On a gray December morning in 1944, as snow fell over the forests of Belgium and Luxembourg, Allied commanders stared at their maps in disbelief.

German arrows were pushing westward where, according to every plan and every intelligence estimate, there shouldn’t have been any serious German attack at all. What had seemed like a quiet sector—manned largely by green American divisions “resting” after earlier fighting—was exploding into chaos.

Where there had been a thin American line, there was now a bulge.

Some German officers boasted that this would be their second “Dunkirk,” the moment when they smashed the Western Allies and forced them to the bargaining table. They were aiming for Antwerp, the vital port that kept the Allied armies fed, fueled, and armed. If they reached it, they might split the British and American forces and prolong the war for years.

Many in the German high command were certain they’d pulled off the impossible: total surprise against the Americans.

What they didn’t count on was a 59-year-old American general already thinking two moves ahead: George S. Patton, Jr.

Within days, his Third Army would perform one of the most extraordinary pivots in modern military history, turn straight into the worst winter Europe had seen in decades, and slam into the German flank so hard that Hitler’s last great gamble in the West never recovered.

This is the story of how Patton helped turn the Battle of the Bulge from a looming Allied disaster into what Winston Churchill later called “the greatest American battle of the war.”

The Situation in December 1944: “The War Is Almost Over”… Until It Isn’t

By early December 1944, many Allied soldiers believed the war in Europe was nearly won.

Paris had been liberated in August. American and British forces had pushed the Germans back across France and Belgium. The Soviet Red Army was crushing German divisions in the East. There was talk in mess halls that the troops might be home by spring—maybe even earlier, if Germany finally collapsed.

On paper, that optimism had some justification. Germany’s fuel supplies were depleted, its Luftwaffe air force was a shadow of its former self, and Allied bombers were pounding its cities and factories.

But Adolf Hitler saw things differently.

He believed that if Germany could land just one more heavy blow in the West—something that shocked the Allies, drove a wedge between the Americans and British, and took the crucial port of Antwerp—the Western powers might be willing to negotiate. Maybe not a full peace, but a stalemate that would allow him to focus on the Soviets and preserve something of his empire.

To accomplish that, he planned Operation Wacht am Rhein (“Watch on the Rhine”), soon to be known simply as the Ardennes Offensive—or, to most Americans, the Battle of the Bulge.

The plan was audacious, bordering on insane.

Hitler wanted three German armies—around 250,000 troops and nearly 1,000 tanks and assault guns—to smash through a 60-mile front in the Ardennes Forest, drive west through Belgium, cross the Meuse River, and seize Antwerp. He had maybe six days’ worth of fuel for this operation. After that, his tanks would have to capture Allied fuel dumps or stop cold.

It was all or nothing.

The German Attack: Total Surprise in the Snow

At 5:30 a.m. on December 16, 1944, German artillery opened up along a 130-mile front in the Ardennes. Moments later, infantry and tanks began pushing through the mist and trees.

The Ardennes region—rough, hilly, forested—was exactly where Allied planners thought the Germans were least likely to attack. It had been considered a “quiet sector.” American divisions there included the 99th and 106th Infantry Divisions, many of whose soldiers were new to combat.

Allied intelligence had missed the signs of what was coming. The Germans had moved their troops and tanks at night, under strict radio silence. They used deceptive radio traffic elsewhere to confuse Allied eavesdroppers. The weather—low clouds, snow, and fog—kept Allied reconnaissance planes grounded.

The result was shock.

In the first days of the offensive, German armored units tore into thin American lines, overwhelmed forward positions, and punched westward. In some places, proud U.S. units were overrun. Others were forced to retreat in confusion. There were heroic stands—like the 99th Division’s defense near Elsenborn Ridge—but overall, the Germans achieved exactly what they’d hoped for: a giant hole in the Allied front, a bulge pushing 20 miles deep into Belgium.

In the chaotic first days, some Allied commanders feared the worst. The 106th Division lost thousands of men in mass surrenders. German troops in American uniforms caused confusion behind the lines. Fuel depots were threatened. The road to the Meuse River suddenly looked open.

And in the middle of all this, in the city of Verdun, General Dwight D. Eisenhower, Supreme Commander of Allied forces in Europe, summoned his top field commanders for an emergency conference on December 19.

Enter Patton: “I Can Attack with Three Divisions in 48 Hours”

George S. Patton, Jr. walked into that conference already thinking about the next move.

At 59, the silver-helmeted, pearl-handled-revolver-wearing commander of the U.S. Third Army was already a legend. He had led the first American tank units in World War I, commanded armored forces in North Africa and Sicily in World War II, and—after nearly losing his career over the infamous “slapping incidents”—had redeemed himself spectacularly in France.

His Third Army’s dash across France in the summer of 1944 had been astonishing: 600 miles in 4 months, thousands of square miles liberated, hundreds of thousands of German troops captured. His style was aggressively offensive. In his view, the best way to win a war was to attack relentlessly and keep the enemy too busy defending to organize a counterstrike.

Patton’s personality was larger than life—profane, theatrical, sometimes offensive, deeply religious in his own way, and absolutely convinced that he was born to be a great commander. He carried volumes of military history in his head and frequently compared his campaigns to those of Alexander the Great, Napoleon, and Caesar.

But what mattered in December 1944 wasn’t his ego.

It was his preparation.

In the days leading up to the German attack, Patton’s intelligence staff had noticed troubling signs: increased German traffic on some roads, strange radio patterns, rumors of new units appearing opposite their front. While higher-level Allied intelligence discounted these hints, Patton’s staff quietly drafted three contingency plans for what Third Army would do if the Germans launched a major attack in the Ardennes.

All three plans involved turning his army north.

At Verdun, when Eisenhower asked how quickly Third Army could pivot and counterattack, other commanders thought such a move would take a week or more.

Patton said something that made them think he was either lying or crazy:

“I can attack with three divisions in 48 hours.”

Eisenhower was so shocked he asked him to repeat it.

Patton repeated it—and meant it.

He already knew which divisions he would pull out of the line, which roads they would take, and where they would go. All he needed to do was give the codeword to his headquarters.

Ike didn’t have many options. The British field marshal Bernard Montgomery commanded the northern sector. Patton’s Third Army was in the south. Right now, in the center—the Ardennes—there was a gaping hole. If Patton could, in fact, turn north that fast, he might not only relieve threatened positions like the crossroads town of Bastogne, but also slam into the German flank and stall their offensive.

Eisenhower told Patton to do it.

The meeting ended. Patton walked out, found a phone, and uttered the prearranged code to his staff:

“Play ball.”

Within hours, one of the most complex troop movements of the war was under way.

The Impossible Pivot: Six Divisions, Winter Roads, 72 Hours

It’s hard, from the comfort of a warm living room, to appreciate what Patton was asking his soldiers to do.

The Third Army was not sitting idle. It was already engaged in heavy fighting in the Saar region along Germany’s border. Patton now had to pull six divisions out of active combat, pivot them 90 degrees, and march them more than 100 miles through snow-covered, icy roads toward the Ardennes—all while maintaining enough discipline that they could arrive ready to fight immediately.

Military textbooks say that moving an army in contact with the enemy is one of the hardest maneuvers there is. Doing it in the middle of a brutal winter, on short notice, with traffic control challenges and limited fuel? Nearly impossible.

Third Army did it anyway.

In the days that followed, over 130,000 vehicles—trucks, jeeps, tanks, halftracks, artillery pieces—began moving north. Among them were key combat units:

4th Armored Division

26th Infantry Division

80th Infantry Division

and others designated to support and reinforce.

They rolled day and night over narrow, icy roads, headlights blacked out or dimmed because of blackout rules, drivers leaning forward in the freezing dark. Mechanics fought constantly to keep engines running; motor oil thickened in the cold, and vehicles had to be started regularly to avoid freezing.

The weather was vicious. December 1944 brought some of the coldest temperatures Europe had seen in decades. Snow piled up. Soldiers lacked proper winter gear—many had thin field jackets and regular leather boots, not the insulated clothing they would get later in the war. Frostbite cases mounted.

Yet in truck cabs and along the sides of frozen roads, a rumor started to spread:

“Old Blood and Guts is heading north.”

Patton, as was his habit, made himself visible. He toured columns in his open jeep, wrapped in a greatcoat, helmet on his head, watching his men slog through the misery.

He was quoted as telling one unit:

“No b——d ever won a war by dying for his country. He won it by making the other poor dumb b——d die for his.”

Crude? Absolutely. Motivating? Also yes.

His presence told his soldiers that if he expected them to drive into hell, he’d at least be seen near the gate.

The Siege of Bastogne and the Plan to Relieve It

While Patton’s men were grinding north, another group of Americans was making a stand that would become legendary.

The town of Bastogne, a road hub in southern Belgium, sat in the middle of the German advance. Seven major roads converged there. Whoever held it had a huge advantage in moving troops and supplies.

As the German spearheads pushed west, Bastogne quickly became a target.

The U.S. 101st Airborne Division—the “Screaming Eagles”—along with elements of other units, was rushed into the town and quickly surrounded. The weather was too bad for regular air resupply or bombardment. German forces, including armor, encircled the area and began squeezing.

On December 22, German envoys approached with a white flag and a written demand for surrender. They warned that if the Americans didn’t lay down their arms, they would be “annihilated.”

Acting division commander Brigadier General Anthony McAuliffe read the message, laughed, and scribbled a one-word reply:

“NUTS!”

When the Germans asked what that meant, the American officer delivering the reply translated it as, “In plain English? Go to hell.”

That defiance became a rallying cry—but defiance alone wouldn’t break the encirclement.

That was Patton’s job.

From the start, he’d seen Bastogne as the key. If he could punch a corridor through to the town, he would not only save the troops trapped there but also threaten the entire German advance. The bulge in the American line would suddenly have a strong, angry fist hitting it from the south.

Patton’s attack plan called for three divisions to push north toward Bastogne on a roughly 20-mile front. The 4th Armored Division would spearhead the drive straight for the town, with infantry divisions securing the flanks.

The catch? He had to do it in the middle of a blizzard, over frozen, forested ground the enemy assumed no major offensive could cross.

“Grant Us Fair Weather for Battle”

There’s a famous story from this phase of the campaign, one that says a lot about Patton’s mix of showmanship, faith, and understanding of morale.

Frustrated by the constant snow and low clouds that grounded Allied aircraft, he called in his chaplain, Colonel James O’Neill, and ordered him to write a prayer for good weather.

“Chaplain,” Patton said, “I want you to get me some good weather. I’m tired of these clouds. I’m tired of this rain. I’m tired of this mud.”

O’Neill protested that prayer wasn’t exactly a weather control device, but Patton insisted. The chaplain drafted a short prayer:

“Almighty and most merciful Father, we humbly beseech Thee, of Thy great goodness, to restrain these immoderate rains with which we have had to contend. Grant us fair weather for battle…”

Patton liked it so much he had the prayer printed on cards—about 250,000 of them—with his own Christmas greeting on the reverse. These were distributed throughout Third Army.

Two days later, on December 23, the clouds broke.

The skies cleared.

And Allied fighter-bombers roared into action.

Was it a miracle? A coincidence? Luck? Meteorology eventually would have cleared the front anyway.

Whatever you believe, the effect was unmistakable: once the weather opened up, American and British aircraft began hammering German columns, pummeling their vehicles, and interdicting their already overstretched supply lines.

Patton got his “fair weather for battle.”

He used it.

The Drive to Bastogne: “This Time the Kraut Stuck His Head in the Meat Grinder”

On December 22, Patton’s forces began their offensive northward. The initial attacks met stiff resistance. German units, including elements of crack Panzer divisions, had not expected such a rapid response but recovered quickly enough to fight hard. Snow and ice turned roads into skating rinks. Vehicles slid into ditches. Infantry slogged through knee-deep drifts.

Yet day by day, mile by mile, Third Army pushed.

The 4th Armored Division in particular drove like a battering ram. Its tankers fought German Panthers and Tigers in fields and forests, trading steel and blood for yards of snow-covered ground.

Patton’s orders were clear and uncompromising: keep attacking.

He understood that the German offensive depended on momentum. If he could keep hammering their flank, they would be forced to divert units away from their push toward the Meuse and Antwerp, buying time for other Allied forces to stabilize the northern shoulder.

There’s a famous quote attributed to Patton in a conversation with his superior, General Omar Bradley, around this time:

“Brad, this time the Kraut has stuck his head in the meat grinder, and I’ve got hold of the handle.”

Crude again—but accurate.

The German spearhead had overextended itself. Fuel was running low. Some units were already siphoning gas from abandoned vehicles. Patton’s men, hitting from the south, were like a wrench shoved into the gears of a machine already grinding itself apart.

Christmas in Bastogne: The Link-Up

By Christmas Day, December 25, the men of the 101st Airborne in Bastogne had been fighting surrounded for days. They were exhausted, low on supplies, and freezing—but still holding.

Just after dark on December 26, tanks of C Company, 37th Tank Battalion, 4th Armored Division—part of Patton’s Third Army—rumbled into the southern outskirts of the town.

The lead tank commander, Lt. Charles Boggess, stopped at a crossroad where surprised paratroopers emerged from foxholes and cellar doors to greet them.

The gap they’d opened was narrow, barely a few hundred yards wide, and still under fire. But it was enough. Bastogne was no longer cut off.

The relief of Bastogne wasn’t the end of the Battle of the Bulge, but it was the turning point. The psychological impact was enormous. For the Germans, the failure to take the crossroads town quickly and crush the U.S. forces there signaled that their offensive timetable was wrecked. For the Americans, it was proof that they could fight through the worst the enemy and the weather could throw at them.

From that point on, the question was not whether the German offensive would succeed, but how quickly the Allies could pinch off the bulge and force the enemy back.

The Long Squeeze: From Bulge to Collapse

The fighting in the Ardennes did not end quickly. January 1945 was a month of savage, grinding combat as American forces from the north (including British units under Montgomery) and Patton’s forces from the south fought to reduce the bulge.

Conditions remained brutal. Soldiers on both sides suffered frostbite, trench foot, and exhaustion. Artillery pounded frozen ground. Trees shattered under shell blasts, sending deadly splinters—“tree bursts”—through open air. Villages changed hands multiple times.

By mid-January, however, it was clear the Germans had shot their bolt.

On January 16, 1945, elements of Patton’s Third Army linked up with units of the U.S. First Army at the town of Houffalize, effectively closing the base of the bulge. The German forces that had driven west were now either retreating in disorder or being cut off and destroyed.

The statistics tell the story:

German casualties: roughly 100,000 killed, wounded, or captured.

German tanks and assault guns lost: more than 700.

German aircraft destroyed: over 1,600.

American casualties: around 80,000 (killed, wounded, missing)—the costliest U.S. battle of the war.

But from Hitler’s perspective, the more important number was this: he had no more strategic reserves.

He had gambled everything he could spare in the West on the Ardennes offensive—and lost.

From February 1945 onward, the German army in the West was in permanent retreat.

Patton’s Role: More Than “Old Blood and Guts”

It’s easy, decades later, to reduce Patton’s involvement at the Bulge to a few caricatured images: the flamboyant general in his polished helmet, the gruff one-liners, the famous prayer for weather.

But his contribution went far beyond showmanship.

He did three things that were absolutely critical:

He anticipated the possibility of a German counterattack in the Ardennes and had contingency plans ready when others didn’t.

He executed a massive, rapid pivot of his army under combat conditions—something most military planners would have considered impossible—bringing fresh, aggressive forces to bear on the German flank within days rather than weeks.

He kept his soldiers’ morale and momentum high in horrific conditions, making them believe that they could, and would, win.

German generals later admitted that they’d underestimated him.

General Gerd von Rundstedt, the German commander in the West, reportedly considered Patton the Allies’ most dangerous field commander. General Günther Blumentritt, another senior German officer, later wrote:

“We regarded General Patton extremely highly as the most aggressive tank general of the Allies. His operations impressed us enormously, because he came closest to our own concept of the classical military commander.”

Coming from men who had served under the likes of Manstein and Guderian, that was no small compliment.

For Patton himself, the Battle of the Bulge was a vindication. Earlier in the war, critics had whispered that he was good at chasing a beaten enemy but might falter against a determined foe. In the Ardennes, he proved he could handle both: defense, rapid maneuver, and offense under pressure.

He understood that wars aren’t won by cautious perfection.

They’re won by bold moves, taken at the right moment, by leaders willing to bet their reputations on the courage and toughness of their troops.

“The Greatest American Battle of the War”

When the story of the Battle of the Bulge is told, rightly, the spotlight often shines on the 101st Airborne at Bastogne, on the artillerymen who fired until their barrels glowed, on the infantry who froze in foxholes and fought in villages like St. Vith and Foy.

George Patton would have agreed with that emphasis. He never stopped reminding people that soldiers, not generals, win battles.

But without his Third Army’s pivot north, their sacrifices might have become part of a tragic, losing story instead of a hard-fought victory.

Winston Churchill, who was famously stingy with praise for Allied operations that didn’t involve the British, told Parliament in January 1945:

“This is undoubtedly the greatest American battle of the war…”

He meant the entire Bulge campaign.

Patton’s role in that “greatest battle” was essential.

In a war full of enormous numbers—millions of men, tens of thousands of tanks and planes—it’s easy to forget how much difference the judgment of a single commander at a single meeting can make.

On December 19, 1944, in a cold room in Verdun, when it looked like Hitler’s surprise offensive might break the Allied front wide open, Eisenhower asked:

“How soon can you turn your army and counterattack to the north?”

George Patton didn’t say, “I’ll need a week to figure it out.”

He said:

“I can attack with three divisions in 48 hours.”

Then he went out and did it.

In the frozen forests and snow-covered fields of the Ardennes, where the snow turned crimson with blood, the Third Army’s tracks and bootprints mark more than just movement on a map.

They mark the moment when Hitler’s last hope in the West ran into American willpower, American improvisation, and an American general who believed that, no matter how bad the situation looked, the right answer was still:

News

My Family Missed My Wedding For My Sister, But My Castle Ceremony Changed Everything…..

My Family Missed My Wedding For My Sister, But My Castle Ceremony Changed Everything….. I was pinning my veil in…

A 1912 Wedding Photo Looked Normal — Until They Zoomed In on the Bride’s Veil

On a quiet Saturday afternoon in downtown Chicago, Detective Rebecca Walsh walked into Murphy’s Antiques with one simple goal: find…

“Please Marry Me”, Billionaire Single Mom Begs A Homeless Man, What He Asked In Return Shocked…

The crowd outside the Super Save Supermarket stood frozen like mannequins. A Bentley Sleek had just pulled up on the…

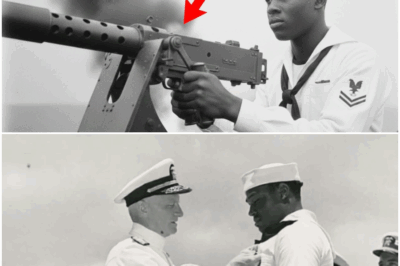

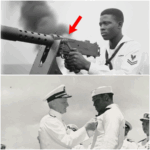

How One Black Cook’s “ILLEGAL” AA-Gun Grab Shook Pearl Harbor — And Forced the Navy to Change

On the morning of December 7, 1941, Pearl Harbor looked like a postcard. The water inside the harbor was calm…

She Was Serving Coffee in the Briefing Room — Then the Admiral Used Her Call Sign and the Room Froze….

She Was Serving Coffee in the Briefing Room — Then the Admiral Used Her Call Sign and the Room Froze…….

Japanese Couldn’t Hit This “Slow” Bomber — The Pilot Shot Down 3 Zeros and Sank Their Carrier

At 7:30 a.m. on May 8, 1942, Lieutenant (junior grade) Stanley “Swede” Vejtasa tightened his harness in the front cockpit…

End of content

No more pages to load