On the morning of December 7, 1941, Pearl Harbor looked like a postcard.

The water inside the harbor was calm and bright under the Hawaiian sun. Along Battleship Row, seven American battleships sat moored in a straight, imposing line, their gray hulls mirrored in the blue. Sailors moved about the decks in routine choreographies—painting, washing down, preparing breakfast. It looked like a scene of overwhelming American power at peace.

Hidden under that tranquility, though, was a set of rules that said not everyone in uniform was really a sailor.

For one 22-year-old on board the battleship USS West Virginia, those rules were carved into his job title. His name was Doris “Dorie” Miller.

He was strong enough to be a heavyweight boxer, brave enough to become one of the most famous heroes of World War II—and officially, the Navy said his job was to haul laundry and pour coffee.

Those rules were about to collide with reality at 7:57 a.m.

A Sailor the Navy Refused to Call a Sailor

Dorie Miller was born in 1919 in Waco, Texas, the third of four sons in a family that made its living farming. He was big from an early age—athletic, quiet, and serious. In high school he played football, but the Depression didn’t leave many opportunities for a Black teenager in central Texas. When he turned twenty, he looked to the military as a way to help his family and see the world.Wikipedia+1

There was a catch. In 1939, the segregated U.S. Navy allowed Black men to enlist only in the steward’s branch—jobs labeled as “mess attendant” or “steward’s mate.” Those positions were not combat roles. They were service roles: cooking, cleaning, serving food, making beds, shining shoes.

It didn’t matter how strong you were or how smart you were; if you were Black, the Navy saw you as support staff.

Miller enlisted anyway. He needed the paycheck. The rating on his enlistment papers read:

Mess Attendant, Third Class.

Basic training didn’t change that. After finishing at Norfolk, he was assigned first to an ammunition ship and then, in early 1940, to the battleship USS West Virginia—a 32,000-ton Colorado-class battleship that would become his home.Wikipedia

On board, the crew quickly learned two things about him. First, he was dependable. Second, he was enormous. At over six feet tall and powerfully built, he didn’t just look like a boxer—he became one, winning the ship’s heavyweight boxing championship.

The “fighter” part of him, though, had no official outlet. Under Navy policy, there were no Black gunners, no Black signalmen, no Black machinist’s mates. On paper, Miller’s job in a war would be exactly the same as his job in peace: cook, carry, and clean.

If enemy planes ever appeared over Pearl Harbor, the Browning .50-caliber anti-aircraft guns bolted to West Virginia’s deck were off limits to him. He wasn’t even supposed to touch them.

Those rules stayed intact right up until the moment the first Japanese torpedo slammed into the ship.

“This Is Not a Drill”

December 7, 1941 began like any other Sunday.

Miller had been up early serving breakfast to the white officers. After the meal, he went below decks to collect laundry—part of the routine that kept the ship running but that few people ever thought about.

At 7:57 a.m., the first explosions hit West Virginia. Japanese torpedo planes had swept in low over the water and loosed a string of Type 91 aerial torpedoes at Battleship Row. At least two slammed into West Virginia’s port side almost back-to-back. The ship lurched violently. Lights flickered. The “general quarters” alarm howled through the corridors.Wikipedia+1

Miller’s assigned battle station was an ammunition magazine for an anti-aircraft battery amidships. When he fought his way through the confusion to reach it, he discovered it had already been destroyed.

With his station gone, he did what good sailors do in a crisis: he reported for more orders.

He headed toward “Times Square,” a central passageway intersection on the ship where sailors without a station to go to could be reassigned. All around him, the ship was absorbing punishment—more torpedoes, bombs from high-level bombers, strafing runs from fighters.

On the way, he began helping carry wounded sailors to safer spots. Smoke filled the compartments. Voices shouted in the semi-darkness. Some of the men he helped wouldn’t live to see the sun go down.

When he reached the topside area near the bridge, an officer spotted him—Lieutenant Commander Doir Johnson, the ship’s communications officer. Johnson saw a massive young sailor looking for something to do and immediately had an idea.

The ship’s commanding officer, Captain Mervyn Bennion, had been hit.

Johnson needed help.

He ordered Miller to come with him.

Carrying the Captain

The bridge of West Virginia was a nightmare.

Bombs had exploded nearby. Shrapnel and fragments had torn through open hatches and windows. Captain Bennion had been struck in the abdomen by a piece of metal that ripped open an artery. It was a wound no ship’s captain ever wants to suffer—a gut shot in the midst of battle, on a ship that itself was already dying.

Even so, Bennion was still trying to command his ship. He was yelling orders, urging his crew to keep fighting, to keep the guns firing, to save West Virginia if they could.

When Miller and Johnson reached him, they saw that the captain was lying in the open, exposed to enemy fire. The bridge itself was being raked by strafing runs. Staying where he was meant certain death in minutes.

Johnson ordered Miller to help move him.

The captain was not a small man. The ship was listing. Fires were burning. Explosions rocked the decks. But Miller’s size and strength—assets that had mostly been used in the ring and in hauling heavy pots and pans—suddenly became critical.

Together with others, he dragged the wounded captain to a more sheltered spot behind the conning tower, where Bennion could at least be protected from direct fire. Miller helped apply pressure to the wound, doing what he could with the limited first aid training messmen received.

It wasn’t enough. The bleeding was too severe.

After a time, Captain Bennion slipped away, dying of his injuries.

Miller had tried to save the man at the very top of a system that did not consider him worthy to stand a watch or man a gun. He had done it instinctively, because the captain was his commanding officer, because they were under attack, and because that’s what you do when someone is bleeding out in front of you.

That alone would have made for a powerful story of courage.

But his day wasn’t over.

A Silent Gun and a Choice

With Bennion gone and the bridge under heavy attack, officers ordered the remaining men to get out while they still could. Fires and flooding were rapidly becoming uncontrollable. Below decks, compartments were filling with water and oil. Black smoke boiled out from ruptured fuel tanks.

On the starboard side, near the bridge, a pair of .50-caliber Browning antiaircraft machine guns sat on a platform that overlooked part of the ship’s perimeter. The guns were meant to throw up a curtain of heavy fire against dive bombers and strafing fighters. Under normal circumstances, they were manned by trained gunners.

On this morning, one of them was unmanned. Its crew had been killed or badly wounded.

The gun sat there idle—belted with ammunition, intact, ready. And useless.

Miller saw it.

According to later accounts, Johnson instructed him first to help feed ammunition to a different gun, which Miller did. Then another officer—either Johnson or an ensign who happened onto the scene—told him to take over that silent .50-caliber mount. Another version has Miller simply moving to the gun on his own initiative when he realized no one else was there to fire it. Different witnesses remembered the order differently. What’s consistent in every telling is what happened next: a mess attendant with no formal gunnery training climbed behind a weapon the Navy had never intended him to touch.

Those were the rules.

And the rules, in that moment, were irrelevant.

The enemy wasn’t checking job descriptions. Japanese pilots diving on West Virginia didn’t care who was supposed to be allowed to shoot back. They cared about turning the battleship into a burning wreck.

Miller swung the Browning’s heavy grips into position. He had watched other sailors use the gun during drills. He knew how the belts fed. He’d seen the basic aiming motions. He understood the concept of leading a target.

He squeezed the triggers.

The gun thundered to life.

Firing Back

On deck level, a .50-caliber machine gun feels less like a weapon and more like a living thing. The barrels pulse. The mounts vibrate. Hot brass rains down in a clinking shower. Each bullet is the size of a man’s finger and leaves the barrel at over 800 yards per second.

Miller’s first bursts weren’t the calm, measured shots of a polished fire control team. They were the urgent firing of a man who’d just watched his captain die, who’d dragged wounded men through burning corridors, and who now saw enemy planes bearing down on his ship.

He fired in short bursts, tracking the silhouettes of Japanese aircraft against the sky, the smoke, and the flames rising from other ships.

Later, Navy records would officially credit him with shooting down at least one enemy plane, and possibly more; eyewitness accounts from that day suggest numbers from two to four. Miller himself later guessed he’d hit “maybe two” before he was ordered to stop.Wikipedia

In a sense, the exact number doesn’t matter.

What matters is that in an era when Black sailors were told they could not be trusted with weapons, he was the one behind the trigger, filling the air with tracers, doing his best to keep more bombs from landing on West Virginia.

For as long as the gun would fire—until the ammo ran out or power to the mount failed—he stayed at it, his huge frame hunched over the weapon, silhouetted against the burning harbor.

When he was finally ordered to leave his position, the sight around him was apocalyptic. West Virginia had taken up to nine torpedoes and two bombs. She was badly on fire and settling to the bottom. Nearby, USS Arizona was a fractured, smoldering ruin after a magazine explosion had torn her apart. USS Oklahoma had capsized. Smoke darkened the sky over the entire harbor.

With the order to abandon ship, Miller joined the stream of battered, oil-soaked survivors making their way off West Virginia.

He went over the side into water slick with burning fuel. A strong swimmer, he managed to reach Ford Island, where he hauled himself onto shore—exhausted, filthy, and alive.

Out of a crew of about 1,500, approximately 130 men from West Virginia were killed that day. Miller was one of the roughly 1,200 who survived.

He had started the morning collecting laundry.

By the time the firing stopped, he had tried to save his captain’s life and fought back with one of the ship’s guns.

From Anonymous “Negro Messman” to National Hero

In the days immediately after Pearl Harbor, the U.S. Navy and the country at large were reeling. Battleships lay sunk or crippled. More than 2,400 Americans were dead. The Pacific Fleet, the pride of American sea power, looked shattered.

At the same time, stories started to circulate—stories of men who had done extraordinary things amid the chaos.

One of those stories, told by other West Virginia crewmen, was about a big Black mess attendant who had hauled wounded men to safety and then manned a machine gun, shooting at Japanese planes until he was ordered to stop.

At first, newspapers mentioned him without a name, calling him simply an unnamed “Negro messman.” But even anonymous, his story resonated. Here was a man who had been trusted only with mops and coffee pots, stepping up to fight when it counted.Wikipedia

Black newspapers and civil rights organizations seized on the story. They understood its significance immediately: in the Navy’s own telling, a Black man had done exactly what the Navy’s rules said Black men were unfit to do.

The Pittsburgh Courier, one of the most influential Black papers in the country, began campaigning for this hero—still unnamed—to be identified and properly honored. The NAACP, the National Negro Congress, and other groups joined in. They wrote letters. They passed resolutions. They urged readers to contact members of Congress.

Pressure built.

Eventually, the Navy released his name: Mess Attendant Second Class Doris “Dorie” Miller.Wikipedia+1

The public now had a face to go with the story.

Recognition, however, did not come easily.

The Secretary of the Navy, Frank Knox, was known to oppose placing Black sailors in combat roles. Behind the scenes, he pushed back against recommendations that Miller be given the Medal of Honor. No Black service member would receive that highest decoration for World War II service until decades later.Wikipedia

But the combination of eyewitness testimony, public pressure, and the symbolic power of the story made it impossible for the Navy to simply pat him on the back and move on.

President Franklin D. Roosevelt approved the award of the Navy Cross—the Navy’s second-highest decoration for valor at the time—to Dorie Miller.

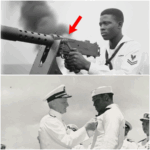

On May 27, 1942, aboard the aircraft carrier USS Enterprise at Pearl Harbor, Admiral Chester W. Nimitz, Commander in Chief of the Pacific Fleet, pinned the Navy Cross on Miller’s chest.history.navy.mil+1

Nimitz’s words at the ceremony carried extra weight:

“This marks the first time in this conflict that such high tribute has been made in the Pacific Fleet to a member of his race.”

In that moment, standing ramrod straight in his dress whites, Miller became the first African American in history to receive the Navy Cross.

Photos from the ceremony show him looking serious, almost solemn. He wasn’t a polished public speaker. He didn’t give dramatic speeches. He was, by all accounts, a quiet man.

The image spoke for him.

Here was a Black cook being honored by a four-star admiral for doing what the Navy had refused to train him to do.

A Symbol in Uniform

After the decoration, the Navy brought Miller back to the mainland for a war bond tour. He traveled the country, speaking at rallies, standing on stages as crowds cheered, and posing for posters that urged Americans to “Remember Pearl Harbor” and buy bonds.

His presence electrified Black communities. Here, finally, was official acknowledgment that Black Americans were not just laborers in uniform—they were fighters. His story turned into poems, songs, and sermons. Civil rights leaders pointed to him as proof that Black citizens were ready to fight and die for a country that still treated them as second-class.

At the same time, the Navy’s policies didn’t change overnight.

Despite the medal and the publicity, Miller remained in the steward’s branch. His rating eventually changed from mess attendant to ship’s cook, petty officer third class, but his basic duties stayed the same. The combat arms were still mostly closed to Black sailors.Wikipedia

In 1943, after his bond tour, Miller requested to go back to sea. The Navy assigned him to USS Liscome Bay, a brand-new escort carrier built on a small merchant-hull design. Escort carriers were not as glamorous as fleet carriers, but they were crucial—providing air cover for amphibious invasions and convoys.

Liscome Bay joined operations in the Central Pacific and, in November 1943, supported the invasion of the Gilbert Islands, including the Battle of Makin.Wikipedia+1

Miller did his job, just as he always had—serving food, keeping things running, carrying with him the stories and scars of Pearl Harbor.

Liscome Bay and the Last Alarm

Just before dawn on November 24, 1943, Liscome Bay was operating near Makin Atoll. The invasion was essentially over; U.S. troops had captured the island, and the carrier was part of a task group providing cover as forces consolidated.

Below the surface, Japanese submarine I-175 was stalking the formation.

At about 5:10 a.m., the submarine fired four torpedoes. One struck Liscome Bay on the starboard side, right near the ship’s bomb magazine. The result was catastrophic.Wikipedia+1

The explosion ripped the ship apart from the inside. A pillar of flame shot into the pre-dawn sky. Men were blown overboard. Fires spread almost instantly. There was no time for an organized, prolonged fight to save the ship. Liscome Bay sank in about twenty-three minutes.

More than 600 of the roughly 900 men aboard were killed. It was the deadliest escort-carrier loss of the war for the U.S. Navy.

Among the dead was Cook Third Class Doris “Dorie” Miller. His body was never recovered.

Just two years after he’d stood on the deck of Enterprise wearing his Navy Cross, the man whose courage had captivated a nation disappeared beneath the Pacific, one more name on a long list of casualties.

He was twenty-four years old.

Breaking the Old Rules

Dorie Miller did not live to see the changes his actions helped set in motion.

During the war, Black Americans continued to face segregation, discrimination, and limited roles in all branches of the military. But as the conflict dragged on, the country’s need for manpower and the undeniable performance of Black units and individuals started to erode resistance to change.

The logic was simple and powerful: if Black Americans could die at Pearl Harbor, in Italy, in the Pacific, and in the skies over Europe, they were entitled to full citizenship and equal opportunity.

Miller’s story became one of the most potent arguments. Segregation wasn’t just immoral; it was inefficient. It kept proven fighters away from the very jobs the nation most desperately needed done.

After the war, President Harry S. Truman took a decisive step. In 1948, he signed Executive Order 9981, directing the armed forces to desegregate and guaranteeing “equality of treatment and opportunity for all persons in the armed services without regard to race, color, religion or national origin.”Encyclopedia Britannica

Desegregation didn’t happen overnight. There were years of resistance and half-measures. But the legal barrier that had kept men like Dorie Miller confined to galleys and wardrooms had been formally struck down.

The Navy slowly opened up ratings. Black sailors became gunners, machinists, pilots, and officers. The steward’s branch, once almost entirely Black, diversified and eventually was eliminated as a racially defined track.

In the decades that followed, the Navy and the wider country found many ways to remember Miller.

Schools, streets, and parks were named after him. A Knox-class frigate, USS Miller (FF-1091), entered service in the 1970s bearing his name. The U.S. Postal Service honored him with a commemorative stamp in 2010.Wikipedia+1

But in 2020, nearly eighty years after Pearl Harbor, the Navy announced a tribute that would have been unimaginable in 1941.

USS Doris Miller: A New Name on a New Carrier

On January 20, 2020, at a Martin Luther King Jr. Day ceremony at Pearl Harbor, Acting Secretary of the Navy Thomas B. Modly announced that CVN-81, the fourth ship in the new Gerald R. Ford–class of nuclear-powered aircraft carriers, would be named USS Doris Miller.Wikipedia+1

It was a historic choice.

Doris Miller will be the first aircraft carrier in U.S. history named for an enlisted sailor rather than an admiral, president, or state—and the first carrier named for an African American.

The ship will displace about 100,000 tons, stretch more than 1,000 feet, and carry an air wing of advanced fighters, electronic warfare aircraft, helicopters, and drones. It will be one of the most complex machines ever built by human beings, a floating city and airbase capable of projecting American power across the globe for half a century.Wikipedia+1

And across its stern, in letters taller than Dorie Miller himself, will be his name.

A man who once had to break the rules just to touch a .50-caliber gun will have his name on the hull of a ship bristling with jet aircraft and guided missiles.

The symbolism is obvious—and appropriate.

Where the Navy once told Black sailors, “You can serve, but only in the kitchen,” it now tells every sailor who walks up the brow onto CVN-81: “You are serving on a ship named for a Black enlisted man who proved, beyond question, that courage and ability are not limited by race or rating.”

Why Dorie Miller Still Matters

When you strip away the ceremony and the symbolism, what remains about Dorie Miller’s story is something simple and human.

On the worst day of his life, when the world around him was literally exploding, he did three things:

He went where he was needed. His own battle station was gone, so he looked for another job and started helping the wounded.

He tried to save a life. He risked himself to drag his critically wounded captain to shelter and applied what little medical aid he could.

He fought back. He stepped behind a weapon he’d never been allowed to train on and used it to defend his ship and his shipmates.

None of that required a particular race or job title.

All of it required courage, initiative, and a willingness to put the mission and the people around him ahead of his own safety.

Those are the qualities Americans like to think of when we talk about our best selves.

At Pearl Harbor, they came from a sailor who wasn’t even allowed to be called a sailor in the full sense of the word.

It is tempting, in hindsight, to treat his story solely as a triumph—a tale of injustice answered and wrongs eventually righted. But it’s also a reminder of how long it can take institutions to live up to their ideals, and how many people have to push and bleed and sometimes die before change comes.

Dorie Miller did not set out to be a civil rights icon. He never held a protest sign. He never gave a fiery speech. He simply did his duty as he understood it on a morning when doing so meant standing in front of bullets.

The Navy of 1941 made him a cook.

History made him something much larger.

As long as his name sails on the side of a supercarrier and echoes in the halls of American memory, he will stand as proof of a hard but hopeful truth:

Rules can be wrong.

Courage can expose that.

And sometimes, one person’s willingness to grab the gun no one thinks they’re allowed to touch can help a great nation take a step closer to being worthy of the flag painted on its hull.

News

“Please Marry Me”, Billionaire Single Mom Begs A Homeless Man, What He Asked In Return Shocked…

The crowd outside the Super Save Supermarket stood frozen like mannequins. A Bentley Sleek had just pulled up on the…

She Was Serving Coffee in the Briefing Room — Then the Admiral Used Her Call Sign and the Room Froze….

She Was Serving Coffee in the Briefing Room — Then the Admiral Used Her Call Sign and the Room Froze…….

Japanese Couldn’t Hit This “Slow” Bomber — The Pilot Shot Down 3 Zeros and Sank Their Carrier

At 7:30 a.m. on May 8, 1942, Lieutenant (junior grade) Stanley “Swede” Vejtasa tightened his harness in the front cockpit…

At two in the morning, my phone buzzed with a message from my son: “Mom… I know you bought this house for ten million, but my mother-in-law doesn’t want you at the baby’s birthday.” I stared at the message for a long time. Finally, I responded: “I understand.” But that night, something inside me shifted. I knew I had put up with enough. I got up, opened the safe, and retrieved the set of documents I had kept hidden for three years. Then, I took the final step. By the time the sun rose… everyone was in shock—and my son was the most shocked of all…

At two o’clock in the morning, the blue glow of her phone dragged Helen Walker out of sleep. The room…

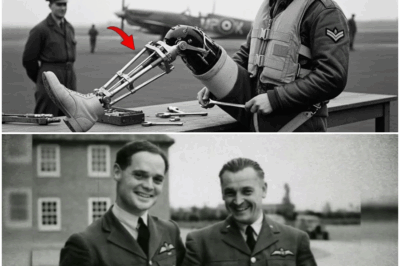

Germans Laughed at This ‘Legless Pilot’ — Until He Destroyed 21 of Their Fighters

At 7:45 on the morning of June 1, 1940, a Hawker Hurricane sliced through the thin coastal haze above Dunkirk….

We.Can’t Remove Our Uniforms What the American Guards Did Next Left the German Women POWs Speechless

On a gray February morning in 1945, in a field of half-frozen mud outside the shattered outskirts of Cologne, a…

End of content

No more pages to load