**THE COOK WHO STOPPED AN ARMY:

Sergeant José Calugas and the Day a Mess Sergeant Became a One-Man Artillery Crew**

On the afternoon of January 16, 1942, the rice pots were almost clean.

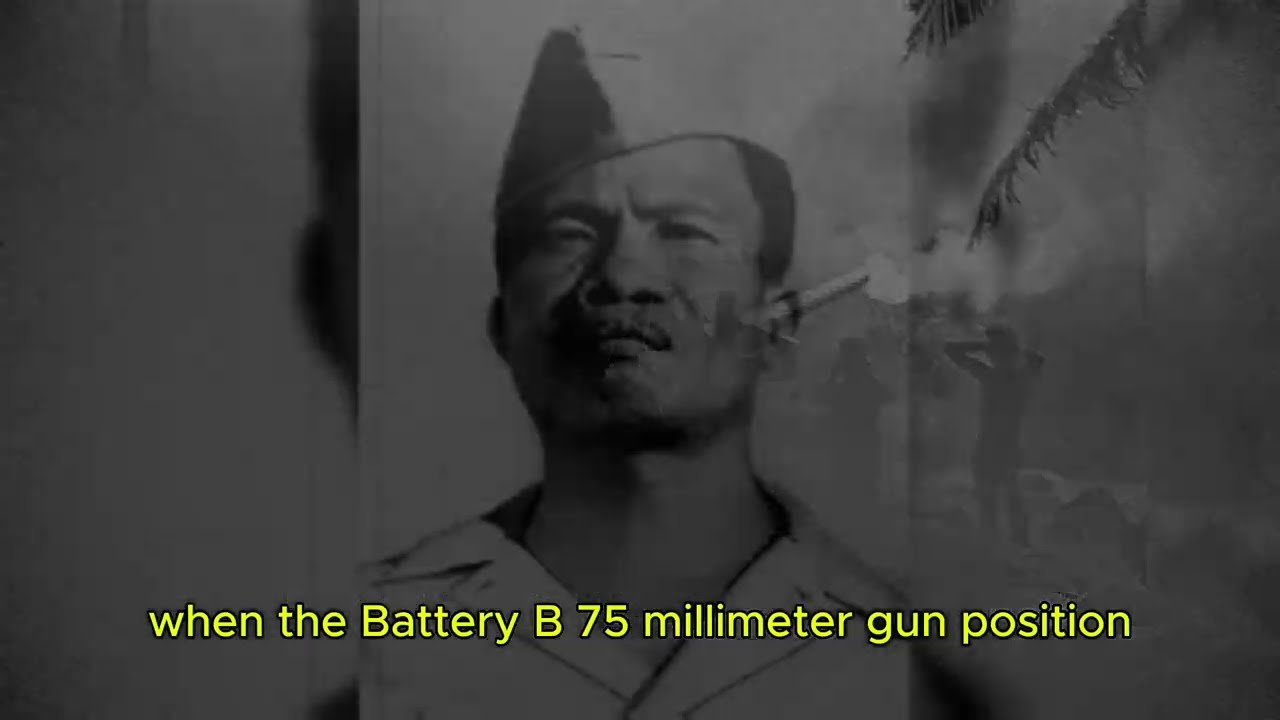

Sergeant José Calugas—34 years old, wiry, disciplined, a twelve-year veteran of the Philippine Scouts—stood beside his field kitchen in Bataan, scrubbing soot and rice starch from heavy metal cauldrons. Around him, the wheeze of jungle heat, the distant crackle of gunfire, and the deep throat of artillery shaped the soundscape of a peninsula under siege.

Then, at 1:40 p.m., something changed.

From the north, roughly 1,000 yards away, the steady thump of Battery B’s 75-mm field gun—one of the few pieces of American artillery still functioning on Bataan—abruptly went silent.

Silence, on that peninsula, was never good news.

Calugas froze for half a second. He had served the gun crews lunch just an hour earlier—rice and canned salmon, rationed tightly because the Scouts were already on half rations. Now the gun had stopped firing. And in the Battle of Bataan, when a gun went quiet, it tended to stay that way.

In nine days of fighting, the Scouts had lost eleven artillery crews. Every position that fell silent meant dead men—or men too wounded to fight. And every missing gun meant the Japanese advance would surge forward.

Across Bataan, doctrine was collapsing under pressure. Everything—food, ammunition, medicine, sleep—was in short supply. Courage was not.

José Calugas, mess sergeant, cook, father, and artillery-trained scout whose job description no longer mattered, put down his scrub brush.

“I knew,” he would say years later, “that someone had to bring that gun back to life.”

He gathered volunteers.

And he ran.

A Professional Soldier in a Starving Army

Before he became an icon of improvised heroism, Calugas had lived the disciplined, steady life of a career soldier.

Born in Iloilo Province, he enlisted in the Philippine Scouts in 1930 at age 23, completed basic training at Fort Sill, Oklahoma, and graduated from artillery school. Assigned first to the 24th Field Artillery at Fort Stotsenberg and later transferred to the 88th Field Artillery Regiment, he built the kind of career that rarely makes headlines but forms the spine of any army: reliable, knowledgeable, admired by his superiors.

In 1941 he was a mess sergeant—a job as vital as any rifle in an army that needed calories to fight. His responsibilities were simple: feed the men, keep morale alive one warm meal at a time.

But nothing on Bataan was simple after January 7, 1942.

American and Filipino forces had retreated into the narrow peninsula ten days earlier. Eighty thousand troops and more than twenty-six thousand civilians were now trapped on a jungle landmass barely 60 miles long and 20 miles wide. The Japanese Fourteenth Army, under General Masaharu Homma, controlled the land to the north and poured artillery, infantry, and aircraft into the bottleneck.

Homma had promised Tokyo he would take the peninsula in fifty days.

His timetable was working—slowly, bloodily—because the Americans and Filipinos were starving.

Rice stocks had been intended to feed 25,000 troops for three months. They now had to stretch across 100,000 souls. Horses were slaughtered, then mules, then carabaos. Within weeks the average soldier was consuming roughly 900–1,200 calories per day while performing the labor of war.

Still, the Scouts held.

The Philippine Scouts—Filipino enlisted men under American officers—were the elite of America’s prewar Pacific forces. They had fought insurgents, jungle bandits, and foreign armies since 1901. They were professionals, tough and disciplined. Battery B of the 88th Field Artillery was one of the few units still able to deliver regular counter-fire against the Japanese.

Until 1:40 p.m. on January 16.

“Every Man Knew the Odds”

Calugas heard the barrage first: Japanese shells walking across the treeline, a rolling avalanche of sound that lifted debris into the air. Then the gun was silent. No counter-fire. No shouted orders. No signal rockets.

He understood what that silence likely meant: the gun had been hit, the crew casualties, the weapon disabled.

Without its fire, the Japanese infantry column pushing toward the Scout line would reach American positions within minutes.

Calugas scanned the horizon, then called out for volunteers—mess crews, nearby stragglers, men on the periphery. Sixteen answered.

Ahead lay 1,000 yards of rice paddies. Open ground. No cover. Japanese fighters were already prowling overhead. The artillery was still falling.

Most men who crossed open fields on Bataan did not reach the other side alive.

Still, Calugas ran.

One by one, volunteers fell behind or fell wounded. Machine gun bursts peppered the paddies; artillery shells wrenched fountains of mud into the air. At 400 yards, there were six volunteers left. At 200, there were three.

Calugas kept running.

Eventually, only he reached the shattered gun pit.

A 1,500-Pound Weapon and a Single Cook

The scene was a devastation he would remember for the rest of his life.

The 75-mm gun had been blown off its firing platform, lying sideways in a crater, trails twisted, carriage partly buried. The crew was dead or dying. One private, hit in the shoulder, was conscious and trying to crawl.

The Japanese column was closing to within 300 yards.

Calugas needed that gun upright. He needed a crew. He needed time.

He had none.

He pulled the wounded private to his feet, scanned the treeline, and yelled. Against all odds, two more Scouts—a pair of gunners from a neighboring position—ran into the bombardment to join him.

Four men. One semi-functional gun. A Japanese infantry column bearing down.

Artillery school had been twelve years earlier, but muscle memory never truly fades. Calugas checked the recoil system, the breach block, the trunnions. The weapon was damaged but not destroyed.

They heaved.

Six inches of movement. Then six more. Sweat, mud, blood, burned powder. Under fire the men wrestled the 1,500-pound gun back into alignment, shoved, lifted, cursed, braced—until finally they levered the weapon back onto its firing platform.

Calugas spun the elevating handwheel. Functional.

He cranked the traverse. Functional.

He opened the breach.

Clear.

The ammunition locker—miraculously—was intact.

He selected an armor-piercing round. The Japanese column was crossing a wooden footbridge 200 yards away. Trucks, infantry, horse-drawn artillery—all bunched up.

A perfect target.

He fired.

The bridge disintegrated in a burst of splinters and flame. The lead truck plunged into the creek. Chaos rippled through the Japanese formation.

Another round—high explosive—slammed into the backup trucks. Ammunition inside detonated, unfolding a secondary blast that tore open the column’s heart.

The Japanese halted.

They had been on the brink of breaking the American line. Now they were pinned and burning.

Calugas kept firing.

High explosive into infantry. Armor-piercing into vehicles. Shell after shell into water where Japanese troops tried to ford the creek.

Then the counterfire came.

“Move, Fire, Hide”

At first it was a few shells. Then dozens. Then every Japanese battery in range.

They had identified the gun. They knew where the shells were coming from. They would smother the crater until nothing inside survived.

Calugas had a choice: keep firing from the fixed pit and die in minutes, or improvise.

He improvised.

He ordered the men to drag the gun into the nearby woods—thirty yards of jungle canopy thick enough to obscure sightlines. Japanese observers would lose visual confirmation. Calugas would use the trees as a movable shield.

Shoot. Move. Hide. Repeat.

It was artillery guerrilla warfare.

They pushed the gun into the jungle just as the first counter-battery salvo hit the crater. Dirt and shrapnel blasted skyward.

As soon as the barrage paused, the four men rolled the gun back to the crater’s edge, fired several shells at Japanese units trying to regroup north of the ruined bridge, then muscled the weapon back into cover.

Seconds later another rain of explosions pulverized the gun pit they had just vacated.

For six hours, this dance continued.

Move gun into position. Fire three to five rounds. Haul the gun back into the jungle. Brace for impact. Repeat.

Exhaustion blurred the hours, but discipline held. Calugas directed fire, selected ammunition, called corrections, watched impact points. The other men—half-starved, dehydrated, burned from heat and recoil—followed his cadence.

By evening they had fired forty-seven rounds.

The Japanese column was shattered.

Vehicles burned. Bodies covered the roadway. Infantry had dug in, unable to advance. The attack on that sector had died.

Battery B’s gun had given the rest of the 88th Field Artillery time to withdraw to new positions. Without Calugas, that withdrawal—and the stability of the entire defensive line—might have been impossible.

But his day was not over.

The gun had to be saved.

And so did his kitchen.

Evacuation Under Fire

Dusk offered a few minutes of grace.

Visibility worsened; Japanese gunners’ accuracy fell. Calugas seized the moment. He flagged down two trucks from a retreating supply column, explained the situation, and convinced the drivers to help evacuate both the gun and the mess equipment.

The trucks rumbled to the treeline where the 75-mm gun lay hidden. Under sporadic fire, the crew loaded the weapon.

The first truck pulled away at 18:30.

Japanese artillery walked its fire down the road after them—fifty yards behind, then forty, then thirty. But the driver pushed the truck hard, bouncing over ruts and roots while Calugas and the crew braced the gun.

They reached the new gun line at 19:00.

The gun was intact.

The second truck mission—retrieving Calugas’s field kitchen—was equally harrowing but successful. Pots, pans, rice sacks, whatever food remained, all were saved.

By 21:00, while other men collapsed in the mud, Calugas had reassembled the kitchen and served beans and rice to exhausted survivors.

Then he cleaned his equipment.

At midnight, he finally rested.

Medal of Honor—Buried Before It Was Earned

The report of his actions moved fast.

By January 18 it had reached General Douglas MacArthur on Corregidor. The general, who had seen legion acts of heroism in his career, singled this one out. He recommended Sergeant José Calugas for the Medal of Honor—the first Filipino American recipient in World War II.

The War Department approved it on February 24.

But there was a problem.

Bataan was dying.

The defenders were starving. Malaria, dysentery, dengue fever, and exhaustion raked the ranks more lethally than bullets. Ammunition was gone. Medicine was gone. Horses, mules, even snakes and iguanas had been eaten. The Scouts, always the hardest-fighting force on the peninsula, had wasted to ghosts.

In March, President Franklin Roosevelt ordered MacArthur to evacuate to Australia. Command shifted to General Jonathan Wainwright, who knew grim truth: no reinforcements, no resupply, no hope.

It was only a matter of time.

In early April, the Japanese launched their final offensive. Fresh troops. Heavier artillery. Constant air attack. The American-Filipino line collapsed.

On April 9, 1942, Major General Edward King surrendered 76,000 troops.

The Bataan Death March began.

Before joining the column, Calugas faced one more danger.

The Japanese high command monitored American transmissions. They knew someone named “Calugas” had been recommended for America’s highest honor. They would torture or execute him instantly if they identified him.

So Calugas buried the general order announcing his Medal of Honor. He dug a pit, hid the paper beneath a tree, and ordered every man in Battery B to forget he was anything other than a cook.

The men agreed.

Silence kept him alive.

The Death March and the Camps

The march was 65 miles of sun, dust, misery, and murder.

No water. No food. No mercy.

Guards beat, bayoneted, and shot prisoners who stumbled. Men died where they fell, and others were beaten for trying to help them. Filipino civilians who tried to offer water were killed.

Calugas walked through the heat with malaria burning through him. His fever—genuine but manipulated—became his shield. Japanese guards avoided sick prisoners for fear of infection. He exaggerated his symptoms, wrapped himself in scrap cloth, shivered theatrically, and avoided eye contact.

He stayed in the center of the column—the safest place.

Still, he watched friends collapse and die. He stepped over bodies he could not help. He saw the road lined with the swollen corpses of men who had survived four months of combat only to die of thirst on the roadside.

At San Fernando, men were packed into rail cars—100 men in cars built for 30. The interior temperature soared past 120 degrees. Some died standing.

After the train journey, there were eight more miles to Camp O’Donnell.

Camp O’Donnell was hell.

Built for 10,000 troops, it held 50,000. One water tap. No sanitation. Dysentery, malaria, cholera, pneumonia.

Thirty to fifty prisoners died per day. Some days, a hundred.

Calugas volunteered for burial detail—a job revolting in its horror but safer than rotting in a barracks. Movement meant circulation. Circulation meant life.

He endured nine months.

He watched thousands die.

He survived.

Civilian Laborer—Secret Resistance Fighter

In January 1943, a Filipino provincial official petitioned for Calugas’s release. The Japanese occasionally reassigned Filipino prisoners to labor in rice mills and farms. The official claimed Calugas was needed for agricultural work.

The Japanese approved it.

On January 15, 1943—exactly one year and one day after his act of heroism—Sergeant José Calugas walked out of Camp O’Donnell.

He had lost forty pounds. He bore scars and the deep exhaustion of men who have lived too many lifetimes in too little time.

He was assigned to a rice mill in Pampanga Province.

But he had no intention of spending the rest of the war milling rice for Japan.

The guerrillas found him first.

Resistance fighters operating under American officers Major Robert Lapham and Captain Harry McKenzie had heard whispers about a Scout mess sergeant who had become a one-man artillery crew. They approached him discreetly at the mill. They asked if he was willing to help.

He said yes.

For six months, Calugas became a spy—collecting patrol schedules, supply movements, garrison strengths, road conditions. He passed the intelligence to guerrillas disguised as vegetable vendors.

Every week, Japanese convoys in Pampanga suffered more ambushes.

Every week, Calugas transmitted more data.

By October 1943, Lapham’s unit—Squadron 227 “Old Bronco”—decided Calugas was more valuable as a soldier than as a spy.

They arranged his escape.

He walked into the jungle and did not return.

Guerrilla Officer

Squadron 227 was a mixed unit of 300 fighters—former Scouts, farmers, students, and escaped POWs. They had rifles, Arisaka carbines, some captured machine guns, and near-zero ammunition. But they had cunning, terrain knowledge, and absolute commitment.

Lapham interviewed Calugas personally.

He verified the Medal of Honor citation.

He promoted him to second lieutenant on the spot.

Calugas took command of the weapons platoon.

From late 1943 to 1944, he led seventeen successful raids on Japanese supply depots and garrisons—without losing a single man. He struck at night, disappeared at dawn, sabotaged Japanese logistics, and trained guerrilla fighters.

The Japanese placed a price on his head.

They did not know he had a Medal of Honor.

They just knew he was hurting them.

Liberation and Recognition

In January 1945, MacArthur returned to Luzon.

Guerrillas surged into action. Calugas’s platoon blew bridges, ambushed patrols, disrupted communications. American forces advanced rapidly, thanks in part to guerrilla intelligence.

By April, Luzon was largely liberated.

Calugas returned to U.S. Army command.

And on April 30, 1945—more than three years after his actions on Bataan—he finally received the Medal of Honor.

The ceremony at Camp Olivas was simple but profound. Major General Richard Marshall read the citation aloud as Calugas, in a new uniform, stood ramrod straight:

“For conspicuous gallantry and intrepidity in action above and beyond the call of duty…”

Marshall placed the ribbon around his neck.

After three years of horror—death march, prison camp, forced labor, guerrilla warfare—the moment must have felt unreal.

Calugas immediately accepted American citizenship.

Then he accepted a commission as a lieutenant.

He would remain a U.S. Army officer for another twelve years.

A Life Rebuilt

After the war, Calugas served in Okinawa, the Ryukyu Islands, Fort Sill, and Fort Lewis. He brought his family from the Philippines to the U.S. one by one. He earned his high school equivalency certificate at 47. He retired from the Army in 1957 as a captain.

Then, remarkably, he enrolled at the University of Puget Sound.

He graduated in 1962 at age 55 with a degree in business administration.

He worked for Boeing.

He farmed.

He raised four children.

He spent fifteen years building the Bataan-Corregidor Survivors Association, helping veterans process trauma they had locked away for decades.

He rarely spoke about himself.

He insisted the Medal of Honor belonged to the men who died on Bataan.

He was just the one chosen to wear it.

José Calugas Sr. died on January 18,

News

My Family Missed My Wedding For My Sister, But My Castle Ceremony Changed Everything…..

My Family Missed My Wedding For My Sister, But My Castle Ceremony Changed Everything….. I was pinning my veil in…

The Germans mocked the Americans trapped in Bastogne, then General Patton said, Play the Ball

On a gray December morning in 1944, as snow fell over the forests of Belgium and Luxembourg, Allied commanders stared…

A 1912 Wedding Photo Looked Normal — Until They Zoomed In on the Bride’s Veil

On a quiet Saturday afternoon in downtown Chicago, Detective Rebecca Walsh walked into Murphy’s Antiques with one simple goal: find…

“Please Marry Me”, Billionaire Single Mom Begs A Homeless Man, What He Asked In Return Shocked…

The crowd outside the Super Save Supermarket stood frozen like mannequins. A Bentley Sleek had just pulled up on the…

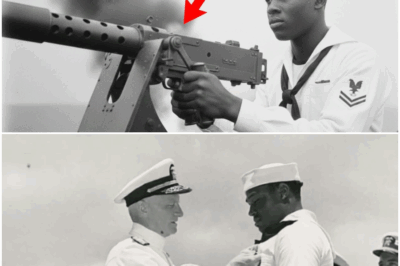

How One Black Cook’s “ILLEGAL” AA-Gun Grab Shook Pearl Harbor — And Forced the Navy to Change

On the morning of December 7, 1941, Pearl Harbor looked like a postcard. The water inside the harbor was calm…

She Was Serving Coffee in the Briefing Room — Then the Admiral Used Her Call Sign and the Room Froze….

She Was Serving Coffee in the Briefing Room — Then the Admiral Used Her Call Sign and the Room Froze…….

End of content

No more pages to load