The 6-Inch Secret: How a Technical Sergeant Broke Every Rule with a Piece of Piano Wire to Save the P-38 Lightning and Turn the Tide in the Pacific Sky

I. The ‘Tin Can’ of the Air: The P-38’s Fatal Flaw

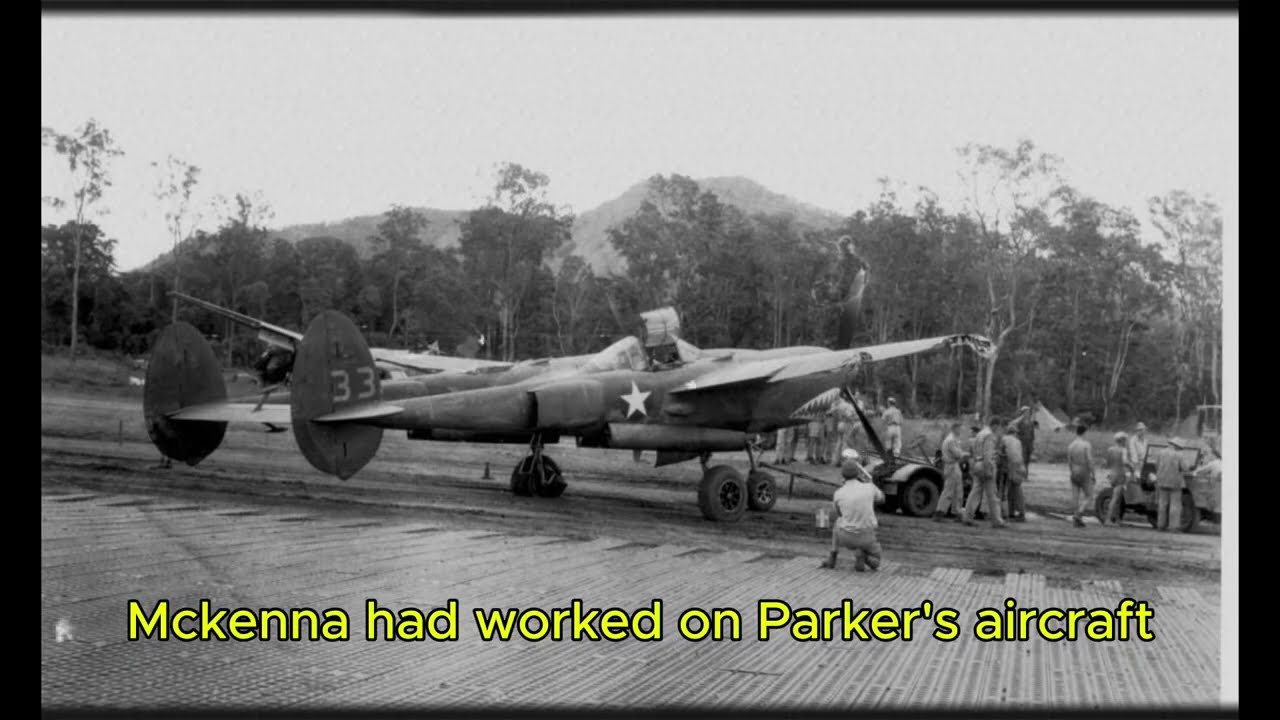

The summer of 1943 in the Southwest Pacific was a period of grinding, brutal air combat. The United States Army Air Force (USAAF) relied heavily on the Lockheed P-38 Lightning—a twin-engine, twin-boom fighter that was fast, formidable, and capable of operating at high altitudes. American propaganda hailed it as a technological marvel.

However, on the dusty airfields of New Guinea, the P-38 was earning a darker reputation. Its fatal flaw was universally known and ruthlessly exploited by the enemy: It couldn’t turn with a Zero.

The Japanese Mitsubishi A6M Zero was lighter, more agile, and could execute a full horizontal turn in half the time the P-38 required. In the close-quarters dance of a dogfight, this difference meant instantaneous death. The American doctrine for P-38 pilots was absolute: Never turn with a Zero. Use speed. Use altitude. Dive in, shoot, climb out—Hit and Run.

Yet, the doctrine was failing. Pilots, often young and inexperienced, were being baited by the cunning Zero pilots into turning fights, their superior maneuverability allowing the Japanese to cut inside the P-38’s turning radius, get on their tail, and shoot them down. The Fifth Air Force had lost 37 P-38s in six weeks in turning engagements they couldn’t escape.

A. The Mechanics of Death: A Quarter-Inch of Slack

Technical Sergeant James McKenna, a P-38 crew chief with eight months of grueling maintenance experience in the tropical heat, knew the aircraft inside and out. He watched too many “good men, kids, really” climb into their Lightnings and return in boxes, or not return at all. While the official reports blamed “pilot error” and a failure to follow doctrine, McKenna knew the brutal truth was mechanical.

The P-38’s aileron control cables, which ran a complex route through the twin booms to the tail and forward to the wing surfaces, had a small, accepted engineering flaw: slack.

“The cable system had slack. Not much, maybe 3/8s of an inch at full deflection. But that tiny bit of slack created a delay between stick movement and aileron response. At low speeds during hard turning maneuvers, that fraction of a second delay was the difference between rolling inside a Zero’s turn and getting shot down.”

McKenna had reported it. The engineering officer dismissed it: cable tension was “within specifications.” Factory tolerances allowed it. Modifying it would void the warranty and required approval from Lockheed—7,000 miles away in California. Bureaucracy, warranty agreements, and paperwork were, literally, killing American pilots.

II. The Line in the Sand: Hayes’s Mission

On the evening of August 16th, Lieutenant Robert Hayes, a 23-year-old farm kid from Iowa with six combat missions and zero kills, approached McKenna. Hayes, having just watched his wingman die because his aircraft “wasn’t turning fast enough,” was desperate. He knew he was going to die if something didn’t change.

Hayes pleaded with McKenna: “Anything you can do to make the airplane roll faster… I just wanted a chance.”

McKenna, seeing the fear and desperation in the young pilot’s eyes, agreed. He knew the risk: unauthorized modification to a flight control system meant a court-martial, possibly a dishonorable discharge, or even prison time if the modification failed. But the alternative was watching another pilot die.

Under the cover of night, in the quiet, humid maintenance hangar, McKenna went to work alone.

A. The Unauthorized Solution: Piano Wire

From a salvaged, damaged P-38, McKenna retrieved a piece of high-tensile piano wire—a six-inch section from the rudder trim system he had kept in his toolbox. Using a pair of pliers, he bent the stiff wire into a Z-shape.

The Z-shape would serve as an inline tensioner.

Working in the tight, cramped space inside the P-38’s left boom structure, fumbling with clevis pins and fighting against the risk of discovery, McKenna disconnected the aileron control cable at the pulley junction. He inserted the piano wire tensioner, forcing the cable back into position.

“When it finally seated, he tested the tension by hand, pulled on the cable. No slack. The control surface moved immediately. Perfect.“

The modification took eight minutes. It added a negligible 0.4 pounds of tension. It eliminated the slack completely. Nobody noticed. McKenna said nothing. He simply replaced the inspection panel and wiped the blood from his cut thumb and the piano wire.

At 07:42 a.m. on August 17th, 1943, Lieutenant Hayes took off toward 18 waiting Japanese Zero fighters.

III. The Seven-Minute Miracle: The Lightning Finds Its Speed

The engagement began at 08:14 over the Huon Gulf. Hayes was flying a diving attack. The Zero he targeted snap-rolled right and dove to evade.

Hayes rolled to follow, and instantly, he felt it.

“The airplane responded instantly. No delay, no lag. The stick moved and the aircraft rolled immediately. Hayes had never felt his P-38 move like that… It was like the airplane had been waiting for his command and executed it the moment he gave it.”

He rolled 90 degrees in what felt like half the normal time. He got his nose down, the Zero was right in his sight. He fired a three-second burst. The Zero’s engine exploded and it fell toward the jungle.

Hayes’s first kill.

But the Zeros retaliated immediately, diving for revenge. Hayes’s only option was to reverse and fight—the maneuver that had killed 37 P-38 pilots.

He rolled hard left and pulled. The P-38 “snapped around like nothing he’d ever experienced.” The lead Zero, expecting the traditional P-38 delay, was now suddenly exposed. Hayes got guns on him and the Zero tumbled.

Two kills in 30 seconds.

The remaining Zeros tried to use their signature scissor tactics, alternating turns to force an overshoot. But Hayes stayed with them. His P-38 snapped into every turn instantly. It was like flying a different aircraft. When one Zero bled too much speed, Hayes slipped inside his turn and fired at close range. The Zero came apart.

Three kills. The fourth Zero ran.

The entire engagement lasted seven minutes. Hayes landed, hands shaking, soaked in sweat, and walked straight to McKenna with two words: “It worked.”

IV. The Whisper Network: An Underground Modification

The incredible kill ratio was impossible to ignore. Captain Frank Mitchell, a respected flight leader, had watched the entire engagement from altitude and noted that Hayes’s P-38 was rolling faster than any Lightning he had ever seen.

Mitchell tracked down McKenna. The sergeant, covered in grease, admitted everything: “The piano wire tensioner, the cable modification, the unauthorized change to the flight control system.”

Mitchell’s response was immediate: “I don’t care. I’ve lost four pilots in my flight in the past month. Regulations can wait.”

The following night, McKenna modified Mitchell’s P-38. Mitchell flew it the next morning and returned “raving about the improvement.”

The piano wire modification spread through the ranks like a life-saving virus:

Pilot-to-Pilot: Pilots demanded the change after seeing the results.

Mechanic-to-Mechanic: Crew chiefs, convinced by the rising survival rates, learned the simple eight-minute process from McKenna.

The Deception: Crew chiefs removed the tensioners before official inspections and reinstalled them afterward, keeping the engineering officers and the maintenance hierarchy in the dark.

By early September, an estimated 40 P-38s in New Guinea had the “McKenna Modification.”

The statistics shifted dramatically: | Period | P-38 Losses per Zero Destroyed | | :— | :— | | July 1943 | 2 to 1 | | August 1943 | 1.3 to 1 | | September 1943 | 1 to 1 (or better) |

For the first time in the Pacific War, the P-38 Lightning was killing Zeros at a better than one-to-one rate.

V. The Confusion of the Enemy: Sakai’s Frustration

The Japanese High Command soon noticed the inexplicable shift. Flight reports from the 11th Air Fleet noted that P-38s were maneuvering more aggressively, rolling faster into turns, and reversing direction more quickly. Tactics that had worked reliably for months were suddenly failing.

Lieutenant Commander Saburo Sakai, one of Japan’s top aces with 64 confirmed kills, experienced the shocking change firsthand on September 3rd, 1943, over Wewak.

Sakai used his standard tactic—bait the P-38 into a roll, then snap-turn back the opposite way to get inside the American’s turning radius.

“Except the P-38 reversed with him. Sakai had executed this maneuver dozens of times… But this P-38 rolled faster than it should have. Sakai barely avoided a head-on collision. The American got guns on him. Sakai had to dive away.”

Sakai returned to base confused and frustrated. The Americans weren’t flying differently; their aircraft were responding fractionally faster, enough to disrupt the perfect timing the Japanese pilots had learned to exploit.

Japanese intelligence was baffled. They examined wreckage from downed P-38s but found no obvious modifications. It wasn’t a new engine or a new weapon system. It was hidden inside the boom: a small, Z-shaped piece of piano wire that looked like original equipment. Even if they had found it, they might not have understood its life-saving purpose.

The psychological impact was devastating. The Zero pilots’ confidence—that they owned the sky in a turning fight—was broken. They became cautious, hesitant. The Japanese were forced to adapt by fighting like P-38s, using hit-and-run tactics, which meant giving up their main advantage of maneuverability.

By the end of September, the Zero had gone from hunter to hunted.

VI. The Bureaucracy Catches Up: Validation Without Credit

The unofficial modification eventually reached the official chain of command in October 1943 when a maintenance inspector, noticing inconsistent cable tension readings, traced the discrepancies back to the piano wire tensioners.

The report caused a month of agonizing debate among Army Air Force officers: Should they punish the mechanics who violated regulations, or quietly approve the modification that was clearly saving lives?

In November, Lockheed sent an engineering team to New Guinea. They tested the modification, calculated the stress loads, and ran flight tests.

Their conclusion was a resounding victory for the enlisted man: The modification was safe and effective. It should have been part of the original design.

Lockheed integrated a similar, refined tensioning system into the P-38J model that entered production in December 1943, permanently fixing the fatal flaw.

However, Technical Sergeant James McKenna never received official credit. No commendation, no medal, no mention in any official report. Lockheed attributed the improvement to “engineering analysis.”

VII. The Silent Legacy of the Mechanic

McKenna stayed in the Army Air Force until 1946 before returning to Long Beach, California, where he opened his own garage and spent the next 42 years working on cars. He never talked much about the war, simply saying he was a mechanic who fixed airplanes.

The men he saved never forgot.

Lieutenant Robert Hayes (11 kills) survived the war, became a crop duster, and called McKenna every year on August 17th to thank him for saving his life.

Captain Frank Mitchell (16 kills, retired as a Colonel) stayed in the Air Force and told McKenna’s story to every young maintenance officer he supervised, ensuring they understood that sometimes the best solutions come from the enlisted ranks who see problems the engineers miss.

In 1991, a military historian tracked down the 73-year-old McKenna and confirmed the story of the piano wire tensioner. The historian estimated that the simple, unauthorized modification may have saved between 80 and 100 American pilots’ lives.

McKenna’s response was characteristic of the quiet hero: “It wasn’t anything special, just something that needed doing.”

Technical Sergeant James McKenna died in 2006. His obituary mentioned his service in World War II as an aircraft mechanic. It did not mention the piano wire tensioner. It did not mention that he had, by breaking every rule, changed how American fighters flew and helped turn the tide of the Pacific air war.

His story remains a powerful testament to the true nature of innovation in combat: It happens not through official channels or engineering committees, but through sergeants and mechanics who see a problem, find a solution, and don’t wait for permission to save lives.

News

This B-17 Gunner Fell 4 Miles With No Parachute — And Kept Shooting at German Fighters

The Day the B-17 Broke At 11:47 a.m. on November 29th, 1943, the sky above Bremen, Germany, was a…

They Mocked This Barber’s Sniper Training — Until He Killed 30 Germans in Just Days

On the morning of June 6, 1944, at 9:12 a.m., Marine Derek Cakebread stepped off a British landing craft into…

They Mocked His ‘Mail-Order’ Rifle — Until He Killed 11 Japanese Snipers in 4 Days

🎯 The Unconventional Weapon: How John George’s Civilian Rifle Broke the Guadalcanal Sniper Siege Second Lieutenant John George’s actions…

” We All Will Marry You” Said 128 Female German POWs To One Farm Boy | Fictional War Story

The Marriage Petition: The Nebraska Farm Boy Who Saved an Army of Women With a Choice, Not a Shot …

“German Mothers Wept When American Soldiers Carried Their Babies to Safety in WW2”

The Unplanned Truce: How Compassion Crumbled the Propaganda Wall Near Aken, 1944 In the Freezing Ruins of Germany, American…

Japanese Female Nurses Captured SHOCKED _ When U.S Doctors Ask for their help in Surgery

The Unbroken Oath: How Japanese Nurses Shattered Propaganda By Saving American Lives in a Field Hospital in 1945 Behind…

End of content

No more pages to load