🇺🇸 The Weapon That Shouldn’t Exist: The Madman Mechanic and the Annihilation of the Bismarck Sea

Byline: The Historical Research Unit

Dateline: PORT MORESBY, Papua New Guinea – March 3, 2023 (80th Anniversary)

I. The Unbearable Sight: A Convoy’s Last Moments

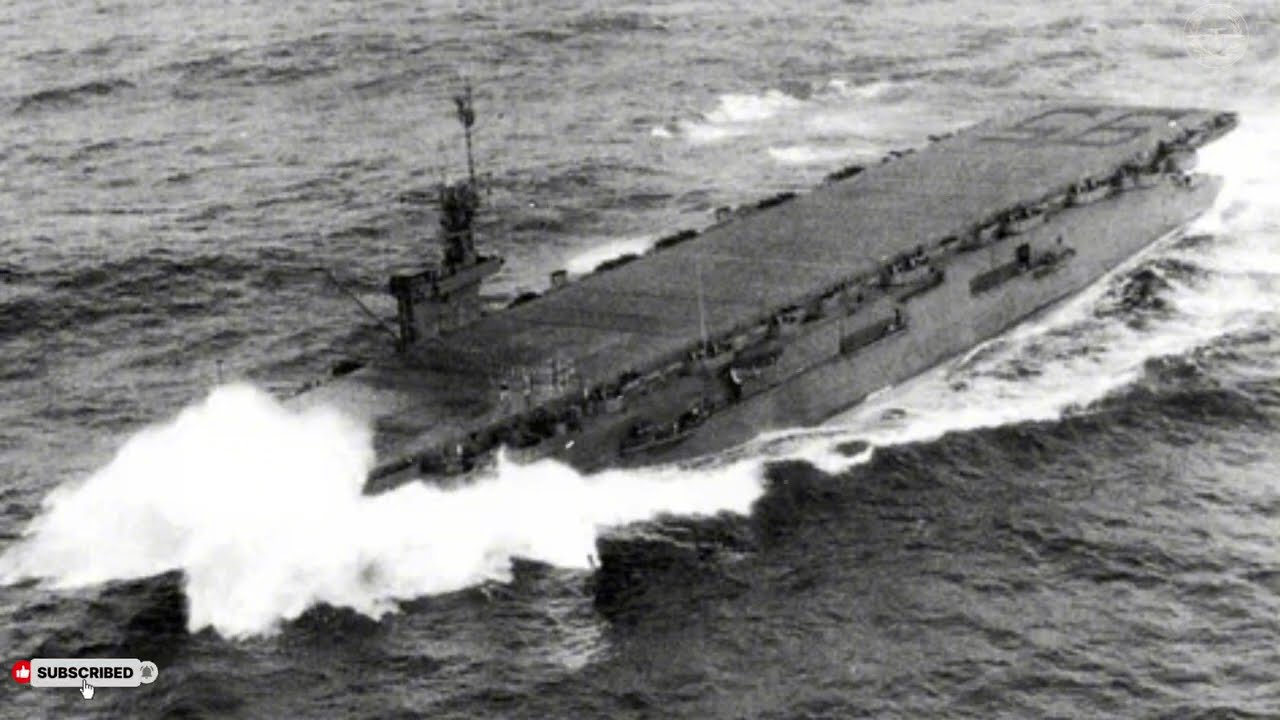

For the Japanese Imperial Navy, the transit through the Bismarck Sea was supposed to be routine. It was early March 1943. Eight troop transports, laden with nearly 7,000 soldiers destined to reinforce the besieged Japanese fortress in New Guinea, sliced confidently through the water, shielded by four modern destroyers. This convoy was the lifeblood of their Pacific defense—a conveyor belt of men and materiel. They were safe. The American bombers flew high, and their bombs always missed.

Then, the scream from a lookout sliced through the tropical morning air. He wasn’t pointing at the distant clouds where the B-17s usually lumbered. He was pointing straight ahead, at the water.

Approaching at terrifying speed, just fifty feet above the wave tops, were dark shadows that should not exist. They were American B-25 Mitchell bombers, but they were flying in a way that defied every known military doctrine—at mast height, at eye level. As they roared closer, their sleek, modified noses erupted, not with the flash of a single gun, but in a horrific, concentrated solid wall of white-hot tracers.

What followed was not a bombing run; it was, in the words of one surviving American pilot, “an execution.” In the span of fifteen minutes, the Japanese Imperial Navy watched in frozen horror as its entire force was annihilated. Eight transports and four destroyers—twelve ships—were ripped to pieces. Nearly 3,000 men were killed. This was not war; it was an act of erasure perpetrated by a weapon that, by all logic, history, and military doctrine, should have been impossible.

This is the untold story of that weapon and the grieving, obsessive mechanic who, fueled by a desperate need for revenge, broke every rule in the book to invent it.

II. The Problem in the Clouds: MacArthur’s Nightmare

By 1942, the war in the Pacific was an exercise in frustration for the Allies. While the fighting was brutal, the strategic reality was that the Japanese Empire was a fortress, its garrisons in New Guinea and elsewhere being steadily supplied.

General Douglas MacArthur, commanding the Allied forces in the Southwest Pacific, faced a strategic nightmare: his bomber fleet was useless against Japanese shipping.

The doctrine of high-altitude bombing—the B-17 Flying Fortress dropping bombs from 20,000 feet—was failing spectacularly. The bombs would fall for four long miles, giving Japanese captains ample time to turn the wheel, allowing the munitions to splash harmlessly into the ocean far behind them.

The Allied command was losing the war not through lack of courage, but through a failure of imagination and technology. They needed a new idea. They needed a weapon to solve the “ship-hitting problem.” But the solution would not come from a general in Washington D.C., or an engineer at a major aircraft corporation.

It came from a sixth-grade dropout from Arkansas, working in a dusty hangar in the Australian outback. His name was Paul “Pappy” Gunn.

III. The Mad Scientist of the Hangar: Pappy Gunn’s Vendetta

Pappy Gunn was not a strategist; he was a greased wizard, a master mechanic who had spent two decades flying and fixing Navy planes. Before the war, he had retired to the Philippines, where he built a small airline and raised a family: his wife, Polly, and four children.

When the Japanese invaded the Philippines, Pappy’s world was shattered. He was successfully evacuated to Australia to serve in the U.S. Army Air Forces as the Chief of Maintenance for the 3rd Bomb Group. But his family was captured and thrown into the brutal Santo Tomas internment camp.

For the generals, the conflict was a war of maps and supply lines. For Pappy Gunn, it was intensely personal—it was a rescue mission and a vendetta. While the high command debated doctrine, Pappy was staring at a photograph of his captive family. The only way to save them was to win the war, and the only way to win the war was to sink the ships feeding the Japanese machine.

Pappy became obsessed with one, singular, heretical idea: To sink ships, you had to get low. You had to fly at mast height and tear them apart with gunfire.

In an off-the-books, unsanctioned, and entirely illegal operation, Pappy and his trusted crew of mechanics began to modify the B-25 Mitchell medium bomber. They saw the B-25, a respectable, high-altitude aircraft, not as a bomber, but as a canvas for his grief and rage.

The Birth of the Strafer

Removing the Limits: They first ripped the glass nose and the bomb sight out of the aircraft. These symbols of the failed high-altitude doctrine were replaced with a solid, heavy steel plate.

Scavenging the Arsenal: Pappy began scavenging. He took .50 caliber machine guns—the standard anti-aircraft weapon—from wrecked fighters, discarded parts bins, and supply crates. He ignored requisitions and bypassed chains of command.

Bolting on the Fury: He began bolting the guns directly into the new solid nose. First, there were four guns, then six. Pappy, in his relentless pursuit of concentrated firepower, finally settled on eight forward-firing .50 caliber machine guns mounted in the nose section. This was in addition to the two flexible guns in the standard top turret.

The Monster is Born: Pappy had created a monster: a medium bomber with the nose firepower equivalent to three heavy fighters. When the pilot hit the trigger, all eight guns fired at once, unleashing a two-second burst that delivered over 100 pounds of lead into the target. It didn’t fire bullets; it fired a solid wall of steel. The sound alone was a physical roar—a tearing force. The B-25 had become the B-25 Strafer, the most terrifying ship killer of the war.

IV. The Heresy of Skip Bombing

The Strafer, however, was only half the solution. The other half was a tactic so reckless and heretical that it defied every rule of air warfare. It was called Skip Bombing.

The traditional methods of attacking ships were flawed:

Torpedoes: Required slow, vulnerable torpedo bombers, making them easy targets for anti-aircraft guns.

High-Altitude Bombs: Were tragically inaccurate, as MacArthur had learned.

Pappy’s solution was to turn the conventional 500-pound bomb into a high-speed, lethal cannonball. The tactic was designed as a choreographed, two-step knockout:

The Sweep: The B-25 Strafer would scream in at 50 feet—low enough to be invisible to radar until the last moment. Its eight nose guns would blaze, sweeping the Japanese anti-aircraft gunners from their decks and rendering the enemy defenses useless.

The Skip: Then, just 300 yards from the target, the pilot would release a 500-pound bomb fitted with a five-second delay fuse. The bomb would hit the water, skip once or twice like a flat stone skipping across a lake, and slam straight into the ship’s hull at the waterline, where the armor was thinnest. It would punch through the hull, and then, five seconds later, explode deep inside the ship’s engine room or fuel bunkers.

The Japanese had no counter for this. Their anti-aircraft guns were designed to shoot up at high-flying planes, not depress down low enough to defend against a wave-skimming aircraft. The combination of the Strafer’s unprecedented firepower and the Skip Bombing’s low-altitude, hull-breaching lethality created a weapon system the Japanese simply could not survive.

V. March 3, 1943: The Massacre in the Sea

The Japanese convoy, sailing through the Bismarck Sea on March 3rd, 1943, was arrogant, confident in its defensive destroyers and the proven ineffectiveness of American bombers. It was a routine, safe run.

At 10:15 a.m., the dark shapes appeared on the horizon. The lookouts watched in astonishment as they dropped lower and lower, until they were flying at water level. The Japanese captains were in a state of shock—This is impossible. This isn’t in the manual.

Then, the sky exploded.

The First Wave: The Execution

The initial wave of B-25 Strafers hit the convoy with a physical, tearing roar. The sound of over 100 heavy machine guns firing simultaneously was overwhelming.

The Japanese anti-aircraft gunners, unable to depress their barrels low enough, were shredded at their posts before they could even understand the nature of the attack.

The decks of the destroyers became a slaughterhouse, the wall of tracers ripping through steel and flesh.

Through this hail of lead, the B-25s maintained their course, releasing their bombs at the 300-yard mark.

A Japanese captain on the transport Oigawa Maru watched in paralyzed horror as a 500-pound bomb skipped perfectly across the water, impacted his hull, and vanished. Five seconds later, the entire ship erupted from the inside out.

The Annihilation

The convoy scattered in a panic, captains turning their ships into one another in a futile attempt to avoid the low-flying wolves. The B-25s, joined by Australian Beaufighters armed with cannons, attacked relentlessly.

One transport, filled with aviation fuel, was struck. It didn’t sink—it vaporized in a fireball that rose five hundred feet, the heat felt by pilots a mile away.

Another transport, hit by two skip bombs, buckled and broke in half. The 7,000 soldiers meant to reinforce New Guinea were now jumping into a sea of burning oil and churning wreckage.

In a final, brutal sweep, the destroyers were hit. Their thin hulls were no match for the combined force of the skip bombs and the continuous, concentrated .50 caliber fire.

In just 15 minutes, the battle was over. The pride of the convoy was gone. Eight transports and four destroyers were burning or sinking. The sea was black with smoke and red with blood. Nearly 3,000 Imperial Japanese servicemen were dead.

VI. The Turning Point

When news of the Battle of the Bismarck Sea reached Tokyo, the High Command was stunned into silence. It was not just the profound loss of men and ships; it was the way they were lost—the speed, the totality, the counter-less nature of the attack. They had been defeated by a weapon and a tactic they never conceived of.

The Battle of the Bismarck Sea proved to be the decisive turning point in the New Guinea campaign. The supply line was permanently severed. The Japanese never again attempted to send a major convoy to reinforce their positions. Isolated garrisons, starved of food and ammunition, were left to wither on the vine. The back of the Japanese Pacific fortress was broken.

And it was broken by Pappy Gunn.

The mechanic fueled by grief had accomplished what the entire U.S. high command could not. His illegal, off-the-books field modification—the B-25 Strafer—immediately became standard issue across the U.S. Army Air Forces. His heretical tactic—Skip Bombing—became the new doctrine for anti-shipping operations.

Pappy Gunn had fixed a failing war.

VII. The Mechanic Who Fixed the World

Paul “Pappy” Gunn continued his service, a legend among his mechanics and pilots. He became a crucial figure in the air war, his ingenuity saving countless American lives.

When he was finally reunited with his wife and four children after the war, his son, curious about his father’s heroic wartime efforts, asked him what he did during the conflict.

Pappy Gunn, the man who designed a weapon of annihilation, who created a new doctrine, and who broke the Japanese supply chain, simply replied that he was a mechanic who fixed a problem.

His story is a powerful reminder that sometimes, the most revolutionary ideas—the ones that change the course of history—do not emerge from the polished boardrooms of Washington D.C., but from the grit and grease of the hangar floor. They come from a grieving heart, from a focused rage, and from a man with nothing left to lose and a desperate need to survive.

Final Tally: The Battle of the Bismarck Sea marked the end of the Japanese ability to supply New Guinea. The sheer lethality and speed of the B-25 Strafer and Skip Bombing technique proved that ingenuity and vengeance, when combined, could defeat doctrine and superior numbers. The mechanic had won the battle the strategists could not.

Would you like me to research and provide a technical breakdown of the B-25 Strafer’s modifications, including how the added weight affected the aircraft’s performance?

News

This B-17 Gunner Fell 4 Miles With No Parachute — And Kept Shooting at German Fighters

The Day the B-17 Broke At 11:47 a.m. on November 29th, 1943, the sky above Bremen, Germany, was a…

They Mocked This Barber’s Sniper Training — Until He Killed 30 Germans in Just Days

On the morning of June 6, 1944, at 9:12 a.m., Marine Derek Cakebread stepped off a British landing craft into…

They Mocked His ‘Mail-Order’ Rifle — Until He Killed 11 Japanese Snipers in 4 Days

🎯 The Unconventional Weapon: How John George’s Civilian Rifle Broke the Guadalcanal Sniper Siege Second Lieutenant John George’s actions…

” We All Will Marry You” Said 128 Female German POWs To One Farm Boy | Fictional War Story

The Marriage Petition: The Nebraska Farm Boy Who Saved an Army of Women With a Choice, Not a Shot …

“German Mothers Wept When American Soldiers Carried Their Babies to Safety in WW2”

The Unplanned Truce: How Compassion Crumbled the Propaganda Wall Near Aken, 1944 In the Freezing Ruins of Germany, American…

Japanese Female Nurses Captured SHOCKED _ When U.S Doctors Ask for their help in Surgery

The Unbroken Oath: How Japanese Nurses Shattered Propaganda By Saving American Lives in a Field Hospital in 1945 Behind…

End of content

No more pages to load