Into the Teeth of Hell: Major Raymond Wilkins, Bloody Tuesday, and the American Spirit in War

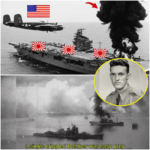

On the morning of November 2, 1943, a 26-year-old bomber pilot named Raymond Harold Wilkins climbed into the cockpit of his B-25 Mitchell and flew straight toward what many believed was the most heavily defended target in the Pacific.

He was tired. He was on his 87th combat mission. Everyone he had come to war with in the original Third Bombardment Group was dead, missing, or sent home. And yet, as the sun rose over the Solomon Sea, he led eight B-25s toward Rabaul—a fortress ringed by 367 anti-aircraft guns and nearly 400 Japanese fighters.

By the end of that day, 45 American airmen would be dead or missing. But the Marines fighting for a foothold on Bougainville would still be alive. Japanese cruisers and destroyers would remain in harbor, unable to disrupt the invasion. And Major Wilkins would never come home.

What he did in between—over Simpson Harbor, at mast-height, under a storm of steel—is one of those stories that shows, in stark, painful clarity, what kind of people wear the American uniform and what they’re willing to give up for one another.

A Quiet Briefing and a Brutal Mission

Three hours before takeoff, in a briefing room in New Guinea, the mood was quiet. Crews of the Fifth Air Force sat listening to intelligence officers outline the target: Simpson Harbor at Rabaul, the main Japanese stronghold in the Southwest Pacific.

Rabaul wasn’t just another dot on a map. It was the “Pearl Harbor of the South Pacific”—a deep, protected anchorage ringed by volcanic peaks and bristling with guns. Inside that harbor lay cruisers and destroyers that could steam out and hammer the Marines who had landed on Bougainville two days earlier.

If those ships sailed, the invasion could fail. If they were kept in port—or sunk—the Marines would have a chance.

The plan was simple and savage:

Approach at mast-head level, only 50–100 feet above the water.

Skip-bomb the anchored ships—release 500-pound bombs at low altitude, let them bounce across the surface, and slam into hulls below the waterline.

Use eight .50-caliber machine guns firing straight ahead to sweep decks and silence gun crews during the run.

Get out before the sky filled with Japanese fighters.

The briefing officer’s prediction was blunt: not all of them would be coming home.

Wilkins knew exactly what that meant. He had arrived in theater in early 1942 with dozens of crews. Twenty months later, almost all of those men were gone—burned over New Guinea, ditched into the Coral Sea, vanished during long-range missions that never reported back.

He was the last man still flying combat from that original group.

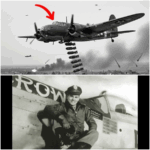

He tightened the chin strap on his helmet, walked out to his aircraft—B-25 “Fifi”—and led eight bombers toward the toughest target in the theater.

A New Way to Fight a Deadly War

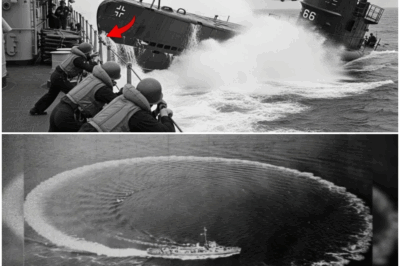

The B-25s Wilkins led that day were not the same aircraft that had arrived in the Pacific in 1942.

Standard B-25s, with glass noses and bomb bays built for medium-altitude bombing, had proven dangerously vulnerable when they tried to attack ships at low level. Japanese anti-aircraft fire shredded them. Bombing accuracy at higher altitudes wasn’t good enough to guarantee hits on maneuvering warships.

So the men of the Fifth Air Force did what Americans have done in every war: they adapted.

At places like Eagle Farm Airfield in Brisbane, mechanics and engineers tore the noses open and rebuilt them. Bombardiers’ positions and delicate glass panes were removed. In their place, they mounted firepower:

Four .50-caliber machine guns fixed in the nose

Four more in pods mounted on the fuselage sides

Eight heavy machine guns all pointing forward, capable of hurling hundreds of rounds per second into a target.

This wasn’t in a manual. This wasn’t something an engineer in a stateside office dreamed up. It was born out of trial and error—mostly error—over the Jungles and seas of the Southwest Pacific. Crews flew in, tried new tactics, and often never came back to talk about what worked.

The survivors learned to approach below radar, skim the wave tops, and line up on ships at ranges so close that every second counted. They learned to trust their gunners to clear decks with fire while they skimmed a few feet above the water, leveled off, released their bombs, and yanked their aircraft away from the blast.

It was dangerous. It was brutal. And it worked.

Wilkins had been there for the entire evolution. Many of the men who helped perfect low-level, skip-bombing attacks were already dead by the time he flew into Rabaul. He carried their lessons—and their ghosts—with him into that harbor.

“Mast-Head Height”: The Run into Simpson Harbor

As his formation crossed the Solomon Sea, the call came down from Japanese radar: incoming bombers.

Down below, at Rabaul, fighter groups from five airfields began to scramble—units from land bases and carrier air groups that had been moved ashore. Anti-aircraft batteries manned their guns. On the ridgelines and around the harbor, 367 gun positions waited.

The crews of the B-25s didn’t see any of that yet. They saw water, sky, and the thick jungle coastline coming up fast. As the harbor entrance opened ahead, Wilkins dropped to around 100 feet. Salt spray hit the windscreen. The eight aircraft tightened formation and roared into Simpson Harbor.

The scene ahead looked like a target range and death trap combined: cruisers, destroyers, transports—all the ships Fifth Air Force had hoped to find, all of them bristling with weapons.

Then the first heavy gun spoke. A shell burst 200 yards in front of Wilkins’s nose, black smoke marking the air. More guns joined in. The sky ahead became a latticework of tracer and bursting shells.

Wilkins did what he’d trained himself to do: he pushed the throttles forward and dropped even lower—down to perhaps 70 feet—riding a line between the ocean and the storm of fire ahead.

At 500 yards from a Japanese destroyer, he squeezed the trigger.

Eight .50-calibers stitched a glowing path toward the ship. Tracers ripped across the destroyer’s deck, chewing through steel and flesh. Gun crews fell, positions erupted, men dove for cover where there was none.

At 300 yards, the enemy gunners fired back in earnest—20 mm shells from close-range mounts, heavier fire from shore batteries. The B-25 shuddered as rounds tore through wings and fuselage. But Wilkins held the line.

At around 200 yards, bombs dropped free—two 500-pounders skipping across the water like stones skimming a pond.

One slammed into the destroyer near the engine room, below the waterline. The other struck closer to midships.

Both detonated.

The ship’s hull buckled. Secondary explosions ripped through her. Men were thrown into the air; fire and smoke boiled up as Wilkins pulled up and banked hard.

He had done his job. One warship down. But his B-25 was badly hurt.

A Wounded Bird and a Terrible Choice

Coming off the attack run, Wilkins realized something was very wrong with his aircraft.

The B-25’s vertical stabilizer—its tail fin—had been shot away. The tail section was torn open. Hydraulic systems were failing. The aircraft wallowed and wanted to roll. Keeping it in the air was a fight.

Behind him, the remaining B-25s were finishing their attacks. Two more destroyers were hit. A transport at the dock exploded into flames. The harbor was a boiling chaos of fire, water, and steel.

But now the sky was filling with fighters.

Zeroes from carrier air groups and land bases swarmed over Simpson Harbor. One B-25 exploded when cannon rounds found its fuel tanks. Another was chopped from the air by precise, deadly anti-aircraft fire. Wreckage smashed into the sea with no parachutes and no survivors.

Those who survived the initial run began clawing for altitude, trying to escape the worst of the lower-level fire and head for the relative safety of open ocean.

Wilkins, tail shot nearly off, struggled to keep Fifi flying at all. His instruments showed his engines were still running—oil pressure good enough, temperatures high but not yet fatal. Hydraulics were gone. Landing gear would have to be cranked down by hand if they ever reached a runway. Fuel was leaking, but not enough—yet—to doom them.

Then he saw it: a Japanese heavy cruiser ahead, its guns tracking his fleeing squadron.

At that moment, Major Wilkins had two choices, and he knew exactly what they were.

One: turn away, limp out of the harbor, and try to nurse his battered bomber home. He had already sunk a destroyer. His aircraft was crippled but flyable. Standard procedure said: you’ve done your part, get out while you still can.

Two: turn back into the hell he had just survived, fly a second low-level attack against a heavily armed cruiser with no bombs left, just guns, and draw its fire away from his men.

The kid in the right seat—on just his third mission—looked at him and waited.

Wilkins shoved the throttles forward and banked toward the cruiser.

The Run That Saved Five Crews

It was a suicide run in everything but name.

The cruiser loomed ahead at 800 yards. Wilkins dropped to about 50 feet above the water. With his tail shot apart and control surfaces damaged, flying that low was like balancing on a knife edge.

At 600 yards, every gun on the ship opened fire.

Forty-millimeter, 25 mm, 13 mm machine guns—an absolute wall of fire. Tracers stitched across the sky, a solid curtain that Wilkins deliberately flew into.

His windscreen shattered. Glass shards filled the cockpit. A round tore into his left arm. Pain flared white hot, but he kept his finger down on the trigger and his damaged aircraft pointed straight at the cruiser.

The B-25 was coming apart. Holes bloomed in the wings—ragged, smoking. One engine began to cough. But the heavy machine guns spat fire the entire way in.

The cruiser’s deck, superstructure, and bridge vanished behind a storm of .50-caliber rounds. Gun crews were cut down in their positions. Others dove flat or scrambled for any bit of cover. The bridge took repeated hits; windows exploded; metal peeled away.

Hundreds of enemy eyes that had been tracking American bombers fleeing the harbor were now locked on one single, doomed aircraft.

At around 100 yards, Wilkins released the trigger and hauled back on the control column, using engine power as much as what was left of his tail to drag the nose up. His B-25 cleared the cruiser’s mast by maybe 20 feet.

He had done it. He’d drawn the fire. The cruiser had stopped tracking his squadron. Its guns, and many of the harbor batteries, had been focused entirely on him.

Behind Wilkins, five B-25s clawed for the harbor exit. They were damaged, bleeding fuel and hydraulic fluid, but alive. Those precious seconds where the cruiser wasn’t shooting at them made all the difference.

The cost was immediate.

One of Wilkins’s engines seized. He feathered the propeller and tried to coax the wounded bomber toward the open sea.

Then the fighters came.

Alone in the Sky

Three Zeros dove from above. Two split off; one came straight in along the centerline.

The top-turret gunner opened up, sending tracers arcing toward the attacking fighters. The Zero kept coming. Cannon shells crawled up the B-25’s fuselage, tearing through the radio compartment. Screams sounded over the intercom, then cut off.

More Zeros appeared. Four. Six. Eight.

Wilkins could not out-turn them. He couldn’t outrun them. His remaining engine was already straining. The wounded aircraft was generating so much drag that every gain in speed was temporary.

Fighters hit his left wing, rupturing a fuel tank. Gasoline streamed back along the surface. One spark, one tracer in the wrong place, and Fifi would become a fireball.

He pushed the nose down to gain airspeed, trading altitude for a fragile chance at control. But dropping lower brought him back into range of anti-aircraft guns along the coastline.

There were no good choices left.

Despite everything—the destroyed tail, the shredded wing, the fuel leak, the fighters—Wilkins managed to get the B-25 over open water. The coastline dropped behind them. Sea spread ahead.

And then, finally, the last good engine died.

Sudden silence filled the cockpit, broken only by wind whistling over torn metal and the distant snarl of enemy engines.

He had just enough altitude for one attempt at ditching.

The Last Minutes of Major Wilkins

The B-25 descended toward the Pacific, more glider than airplane now. At about 90 knots, Wilkins lined up parallel to the swells. He gave his surviving crew brief instructions over the intercom about ditching procedures.

They didn’t have life rafts. They were far behind enemy lines. Rescue, if it came at all, would be sheer luck.

The impact was violent.

The nose dug in. Water slammed through the broken windscreen, filling the cockpit. The fuselage buckled and twisted. In seconds, the bomber began to sink nose-first.

Wilkins and his co-pilot fought their harnesses, groped for the overhead escape hatch. It was jammed. Impact had warped the frame. Water rose from their ankles to their chests as they heaved against it.

On the second try, leaning on his good arm, Wilkins helped force the hatch open. Water surged in even faster. He shoved his co-pilot up first, then tried to follow.

His left arm wouldn’t respond. He slipped back into the cockpit, briefly submerged in the dark flood. He fought his way up again, lungs burning, and somehow got clear.

On the surface, the shattered remains of Fifi hung for a few seconds tail-up before sliding under for good. The radio operator and waist gunner never came out.

Wilkins and his co-pilot bobbed in the waves, 50 miles from friendly territory.

Zeros circled overhead. One made a low pass. Wilkins must have expected gunfire.

Instead, the Japanese pilot waggled his wings in a brief salute and flew away.

Soon, the sky was empty. Just two men, the wide Pacific, and the slow drain of blood from a serious wound.

The co-pilot held onto Wilkins as long as he could. For forty minutes, he fought the sea and the weight of another human being. Eventually, exhaustion forced an impossible choice: let go, or both drown.

He let go.

Major Raymond Harold Wilkins slipped beneath the surface and did not come back up. His body was never recovered. He was 26 years old.

Strategic Victory, Human Cost

Back at Dobodura, New Guinea, surviving B-25s from the raid limped home.

Five aircraft from Wilkins’s squadron made it back to Allied airspace. Some trailed smoke. One flew on a single engine. Another arrived with half its tail missing. Ground crews counted more than 300 holes in one airframe. Hydraulics were gone. One bomber ran off the runway on landing; the crew walked away shaken but alive.

In all, that day—later known as “Bloody Tuesday”—was the single bloodiest day the Fifth Air Force had experienced in the Pacific campaign. Eight B-25s and nine P-38s were shot down. Forty-five airmen were dead or missing.

The casualty reports were stark. So were the results.

Debriefings and reconnaissance photos told the story:

One destroyer sunk by Wilkins’s initial attack

Another destroyer broken in half and sinking

A transport ship ablaze at the dock, ammunition exploding

A heavy cruiser heavily damaged, guns silenced during the bombers’ withdrawal

Multiple ships destroyed or rendered inoperative

Japanese records later confirmed that Rabaul’s harbor defenses had been overwhelmed. Seven ships were sunk or severely damaged. Eighteen Zero fighters were destroyed; twelve more were damaged beyond repair. Many of the pilots lost were elite aviators from the carriers Zuikaku, Shokaku, and Zuihō—men Japan could no longer easily replace.

Most important of all: in the days that followed, Japanese ships at Rabaul stayed in harbor. No cruisers or destroyers sortied to strike the Marines on Bougainville. The beachhead held. Reinforcements arrived. The invasion succeeded.

In cold numbers, the trade looked like this: 45 American airmen for a crippled fortress, smashed ships, killed pilots, and a secured landing that would help drive Japanese power back toward the Philippines.

In human terms, it was much harder: 45 sons, brothers, husbands, and friends who would never see home again.

A Medal and a Memory

Within days, reports began to converge around one name: Major Raymond H. Wilkins.

Survivors testified that he had sunk a destroyer on his first pass, then turned back in a crippled bomber to attack a heavy cruiser with only his guns. They described how his run drew away fire and allowed five other B-25s to escape the harbor. They told of his ditching at sea, the struggle to get out, and the last moments before he slipped beneath the water.

His squadron commander recommended him for the Medal of Honor on November 5. Statements from fellow airmen followed. The paperwork climbed the chain of command—group, wing, Fifth Air Force headquarters. General George Kenney, who commanded air operations in the Southwest Pacific, reviewed the case personally.

He had seen many Medal of Honor recommendations. Most did not make it through. The standards were intentionally high.

Wilkins’s case did.

The record was clear: in the face of certain death, he had turned into danger, not away from it, to save others. He had demonstrated “conspicuous gallantry and intrepidity at the risk of his life above and beyond the call of duty.”

By January 1944, President Franklin D. Roosevelt had approved the award.

In California, Wilkins’s family received the telegrams no family wants: first the notification of his death, then the announcement of his award. At a later ceremony, they accepted the Medal of Honor on his behalf.

The girl in Australia he had planned to marry found out through unofficial channels. A letter he had written four days before the raid arrived after the news of his death. In it, he talked about feeling his luck running out, about the odds, about how almost everyone from his original group was already gone. He also wrote about duty—and about the future they would share when the war ended.

He never reached mission number 88. The future he described in ink ended in cold water off Rabaul.

Pride in the People Who Choose to Serve

Today, if you walk through the Air Force Museum at Wright-Patterson in Ohio, you can find a small display case. Inside are a photograph of a young officer, a Medal of Honor, and a brief paragraph describing a mission over Rabaul.

Most visitors walk past. There are thousands of stories in that building. Not all of them get the time they deserve.

But for those who stop and read, who picture a damaged bomber at 50 feet above Simpson Harbor, its nose blazing with machine-gun fire, its pilot steering straight into a wall of tracers so his men have a chance to live—something becomes very clear.

The pride Americans feel in their military isn’t just about victories, or ships, or medals. It’s about the people who, when the moment comes, choose to put their own survival second.

Major Raymond Wilkins didn’t fly toward that cruiser because anyone ordered him to. He did it because five other crews were in danger and he believed his life was a fair price to pay for theirs.

The Marines on Bougainville never knew his name. They didn’t need to. Their job was to fight on the ground. His was to make sure Japanese ships didn’t show up offshore to blast them into the sea.

That’s what service looks like: doing your duty so well that complete strangers get to live, build families, and grow old because you didn’t.

Keeping the Story Alive

The raid on Rabaul became legendary in Fifth Air Force. The low-level tactics proved there were no truly “safe” harbors for enemy ships. Skip bombing became standard doctrine. B-25s across the theater were modified with forward-firing guns like those on Fifi. Crews trained using techniques that had been refined—and paid for—by men like Wilkins.

Rabaul itself was eventually isolated, bypassed, and left to wither, its garrison cut off until the end of the war. The fortress that had consumed so much planning and blood never fell to a dramatic final assault. It simply ceased to matter.

The war moved on. Units rotated home. New crews arrived to replace those who had given everything. The original members of the Third Bombardment Group were gone by mid-1944—dead, reassigned, or finally sent home after impossible tours.

Reunions came and went in the decades after the war. Veterans gathered to remember names, faces, missions, planes. They told stories about good leaders and bad ones, about commanders who turned away from danger and sergeants who refused to let their men down. They raised glasses to the ones who weren’t there.

They always mentioned Wilkins.

As the years passed, their numbers dwindled. Obituaries shrank their war service down to a paragraph. The living memory of Bloody Tuesday faded as those who were there left this world.

What remains is the story—and what that story tells us about who we are.

Why This Matters Now

There’s a temptation to see World War II as distant and inevitable: a war of “greatest generations,” of clear enemies and clear victories. But none of it was guaranteed.

Every inch gained, every island taken, every beachhead held depended on regular Americans making impossible decisions in impossible conditions.

Major Raymond Harold Wilkins was a kid from California who could have come home after a handful of missions, put on a suit, and disappeared into a peacetime crowd. Instead, he climbed into a bomber again and again, 87 times, knowing that the odds were getting worse every day.

On his last mission, he watched a second of opportunity open in front of him and chose to spend his life in that moment so that others had a chance to live.

That’s what we honor when we talk about pride in our military—not just power, not just technology, but character.

Men and women like Wilkins don’t just win battles. They define what it means to be an American in uniform:

To accept risk others don’t.

To carry responsibility others never feel.

To lay down a future so others can have one.

His B-25 lies somewhere on the floor of the Pacific now, its metal slowly dissolving into salt and time. But the lives he saved flew home, started families, built communities, and raised children and grandchildren who may never know exactly why they exist.

They exist because, on November 2, 1943, a 26-year-old major over Simpson Harbor believed their lives mattered more than his own.

That is worth remembering. That is worth being proud of.

News

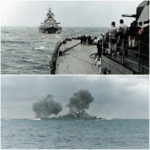

The Bismarck – How the World’s Most Feared Battleship Lasted Only Eight Days at Sea

At 2:48 a.m. on May 24, 1941, in the freezing darkness of the Denmark Strait, a British officer lifted his…

They Said the Shot Was ‘Impossible’ — Until He Hit a German Tank 2.6 Miles Away

At 10:42 a.m. on December 1, 1944, a young American lieutenant leaned into the eyepiece of a gun sight and…

Germans Couldn’t Believe This Destroyer Rammed Them — Until 36 Fought Hand-To-Hand With Coffee Mugs

Coffee Mugs and Courage: How USS Buckley Turned a Night Battle into an American Legend On an ordinary day at…

This 19-Year-Old Was Flying His First Mission — And Accidentally Started a New Combat Tactic

THE DIVE THAT CHANGED EVERYTHING How a 19-Year-Old West Virginia Mechanic Broke Every Rule, Outflew the Luftwaffe’s Elite, and Accidentally…

They Banned His Forest Floor Sniper Hide — Until It Took Down 18 Germans

THE SOLDIER IN THE MUD How a South Philadelphia Rifleman Broke the Rules, Revolutionized Sniper Tactics, Was Court-Martialed—And Quietly Saved…

They Mocked His ‘Medieval’ Crossbow — Until He Killed 9 Officers in Total Silence

🤫 The Silent Assassin of the Hürtgen: How a Philly Dockworker Reintroduced the Crossbow to WWII Private First Class…

End of content

No more pages to load