— a more cinematic version

— a chapter-length 6,500-word expansion

— or a companion article on P-51 design evolution or Luftwaffe counter-tactics

I can write those too.

News

The Bismarck – How the World’s Most Feared Battleship Lasted Only Eight Days at Sea

At 2:48 a.m. on May 24, 1941, in the freezing darkness of the Denmark Strait, a British officer lifted his…

They Said the Shot Was ‘Impossible’ — Until He Hit a German Tank 2.6 Miles Away

At 10:42 a.m. on December 1, 1944, a young American lieutenant leaned into the eyepiece of a gun sight and…

Japanese Couldn’t Believe This Shot-Up B-25 Sank 2 Ships — Then Saved His Squadron

Into the Teeth of Hell: Major Raymond Wilkins, Bloody Tuesday, and the American Spirit in War On the morning of…

Germans Couldn’t Believe This Destroyer Rammed Them — Until 36 Fought Hand-To-Hand With Coffee Mugs

Coffee Mugs and Courage: How USS Buckley Turned a Night Battle into an American Legend On an ordinary day at…

They Banned His Forest Floor Sniper Hide — Until It Took Down 18 Germans

THE SOLDIER IN THE MUD How a South Philadelphia Rifleman Broke the Rules, Revolutionized Sniper Tactics, Was Court-Martialed—And Quietly Saved…

They Mocked His ‘Medieval’ Crossbow — Until He Killed 9 Officers in Total Silence

🤫 The Silent Assassin of the Hürtgen: How a Philly Dockworker Reintroduced the Crossbow to WWII Private First Class…

End of content

No more pages to load