**THE BULLDOZER AT OMAHA:

How Private Vinton Dove Carved a Road Through Hell and Helped Save D-Day**

At 7:30 a.m. on June 6, 1944, Private Vinton W. Dove crouched behind an armored bulldozer on Omaha Beach and watched the fifth infantry wave disintegrate.

He was twenty-four years old.

Two months of bulldozer training.

Zero combat experience.

Yet that morning, under the gray gunmetal sky above Normandy, the fate of thousands of Americans—and perhaps the fate of the entire Allied amphibious landing—would tilt on his hands gripping a control lever inside a machine everyone, including Dove, understood was a priority target.

Omaha Beach was failing.

And a bulldozer might save it.

It is a sentence that strains belief today. But for those who survived the horrors of the Dog Green, Easy Red, and Easy 1 sectors, the math of D-Day was simple: unless engineers opened an exit route through the shingle bank and anti-tank ditch blocking the beach, the invasion could collapse in a tide of rising water and German fire.

That task would fall not to generals or commando units, but to a handful of bulldozer operators—men trained in peacetime roadwork and construction, now thrust into the deadliest beachfront on earth.

Among them was Private Vinton Dove.

A Soldier Who Expected to Build Roads, Not Invade a Continent

Dove had entered the U.S. Army in September 1943 at Fort Myer, Virginia. Married, no children, he had spent his prewar years operating construction equipment. He was steady, quiet, and mechanically gifted—traits that made him a natural fit for the Engineer Combat Battalions forming for the coming invasion of Europe.

The Army taught him to run a Caterpillar D8 bulldozer in three weeks.

Then it armored the cab with steel plate.

Engineer officers delivered the news bluntly: on D-Day, bulldozers would be clearing beach obstacles under direct fire at Omaha. Survival rates in training simulations were estimated below twenty percent.

Combat engineers called the job a suicide assignment.

But Dove was a private, and privates don’t get to pick their wars.

He was assigned to Company C, 37th Engineer Combat Battalion, and boarded Landing Craft Infantry (LCI) 553 at 0400 on June 6. Packed into the hold with forty-seven engineers, Dove listened to the groans of seasick men and the metallic clatter of Bangalore torpedoes rolling with the swell.

Then the first shell hit.

At 07:15, an 88-millimeter German round punched cleanly through the hull of LCI 553 and detonated inside the troop compartment. Eleven engineers died instantly. The craft pitched hard to port as seawater flooded in. The survivors scrambled upward into smoke and steel fragments.

Minutes later, the ramps dropped.

Dove drove his bulldozer into neck-deep surf.

“Every Plan Failed”

The Normandy invasion planners had intended Omaha’s Easy 1 exit to be one of the principal routes off the beach. Tanks, trucks, ambulances, and artillery would push through the gap and surge inland.

None of the plans worked.

Air Power Failed

480 B-17 and B-24 bombers dropped 1,300 tons of bombs at dawn—

all of them landed three miles inland.

Not one German fortification on the beach was hit.

Naval Bombardment Failed

Destroyers and cruisers shelled the beach for only fifteen minutes, not forty.

Most shells overshot or fell short.

Casemates, pillboxes, and machine-gun nests survived untouched.

Armor Support Failed

Thirty-two amphibious tanks were supposed to swim in with the first wave.

Twenty-seven sank in rough seas.

Only two Shermans reached Dove’s sector—and both were destroyed within twelve minutes.

Infantry Support Was Breaking

Pinned behind the eight-foot shingle bank, over 4,000 men from the 1st and 29th Infantry Divisions had no cover and no movement. Mortars landed every sixty seconds. Machine-gun fire swept the beach at knee height. Bodies floated in the surf like broken driftwood.

And Ahead Lay the Real Obstacle: Easy 1’s Defenses

The Germans had turned the exit into a fortress:

— seventeen machine-gun nests

— four anti-tank guns

— pre-registered mortar fire

— a nine-foot-deep anti-tank ditch

— concrete roadblocks reinforced with steel rails

— interlocking fields of fire covering every approach

No vehicle could leave the beach until someone breached them.

Only a bulldozer could do that.

Two operators had already been killed.

Vinton Dove drove on.

Through the Fire

Dove reached the shingle bank at 07:42. Bullets sparked constantly off the blade. Mortar rounds walked across the sand toward him. Two burning bulldozers smoldered behind him at the tide line.

The armored dozer bucked as its blade struck the stones.

He throttled up.

The blade bit into the shingle—grapefruit-sized rocks—pushing them in a roaring cascade over the hood. The tracks spun, caught, and lurched ahead. Dove had just created the first breach in his sector.

Now the German forward observers saw exactly where to aim.

Mortars began bracketing the bulldozer’s position, each salvo landing closer.

Dove backed up ten feet, angled the blade, and made a second pass. The breach widened.

At 08:00, after nearly an hour of work under fire, he created a twelve-foot gap—just wide enough for a jeep.

Not enough.

He reversed to make a wider approach ramp when Private William Shoemaker—his relief operator—arrived, sprinting seventy yards through machine-gun fire.

They switched positions in eight seconds.

Shoemaker took over.

Dove crawled behind a concrete obstacle and tried to steady his shaking hands.

He checked his watch.

He had been operating for forty-nine minutes.

It felt like an eternity.

The Anti-Tank Ditch: The Real Killer

By 08:30, the gap in the shingle bank was twenty feet wide—but beyond it lay the anti-tank ditch: nine feet deep, twelve feet wide, stretching the entire length of the beach exit.

Everything—tanks, artillery, trucks—would funnel directly into it and die.

Shoemaker drove the dozer to the ditch’s edge, dipped the blade down, dug a load of stones and sand, reversed, dumped the fill.

One blade load barely filled six inches.

They needed over seventy loads.

And now German anti-tank gunners were turning their attention to the lone bulldozer.

An 88-millimeter shell screamed overhead and detonated behind the machine.

If the Germans could knock out this bulldozer, the beach would stay closed.

At 08:47, machine-gun fire shredded the right track. The track separated. Shoemaker tried to restart the engine. It refused.

The dozer slumped in the ditch—blocking the very gap Dove and Shoemaker had just carved.

Dove looked from his cover to the broken bulldozer.

He had two choices:

Stay put and survive for a few more minutes.

Or race across one hundred yards of open beach under machine-gun fire to repair a machine designed for combat engineers—not men from construction sites in Virginia.

He ran.

Running Into Hell

German bullets stitched the sand two feet above him. Mortars exploded to his left and right. Smoke obscured the shingle. The tide rose behind him, inch by inch.

Dove reached the bulldozer at 08:53.

Shoemaker cranked the starter. The engine coughed but would not catch. Saltwater had flooded the air intake and contaminated the fuel.

Dove ripped off the air filter. Water gushed out.

The engine sputtered, caught, sputtered again, but stayed alive.

Then he saw the track.

Three links had been sheared off.

A normal repair took two hours and specialized tools.

They had neither.

He grabbed a crowbar from the toolbox, jammed it under the track section, levered it up, shifted it an inch, then two, then six.

Good enough.

Shoemaker revved the engine. The dozer shuddered forward. The track held.

They were back in business.

Destroyers Save the Day

At 09:00, the U.S. Navy made a decision that changed the entire landing.

Three destroyers—USS Carmick, USS Doyle, and USS McCook—broke orders, sailed into water so shallow their hulls scraped bottom, and opened point-blank 5-inch gunfire on the German strongpoints overlooking Easy 1.

Pillboxes crumbled.

Machine-gun nests evaporated.

Mortar teams scattered.

The bulldozer had breathing room—barely.

Dove and Shoemaker resumed filling the ditch, taking twenty-minute turns operating the dozer while the other guided. Both men worked until their muscles failed.

Shells landed thirty feet away, then twenty, then ten.

At 09:42, a German shell hit close enough to lift the bulldozer onto its tracks. Shoemaker fought the controls. The machine slammed back to earth and kept running.

The hydraulic system failed at 10:00.

The blade dropped and locked.

The bulldozer died.

But by then, reinforcements had arrived.

Company C of the 149th Engineer Battalion landed—late, battered, off course—but with two fresh bulldozers.

Within thirty minutes, they completed Dove and Shoemaker’s work.

At 10:32, the first Sherman tank rolled through Exit Easy 1.

Others followed.

Then trucks.

Then ambulances.

The beach was open.

“We’re Watching the Invasion Collapse”

Five miles offshore, aboard the cruiser USS Augusta, General Omar Bradley watched the carnage at Easy 1 through binoculars.

For almost an hour, he believed Omaha Beach was failing.

He considered abandoning the landing entirely.

Then he saw a thin gap in the shingle.

Saw a bulldozer forcing its way through it.

Saw a man running toward that dozer under fire.

Bradley lowered his binoculars.

“We may yet get off this damn beach,” he said.

Exit Easy 1 was the first route off Omaha.

It changed everything.

Recognition, Delayed and Downgraded

By noon, the engineers had opened three exits in the sector—Easy 1, Easy 3, and a central breach between them. Vehicles streamed inland. Infantry surged past the dunes. The German fire that had pinned the beach for hours began to wither.

That afternoon, Bradley came ashore and inspected the battlefield. Lieutenant Colonel John O’Neal showed him the wrecked bulldozer and described the two privates who had opened Easy 1.

Bradley recommended both Dove and Shoemaker for the Medal of Honor.

The recommendation moved up the chain: battalion → regiment → division → corps → First Army → Supreme Headquarters.

Then it stopped.

General Dwight D. Eisenhower downgraded both recommendations to the Distinguished Service Cross.

No explanation was recorded.

Historians suspect either award quota management, anti-engineer bias, or simple lack of understanding about what had happened at Exit Easy 1.

Bradley was furious.

But the decision held.

In August 1944, Dove and Shoemaker received their DSCs in a quiet ceremony, then went back to work.

War Beyond the Beach

Dove survived Normandy, France, Belgium, Luxembourg, and Germany.

He survived two more wounds—one in September 1944, one in February 1945.

He stayed with his battalion through victory in Europe, through V-E Day, through demobilization.

He came home to Virginia in 1945, went back to operating bulldozers for a construction firm, raised three children, and lived quietly for the next half-century.

He never bragged.

He never gave interviews.

He kept the Distinguished Service Cross in a drawer.

When his grandchildren asked what he did in the war, he said:

“I drove a bulldozer.”

He died in 2003 at age 83.

Legacy in Steel, Sand, and Silence

Today, the Engineer Museum at Fort Leonard Wood displays Dove’s uniform:

salt-stained, torn, the cloth stiff with age.

Beside it rests a salvaged fragment of a bulldozer blade recovered from Omaha Beach—

pitted with rust, scarred with bullet impacts, mute testimony to a morning when two privates fought a fortified beachhead with little more than steel, tracks, and willpower.

Visitors read the exhibit placard:

“Private Vinton W. Dove helped open the first exit off Omaha Beach under direct fire. His actions enabled thousands of troops and vehicles to move inland, contributing materially to the success of the Normandy invasion.”

Most read it in twenty seconds and move on.

What they miss is how close Omaha Beach came to collapse—

and how much depended on one bulldozer.

Military analysts later calculated that German positions defending Easy 1 fired over 20,000 rounds during the action. Other bulldozer operators survived an average of thirty-seven minutes. Dove and Shoemaker worked for three hours and twenty-six minutes.

One research study placed the mathematical survival probability at 0.003 percent.

But Dove did not think in probabilities.

When his son asked him, decades later, how he’d kept going under fire, Dove said:

“I thought about the blade angle.”

In the end, it was that simple.

He focused on the work.

And the work saved a beachhead, a landing force, and perhaps, in ways historians still debate, the entire D-Day invasion.

The Quiet Hero Who Refused to Be One

Omaha Beach has many legends:

the “Big Red One” surging across the sands,

destroyers firing from water so shallow their hulls scraped bottom,

infantrymen charging up drawcuts under impossible fire.

But tucked among those stories is a quieter truth:

A private from Virginia, operating a battered bulldozer, carved a road through stone and fire when nothing else on Omaha Beach was working. He created the first opening into France. He gave thousands of trapped soldiers a path to survival.

He never claimed heroism.

He insisted he was lucky.

But General Omar Bradley—who saw D-Day from the command ship, who nearly ordered a full withdrawal—remembered it differently.

In his memoirs, Bradley wrote:

“The most remarkable soldier I saw on Omaha Beach was an engineer working a bulldozer. He operated that machine as calmly as if clearing debris on a Saturday afternoon at home. Watching him gave me hope when all else seemed lost.”

Private Vinton Dove did not change the war.

But on June 6, 1944, for three violent hours under the worst fire of the Normandy landings—

he kept the invasion alive.

And that is enough.

News

My Family Missed My Wedding For My Sister, But My Castle Ceremony Changed Everything…..

My Family Missed My Wedding For My Sister, But My Castle Ceremony Changed Everything….. I was pinning my veil in…

The Germans mocked the Americans trapped in Bastogne, then General Patton said, Play the Ball

On a gray December morning in 1944, as snow fell over the forests of Belgium and Luxembourg, Allied commanders stared…

A 1912 Wedding Photo Looked Normal — Until They Zoomed In on the Bride’s Veil

On a quiet Saturday afternoon in downtown Chicago, Detective Rebecca Walsh walked into Murphy’s Antiques with one simple goal: find…

“Please Marry Me”, Billionaire Single Mom Begs A Homeless Man, What He Asked In Return Shocked…

The crowd outside the Super Save Supermarket stood frozen like mannequins. A Bentley Sleek had just pulled up on the…

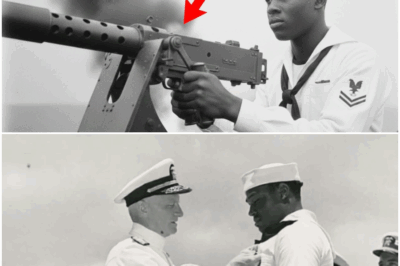

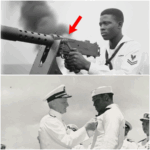

How One Black Cook’s “ILLEGAL” AA-Gun Grab Shook Pearl Harbor — And Forced the Navy to Change

On the morning of December 7, 1941, Pearl Harbor looked like a postcard. The water inside the harbor was calm…

She Was Serving Coffee in the Briefing Room — Then the Admiral Used Her Call Sign and the Room Froze….

She Was Serving Coffee in the Briefing Room — Then the Admiral Used Her Call Sign and the Room Froze…….

End of content

No more pages to load