THE HAY BALE GAMBIT

How One Iowa Farm Boy Captured 34 German Soldiers Alone—Without Firing a Shot—And Accidentally Redefined Small-Unit Psychology in WWII

At 7:47 a.m. on September 18, 1944, in a misty Dutch field outside Eindhoven, a rectangular hay bale sat quietly beside a stone wall. The bale looked like every other one scattered across the farmland—weathered straw bound with twine, dew-soaked, steeped in the scent of a damp European September.

Thirty-four German soldiers marched straight toward it.

They were tired—trudging after a night march, unaware they were isolated behind enemy lines. Their movements were sloppy. Their rifles hung low. Their sergeant smoked a cigarette, pausing only to complain about rations.

None of them knew the hay bale wasn’t a hay bale.

Inside the compressed mass of straw, crouched impossibly tightly, sat Private Thomas “Tommy” Bartlett of the 101st Airborne Division. His knees were numb. His shoulders ached from hours of stillness. His M1 Garand lay across his lap with eight rounds—rounds he hoped he would not need to fire.

He had no radio.

No backup.

No escape route.

And in the next forty minutes, he would capture all thirty-four Germans alone, without firing a single shot.

He would do it by using nothing taught in any infantry manual—nothing learned in paratrooper school, nothing coached by officers. He would succeed using the quiet skills of a farm kid from Iowa: livestock psychology, pattern recognition, and an understanding of how tired creatures—human or animal—react under stress.

His commanders would briefly consider giving him a medal, then quietly bury the story in paperwork.

His fellow soldiers would treat it as a hilarious rumor—until several of them tried it themselves and discovered it worked.

And military historians, decades later, would call it one of the most unusual, effective, and revealing battlefield deceptions of World War II.

This is the story of the hay bale gambit—of ingenuity born not from tactics, but from fields of wheat.

FARM KID IN A MILITARY MACHINE

Thomas Bartlett grew up outside Cedar Rapids, Iowa, where his father ran 340 acres of wheat and corn. The Bartlett farm was not prosperous. It survived only through relentless labor. From childhood, Tommy’s days were shaped by rhythms older than the nation he served: harvesting cycles, cattle movements, and the perpetual maintenance of machinery.

He learned to drive a tractor at nine.

Fix a combine at twelve.

Predict weather by watching cattle behavior at thirteen.

He grew up handling 500-pound rectangular hay bales—objects dense enough to break fingers if mishandled, light enough to be maneuvered with leverage rather than brute strength. He learned that cows, under stress, followed the behavior of the animal ahead of them rather than the commands of the farmer behind them.

“Thomas sees systems where others see chaos,” his high school agriculture teacher wrote in a recommendation letter.

He was drafted in January 1943.

He turned nineteen during basic training at Fort Benning. While drill sergeants screamed about aggression and discipline, Bartlett simply noticed—noticed the cracks in doctrine, the unreliability of human behavior under pressure, the ways real life deviated from the diagrams in infantry manuals.

When a paperwork error assigned him to the 101st Airborne Division’s 506th Parachute Infantry Regiment, he didn’t correct it.

He attended jump school.

He landed in Normandy on D-Day tangled in a tree, cut himself down, and walked fourteen miles alone to the rally point.

His lieutenant called it “initiative under fire.”

Bartlett simply called it “finding the barn when the cows scatter.”

FRANCE: WHERE PATTERNS TURNED INTO DEATH

Normandy changed him.

On June 12, 1944, Private First Class Danny McKinnon—who had shown Bartlett photos of his twin daughters the night before—took a sniper round through the throat while crossing a hedge near Carentan. He drowned in his own blood in forty-seven seconds.

Three days later, Corporal James Chen stepped on a Teller mine.

The explosion disintegrated his legs.

He screamed for his mother for six minutes before morphine took effect.

On July 8, Staff Sergeant Michael Donovan—Bartlett’s respected squad leader—was cut down by an MG42 machine gun. Eleven rounds tore across his chest. He died whispering for his men to keep moving.

By September, Bartlett had watched eighteen men from his company die in France.

Not because they lacked courage.

Not because they lacked skill.

They died because doctrine assumed all battlefields were identical.

Cross the hedgerow.

Advance in formation.

Flank the machine gun.

Clear the orchard.

Follow the manual.

Except sometimes the orchard was mined.

Sometimes the hedgerow concealed a sniper.

Sometimes the field offered no flank.

Bartlett began deviating.

He crossed hedgerows at angles not in the manual.

He waited thirty seconds longer before moving.

He studied German firing patterns instead of rushing forward.

His lieutenant noticed—but didn’t stop him. Bartlett’s squad took fewer casualties than others.

He didn’t call his choices tactical innovation. He called it the way the world actually works.

OPERATION MARKET GARDEN: A CLEAN PLAN MEETS MUDDY REALITY

On September 17, 1944, Bartlett jumped into Holland as part of Operation Market Garden—a bold Allied plan to seize bridges deep behind German lines.

The plan unraveled quickly.

German resistance was heavier than expected.

Intelligence about enemy presence was disastrously wrong.

Airborne units found themselves scattered, cut off, and understrength.

Roads meant to be “secure” were alive with German patrols trying to rejoin their units.

Bartlett’s platoon from Easy Company secured a crossroads northeast of Eindhoven—a position regimental headquarters believed held no German threats.

That belief proved dangerously optimistic.

Throughout the evening, Bartlett noticed the pattern: scattered groups of German soldiers—stragglers separated from their units—moving across farmland with the swagger of men who believed themselves safely behind their own lines.

Some fought.

Some surrendered.

Most were exhausted, hungry, and disoriented.

Lieutenant Marcus Hayes gathered the platoon at sundown.

“Intel wants prisoners,” he said. “These stragglers don’t know the sector is swarming with us. If you can capture instead of kill, do it.”

Bartlett absorbed the instruction quietly.

Prisoners were valuable.

Lives—American lives—were even more valuable.

That night, staring at the scuffed hay bales scattered around the abandoned farm, an idea began to take shape.

THE PLAN NO MANUAL WOULD EVER SANCTION

At 11:30 p.m., Bartlett approached Lt. Hayes.

“Sir, I need permission to try something.”

Hayes—twenty-three years old, former high school history teacher—looked up.

“What kind of something?”

Bartlett laid out his idea.

It hinged on four facts:

The Germans marching through the area believed they were behind friendly lines.

Exhausted soldiers made predictable decisions.

Fog muffled sound and distorted its direction.

Hay bales were perfect concealment, provided you understood how to hollow one out without changing its appearance.

Hay bales.

White flag.

Fog.

German exhaustion.

Agricultural psychology.

Live-action misdirection.

Hayes stared at him.

“If you get killed,” he said, “I’ll write your mother a very unflattering letter. If this works, you’ll get a commendation you’ll probably never receive. You have until dawn.”

“Thank you, sir.”

“And Bartlett?”

“Yes, sir?”

“Don’t die stupidly.”

THE HAY BALE

At midnight, Bartlett went to work inside the abandoned barn.

He selected one intact bale—slightly weathered, tightly packed but not brittle. Using his KA-BAR knife, he carved a human-sized chamber inside the bale. Every handful of hay removed was carefully stuffed into already-damaged bales to disguise disturbance.

By 1:15 a.m., he had created a cavity large enough to crouch inside, rifle and all.

The smell of hay and Iowa autumn filled his nostrils. For a moment, a wave of homesickness almost broke him. Then he remembered McKinnon, Chen, Donovan—and kept working.

He placed the hollowed bale thirty meters from the road, tucked behind a low stone wall. Three intact bales masked the opening.

Then he tore a white bedsheet into a crude surrender flag.

By 4:30 a.m., he crawled into the hay bale, knees already aching, rifle across his lap, white flag tucked at his waist.

He waited.

THE GERMAN COLUMN

At 7:30 a.m., he heard them.

Boots on dirt.

Shuffling.

Muttering.

The lead sergeant cursing about rations.

The column emerged from the fog—thirty-four men in loose formation.

Tired.

Unsuspicious.

Behind their own lines—supposedly.

They passed twenty meters from Bartlett.

No one so much as glanced at the hay bales.

Bartlett waited until they disappeared into the fog.

Then he counted to thirty.

Crawled out.

Nearly collapsed from numbness.

Grabbed his rifle and white flag.

And followed them from fifty meters back, moving cover-to-cover.

At 8:10 a.m., the Germans halted at a crossroads and relaxed—packs down, cigarettes lit, discipline slackened.

Time.

THE DECEPTION

Bartlett circled ahead of the Germans, moving through fog until he was thirty meters in front of them behind an overturned farm cart.

Then he stood.

The Germans snapped to alert. Rifles aimed.

Bartlett raised the white flag.

And shouted—in flawed but effective German he had learned from a captured soldier:

“Amerikaner! Überall! Ihr seid umzingelt!”

Americans! Everywhere! You are surrounded!

He pointed behind them dramatically.

They spun, rifles trembling, scanning the fog.

Bartlett fired one round into the air—then sprinted laterally through fog to a new position.

From behind a stone wall he shouted again:

“Hunderte Amerikaner!”

Hundreds of Americans!

He fired another round—then moved again.

From behind a cluster of hay bales he shouted:

“Kein Entkommen! Amerikaner kommen!”

No escape! Americans coming!

The Germans swiveled helplessly, hearing “multiple” shooters from three different directions.

Fog transformed one voice into many.

Exhaustion turned nerves into panic.

And then submission became contagious.

Two soldiers dropped their rifles and raised their hands.

Five more followed.

The sergeant shouted at them to hold formation—but fear overtook discipline.

Within minutes, half the men had surrendered.

Finally, trembling, the sergeant lowered his weapon.

“We surrender!” he shouted.

At 8:47 a.m., Bartlett marched thirty-four German soldiers into the American perimeter alone.

REACTION: DISBELIEF AND ANGER, FOLLOWED BY QUIET ACCEPTANCE

Lieutenant Hayes stared for several seconds.

“Private Bartlett,” he said slowly, “what the hell…?”

“Prisoners, sir.”

Eddie Sullivan from Brooklyn burst out laughing.

“Holy hell, Farmboy actually did it!”

Interrogation officers were baffled.

“How many men were with you?” one German sergeant was asked.

“Thirty, maybe forty,” he replied. “Surrounded from three sides.”

“How many were actually with you?” the interrogator asked Bartlett.

“Just me, sir.”

“Explain.”

Bartlett laid out the entire method: hay bale hide, positional deception, fog acoustics, white flag manipulation, voice projection across terrain, psychological timing.

The interrogator—for all his rank and training—didn’t know what to make of it.

“This violates at least seven tactical guidelines.”

“Yes, sir.”

“You could have been killed.”

“Yes, sir.”

“Why did you do it?”

Bartlett thought of McKinnon choking on blood, Chen screaming for his mother, Donovan dying in his arms.

“Seemed safer than a firefight, sir.”

THE SPREAD OF A WHISPERED TACTIC

The next day, Sergeant Robert Chen of Baker Company tried a modified version—without hay bales. Using fog and voice deception, he captured nineteen Germans with no shots fired.

Word spread—not up the chain of command, but sideways, soldier to soldier, the underground pipeline where the real tactical innovations of war often travel.

By late October, six similar captures occurred in the 101st Airborne alone.

German reports noted:

“American infantry increasingly employs deception instead of direct assault.

Movement behind assumed friendly lines no longer safe.”

Effect: German patrol movements slowed, discipline tightened, vulnerability increased.

American casualty rates from patrol engagements dropped nearly 40 percent between September and November.

One battalion report estimated roughly sixty American lives saved across the regiment.

Unconventional, unsanctioned, and unofficial—Bartlett’s idea worked.

No manual had predicted it.

No officer had suggested it.

No strategist had modeled it.

It spread because it helped men live.

WHAT THE ARMY DID—AND DIDN’T—DO WITH IT

Lieutenant Hayes submitted Bartlett’s name for a Bronze Star.

Battalion headquarters rejected it.

“Insufficient documentation of combat action.”

Translation:

We cannot reward something that makes our doctrine look outdated.

Bartlett didn’t care.

“Did it work?” he asked Hayes.

“Yes.”

“That’s enough.”

The Army never officially recognized the hay bale gambit.

But special forces instructors years later taught its principles under sterile terms:

Environmental psychology application.

Multi-position acoustic deception.

Low-signature non-kinetic capture techniques.

No one called it what it was:

A farm kid using livestock logic to outthink a war machine.

THE MAN WHO WENT HOME

Tommy Bartlett survived Holland, the Ardennes, and Germany.

He returned to Iowa in 1945 at age twenty-one.

His father met him at the station.

They shook hands.

Said little.

He went back to farming.

He married in 1947, raised three children, expanded the family acreage from 340 to 520.

He never told them the hay bale story.

When asked about the war, he said only:

“I did my job. I came home. That’s enough.”

Every September 18, he received a phone call from Eddie Sullivan. The two men exchanged ten minutes of conversation about crops, weather, baseball, nothing of importance—and everything that mattered.

We survived.

We remember.

We’re grateful.

Bartlett died in 1987 at age sixty-three.

His obituary devoted one line to the war:

“Veteran, 101st Airborne Division, served with distinction.”

LEGACY OF A HAY BALE

In 2007, Dr. Sarah Kendrick, researching unconventional tactics during Market Garden, rediscovered Bartlett in battalion archives. Her academic paper estimated his methods helped prevent sixty to one hundred twenty American casualties.

It gained little attention—eight hundred views its first year.

But among military historians, Bartlett became an emblem of a truth rarely acknowledged in doctrine:

Innovation in war usually comes from privates, not generals.

From farm boys, not tacticians.

From observation, not orders.

Bartlett’s hay bale gambit worked because:

– he understood exhaustion

– he understood fear

– he understood submission reflexes

– he understood terrain

– he understood timing

– he understood people

Because he had spent eighteen years watching cows behave the way soldiers behave under stress.

Because he saw patterns, not chaos.

Because he refused to treat war like the manual said it should be fought.

He treated it like a field on his father’s farm—full of risks, responsive to psychology, and solvable through quiet ingenuity rather than loud bravery.

Thirty-four German soldiers surrendered to a single man armed with a white flag, a rifle he never fired, and the wisdom of a hayfield in Iowa.

He wasn’t the strongest.

He wasn’t the bravest.

He wasn’t the fastest.

He was the smartest.

And in war, that is often enough.

News

“Please Marry Me”, Billionaire Single Mom Begs A Homeless Man, What He Asked In Return Shocked…

The crowd outside the Super Save Supermarket stood frozen like mannequins. A Bentley Sleek had just pulled up on the…

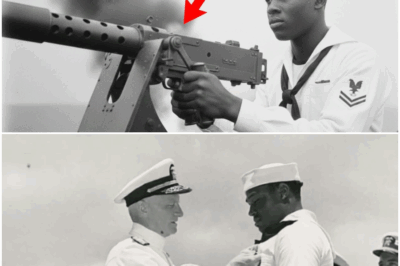

How One Black Cook’s “ILLEGAL” AA-Gun Grab Shook Pearl Harbor — And Forced the Navy to Change

On the morning of December 7, 1941, Pearl Harbor looked like a postcard. The water inside the harbor was calm…

She Was Serving Coffee in the Briefing Room — Then the Admiral Used Her Call Sign and the Room Froze….

She Was Serving Coffee in the Briefing Room — Then the Admiral Used Her Call Sign and the Room Froze…….

Japanese Couldn’t Hit This “Slow” Bomber — The Pilot Shot Down 3 Zeros and Sank Their Carrier

At 7:30 a.m. on May 8, 1942, Lieutenant (junior grade) Stanley “Swede” Vejtasa tightened his harness in the front cockpit…

At two in the morning, my phone buzzed with a message from my son: “Mom… I know you bought this house for ten million, but my mother-in-law doesn’t want you at the baby’s birthday.” I stared at the message for a long time. Finally, I responded: “I understand.” But that night, something inside me shifted. I knew I had put up with enough. I got up, opened the safe, and retrieved the set of documents I had kept hidden for three years. Then, I took the final step. By the time the sun rose… everyone was in shock—and my son was the most shocked of all…

At two o’clock in the morning, the blue glow of her phone dragged Helen Walker out of sleep. The room…

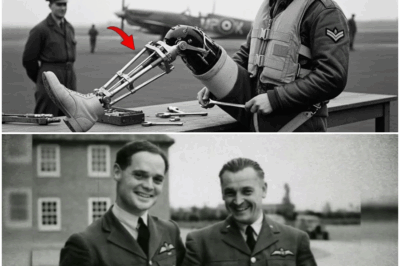

Germans Laughed at This ‘Legless Pilot’ — Until He Destroyed 21 of Their Fighters

At 7:45 on the morning of June 1, 1940, a Hawker Hurricane sliced through the thin coastal haze above Dunkirk….

End of content

No more pages to load