**THE SNIPER IN THE CATTLE DOOR

Private James Ror and the Battlefield Innovation That Rewrote U.S. Army Doctrine**

At 2:15 p.m. on December 18, 1944, a cold wind skimmed across a Belgian farmstead as Private James Ror flattened himself against the dirt floor of a dark cattle barn. Snow filtered through gaps in the walls, dusted the aging timbers, and settled across the wooden stock he had pressed against his cheek. Outside, boots crunched through frozen underbrush—forty, perhaps fifty German infantrymen advancing through the Ardennes toward a farmhouse where a single American platoon braced for annihilation.

Ror’s finger hovered above the trigger of a modified Springfield rifle. His heartbeat slowed. The smell of manure and livestock rot pressed in around him. Everything about his firing position felt wrong—wrong by training, wrong by regulation, wrong by doctrine.

And precisely because it was wrong, it might save them.

He stared through a gap he had carved in the wall—four inches high, eight inches wide, just large enough to angle a rifle barrel through. The firing aperture sat eighteen inches above ground level. Any U.S. Army sniper instructor in 1944 would have called it useless. Manuals dictated firing from chest height—windows, balcony slits, sandbag nests, the places where generations of shooters had braced rifles at eye level.

But forty days of bloody combat in France and Belgium had taught Ror something the manuals hadn’t:

The Germans were hunting Americans at the heights Americans always used.

Nobody hunted at ankle level.

Over the next hour, from that cattle-door hide, Private James Ror would kill a dozen German soldiers, halt a company-sized advance, protect the flank of an isolated American unit, trigger a baffled German after-action report, survive a quiet Army investigation—and accidentally create a sniper tactic that would influence American doctrine for the next eighty years.

None of it was in the manual.

The Making of an Unlikely Innovator

Before he became a problem for the German 277th Volksgrenadier Division, Ror was a kid from Lawrenceville, one of Pittsburgh’s working-class river neighborhoods where men built steel and boys learned to work with their hands early.

His father labored at the blast furnaces of Jones & Laughlin Steel. His uncle owned a butcher shop on Butler Street. Those two environments—molten metal and clean cuts—shaped him.

In the mill, he learned precision: understanding heat, timing, force, the patience to watch molten iron reach the exact moment when theory met material reality.

In the butcher shop, he learned something else: efficiency of motion. How to remove a joint with a single decisive slice. How to carve quietly, cleanly, without waste. His uncle’s rule became his creed:

Clean cuts. No wasted motion. Do it right once.

On December 8, 1941—his 18th birthday—he enlisted. The Japanese bombed Pearl Harbor the day before; the war had come to America. He signed his name that afternoon. His father shook his hand. His mother packed lunches. His uncle gave him a knife he’d carved meat with for twenty years.

Fort Benning decided he should be a sniper.

He wasn’t flashy. Not a competition shooter. Not a natural marksman with instinctive brilliance. But he put bullets where they needed to go. Consistently. Coldly. Mechanically. He had what instructors called “practical accuracy”—the kind of reliability that keeps infantry alive.

They trained him for twelve weeks: wind calls, range estimation, fieldcraft, concealment, stalking, the technical calm of breathing control. But more importantly, they taught him the positions: windows, second-story floors, ground-level hides at chest or eye height. Standardized, predictable, uniform.

Normandy made those standards obsolete.

The Problem With Doing Everything “By the Book”

Ror came ashore on Omaha Beach with the 2nd Infantry Division. Through the bocage that summer, he learned what German snipers already knew: American snipers were dangerously predictable.

In August, he saw Private Danny Pierce—twenty years old—killed in a church steeple in Brest, a place U.S. manuals called “ideal elevation.” A German sniper needed only two shots.

In October, Corporal Frank Deets set up in a second-story warehouse window with perfect sight lines.

A German Panzerschreck team flattened the entire floor.

In November’s bitter fights in the Hürtgen Forest, Private Eugene Hayes took a prone position in a bunker firing slit. German machine gunners shredded the entire upper half of the structure before Hayes got off his fifth shot.

The Germans knew where Americans went.

Americans knew where Americans went.

Doctrine sent them all to the same places.

Ror began quietly violating doctrine—lowering his profile, shifting beneath standard positions, crawling into rubble piles instead of ruined windows. His officers chalked his idiosyncrasies up to caution. But he wasn’t cautious.

He was observing.

He was mapping American deaths.

He was seeing patterns instructors had missed.

He was trying to survive a war the manual wasn’t written for.

By mid-December, Ror had lost twenty-one friends.

When German armor and infantry surged through the Ardennes on December 16, 1944—beginning the Battle of the Bulge—he realized doctrine wasn’t just outdated.

It was deadly.

The Barn

The farmhouse east of Rocherath was small, isolated, and doomed unless someone slowed the German advance. Lieutenant Brennan, young and earnest and painfully inexperienced, studied his map and pointed at the barn northwest of the farmhouse.

“You’ll take position there,” he told Ror. “Pick officers. Slow them down.”

It was a “sniper’s dream” by the field manual definition: elevation, cover, good lanes of fire, structural concealment.

Ror had already scouted it.

He saw something different.

The barn’s windows were too large, too obvious, too perfect. The German counter-sniper who spotted a muzzle flash would kill him before his second shot. The doors were chest height—also obvious. The loft had sight lines but zero concealment.

But near the base of the north wall, beneath decades of weathering and cattle foul, he found a drainage gap—a place where manure and meltwater seeped out.

Crawling on his stomach, he pressed his cheek to the planks. Through the opening, he saw a thirty-degree arc toward the forest.

Low. Concealed. Unexpected.

He went to work.

At 1:30 a.m. on December 18, while the rest of the platoon slept, he used a saw and crowbar to widen the gap: four inches high became eight. He extended it several feet. Reinforced it so the structure wouldn’t collapse. When he slid the Springfield into position and settled flat on the cold dirt, he found something that made sense:

The sight picture was perfect.

He would fire from eighteen inches above the ground. From a cattle door. A place no manual authorized.

A place no German would expect.

The Shooting Begins

At 2:15 p.m., the Germans emerged: forty men pushing through the snow in disciplined formation. Their officer checked his map case at 180 yards.

Ror exhaled.

Squeezed.

The man fell.

The Germans went prone, rifles snapping up toward the farmhouse and upper barn windows. Their world existed between three and seven feet above the ground.

Nobody thought to check the base of the barn.

Ror’s bolt cycled.

He aimed at the squad leader.

Squeezed.

Second man down.

Machine-gun fire hammered the upper stories—useless. The cowshed stayed silent, invisible.

Ror began a rhythm: pick, fire, cycle—forcing the German formation to halt, then retreat, then reorganize.

Six minutes.

Nine confirmed kills.

Three probables.

Zero return fire on his actual location.

When the Germans attempted a second advance, he killed three more. When they tried mortars, the rounds struck the roof instead of the foundation-level gap. The concussion shook the barn, but the firing port remained intact.

By sundown, twelve Germans lay dead, four wounded, and a company halted by a lone private in a cattle shed.

Lieutenant Brennan went wide-eyed when he realized what had just happened.

“What did you do?” he asked.

Ror simply said:

“Slowed them down.”

The Germans Notice Something Is Wrong

The German company commander, Oberfeldwebel Herman Koer, was no amateur. A veteran of Poland, France, and the Eastern Front, he knew the signs of a competent sniper.

But nothing about this sniper fit the pattern.

His counter-sniper, Gefreiter Hans Lutter, could not find the shooter. No window flashes. No roofline angles. No logical hiding place.

Only one explanation made sense:

“He fires from below window height,” Lutter said reluctantly.

“Impossible,” Koer replied.

But after the mortars failed, the counter-sniper became convinced the Americans were employing a technique he had never seen—not in France, not in Russia, not in a decade of war.

His report filed three days later read, in part:

“American sniper utilizing non-standard foundation-level firing apertures.

Countermeasures unclear.”

It was one of the first German documents to describe the tactic that would later become U.S. Army standard.

And at that moment, only one American soldier was using it.

The Technique Spreads—Quietly

The next morning, Corporal Anthony Rizzo, the company’s other sniper, confronted Ror.

“How the hell did you do that?”

Ror led him to the cattle port.

Rizzo stared at the filthy, frozen gap.

“You lay in that?”

“They look too high,” Ror said simply.

Rizzo understood instantly.

By evening, he had shown a sniper in Baker Company. By December 20, four snipers were using foundation-level hides. By Christmas, seven across the regiment. None reported it formally. No one wrote it down.

It spread like all battlefield innovations: soldier to soldier, quietly, urgently, by men who wanted to live.

And German casualties spiked.

The Investigation

As the Bulge ground into January, V Corps intelligence began noticing an anomaly: unusually high German sniper and NCO casualties attributed to American sharpshooters—especially in engagements where Americans should have been out-positioned or suppressed.

Lieutenant Colonel Andrew Hardesty went to Rocherath himself.

He inspected the barn.

He crouched down and peered through Ror’s firing gap.

In one second, he understood both the tactical brilliance and the regulatory nightmare.

“You altered civilian structures,” Hardesty said.

“Yes, sir.”

“You violated sniper positioning doctrine.”

“Yes, sir.”

“You’ve taught others.”

“Yes, sir.”

Hardesty stepped outside with Lieutenant Brennan.

“We’re not filing charges,” he finally said. “But we’re not formalizing this yet. Let it spread quietly. The moment we make it doctrine, the Germans adapt.”

A memo was filed—classified, understated, influential:

“Recent frontline engagements demonstrate effectiveness of non-standard foundation-level firing positions. Recommend doctrinal review.”

But before that review happened, Victory in Europe arrived in May 1945.

Then came bureaucracy.

On May 3, military police found Ror in Bavaria. A Belgian farmer had filed a property damage claim for fifty dollars. The Army, consistent to a fault, launched a formal inquiry.

He faced a small panel—three officers who had spent the war behind desks.

“Private Ror, did you cut a hole in a barn wall without authorization?”

“Yes, sir.”

“Why?”

“To avoid dying, sir.”

They fined him fifty dollars.

That was the Army’s final official statement on his innovation.

After the War

Ror returned to Pittsburgh, resumed civilian life, and said nothing.

He worked blast furnaces for thirty-seven years. He married, raised three children, coached baseball, shoveled snow, paid taxes, and never once bragged.

His children didn’t know he’d been a sniper.

His wife learned only because she found his discharge papers.

He died in 1994 at age seventy-three. His obituary devoted one sentence to his war service.

No mention of innovation.

No mention of doctrine.

No mention of saving lives.

Rediscovery and Legacy

In 1998, historian Dr. Sarah Chen stumbled upon Hardesty’s memo while researching American sniper evolution. She followed the paper trail: after-action reports, battalion logs, German intelligence summaries, training bulletins from 1945.

Then she found Ror’s inquiry file—including the fifty-dollar fine.

Her 2001 book established what the Army never properly documented:

Foundation-level firing positions—now standard in U.S. sniper doctrine—originated with Private James Ror in December 1944.

The revelation rippled quietly through military circles.

In 2003, Fort Benning’s Sniper School added a short case study:

“Low-profile foundation hides: first observed in the Ardennes, 1944.”

No name attached.

But the math speaks for itself.

Studies estimate that the technique, once standardized, has saved hundreds of American snipers in conflicts from Korea to Iraq.

It is now ingrained so deeply into doctrine that few remember it was once heresy.

Snipers today learn the same principle Ror discovered alone in a freezing Belgian barn:

The enemy aims where they expect you to be.

So don’t be there.

A Legacy Without Glory

Ror never sought medals.

He never sought credit.

He never even told his children what he did.

But every American sniper who has ever slid into a cattle-door hide, a drainage channel, a rubble gap, a prone foundation slit—every shooter who has survived because they fought from a place the enemy never searched—has inherited his quiet brilliance.

History remembers generals, offensives, divisions.

But doctrine—real doctrine—often begins with a single cold soldier, lying on his belly in manure and frozen hay, deciding the manual is wrong.

James Ror did not think of himself as a hero.

He saw a problem.

He cut a hole.

He solved it.

And eighty years later, soldiers are still alive because he did.

That is a legacy worth remembering.

News

“Please Marry Me”, Billionaire Single Mom Begs A Homeless Man, What He Asked In Return Shocked…

The crowd outside the Super Save Supermarket stood frozen like mannequins. A Bentley Sleek had just pulled up on the…

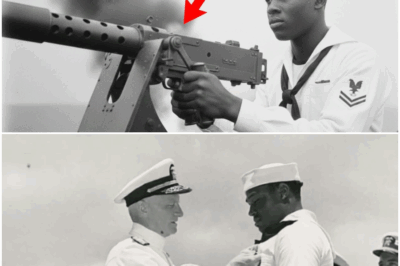

How One Black Cook’s “ILLEGAL” AA-Gun Grab Shook Pearl Harbor — And Forced the Navy to Change

On the morning of December 7, 1941, Pearl Harbor looked like a postcard. The water inside the harbor was calm…

She Was Serving Coffee in the Briefing Room — Then the Admiral Used Her Call Sign and the Room Froze….

She Was Serving Coffee in the Briefing Room — Then the Admiral Used Her Call Sign and the Room Froze…….

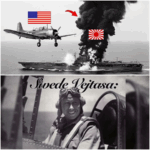

Japanese Couldn’t Hit This “Slow” Bomber — The Pilot Shot Down 3 Zeros and Sank Their Carrier

At 7:30 a.m. on May 8, 1942, Lieutenant (junior grade) Stanley “Swede” Vejtasa tightened his harness in the front cockpit…

At two in the morning, my phone buzzed with a message from my son: “Mom… I know you bought this house for ten million, but my mother-in-law doesn’t want you at the baby’s birthday.” I stared at the message for a long time. Finally, I responded: “I understand.” But that night, something inside me shifted. I knew I had put up with enough. I got up, opened the safe, and retrieved the set of documents I had kept hidden for three years. Then, I took the final step. By the time the sun rose… everyone was in shock—and my son was the most shocked of all…

At two o’clock in the morning, the blue glow of her phone dragged Helen Walker out of sleep. The room…

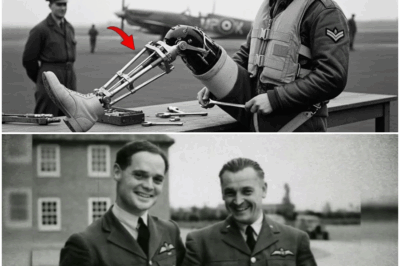

Germans Laughed at This ‘Legless Pilot’ — Until He Destroyed 21 of Their Fighters

At 7:45 on the morning of June 1, 1940, a Hawker Hurricane sliced through the thin coastal haze above Dunkirk….

End of content

No more pages to load