On the afternoon of February 10, 1945, high above the Philippine Sea, Lieutenant Lewis Curtis stared down from the cockpit of his P-51D Mustang and saw two things no fighter pilot ever wants to see at the same time:

A friendly pilot bobbing in a life raft.

And another friendly aircraft lined up to land on a Japanese airfield.

Curtis had about twenty minutes of fuel left, a sky turning orange with the setting sun, and a decision to make that no training manual had ever covered.

By the time it was over, he would become the only American pilot officially credited with shooting down an American aircraft on purpose—and given a medal for it.

A Mission That Was Supposed to Be Routine

It started as just another long-range fighter sweep.

Curtis was flying with the 3rd Air Commando Group, operating P-51 Mustangs out of the Philippines. The group’s job was to escort bombers, hit Japanese airfields, and scout for trouble as General Douglas MacArthur’s forces fought their way back up through the islands.

On February 10, Curtis and his wingman, Lieutenant Bob LaCroix, had been assigned a mission over Batan Island, a small, Japanese-held speck north of Luzon that housed a coastal airstrip and anti-aircraft positions. Their job: silence enemy air activity and harass anything that moved.

They did it well.

By late afternoon, the two Mustangs had:

Shot down two Japanese fighters in the air,

Destroyed three more aircraft on the ground, and

Drawn enough anti-aircraft fire to convince anyone watching that the island was very much still a combat zone.

Then a flak burst caught LaCroix’s P-51 full in the belly.

Shrapnel blew through his engine. Coolant and oil exploded into a white cloud. LaCroix managed to coax the crippled Mustang out over the water before bailing out. His parachute blossomed, and he dropped into the sea about fifty yards off Batan’s shore.

He survived the ejection. The raft deployed. He crawled in.

He was now a lone American pilot floating within easy range of an island full of Japanese troops.

Curtis circled above, watching him, suppressing the urge to scream at the distance that separated them. This was enemy water. There would be no quick pickup. On the radio, he called in LaCroix’s position and requested a PBY Catalina rescue plane for dawn.

Then he looked at his fuel gauge.

Twenty minutes left, maybe less. The sun was already brushing the western horizon.

He still hadn’t seen the last crisis of the day.

The C-47 That Didn’t Know Where It Was

As Curtis orbited, scanning for Japanese boats or more enemy aircraft, he saw something unexpected at the edge of the sky: a twin-engine transport slipping in from the east, low and slow, with landing gear down and flaps extended.

It was on final approach to Batan Island.

At first, Curtis assumed it had to be Japanese. The island was under enemy control; no American crew would be crazy enough to try to land there.

But as the newcomer rolled closer in the late-day light, details resolved through the haze.

He saw the markings.

White stars on blue. U.S. Army Air Forces insignia.

On the tail, the numbers identified it as a C-47 Skytrain from the 39th Troop Carrier Squadron, known as the “Jungle Skippers.”

This wasn’t a captured plane with fake markings.

This was an American transport ship on approach to an enemy runway.

Curtis’s stomach dropped.

He grabbed his radio handset and broadcast an urgent warning:

“C-47, C-47 on final—this is Bad Angel. You’re approaching a Japanese–held island. Wave off immediately. I say again, wave off!”

Static hissed. No reply.

He tried again.

Nothing.

The C-47 continued its descent, lined up perfectly with the Japanese-controlled runway, so perfectly that any flak gunner on that island would have been setting up for a welcoming barrage.

Curtis remembered all too well what Japanese captivity meant.

He’d had his own taste of being a prisoner, and that knowledge was about to drive him into one of the most agonizing choices of his life.

A Pilot Who Already Knew What Capture Meant

Lewis Curtis was no untried rookie.

By the time he found himself above Batan, he was 25 years old and already a decorated combat veteran from another theater of the war entirely.

He’d first seen action in North Africa and Italy, flying P-38 Lightnings with the 82nd Fighter Group. He’d earned kills against the Luftwaffe and the Regia Aeronautica, taking down German and Italian fighters in combat over the Mediterranean.

In August 1943, during the Salerno campaign, Curtis broke formation to save another pilot under attack by German Messerschmitts. He shot down two Bf-109s. He also took enough damage that both his engines failed.

He crash-landed on a hostile beach.

Italian troops captured him.

The POW camp near Rome taught him what being “out of the fight” really meant: forced marches, interrogations, fear, hunger, and the dread of not knowing what would happen next. When Italy surrendered in September 1943 and German forces prepared to take over the camps, Curtis and four other Americans stole a boat in a desperate attempt to reach Allied lines.

They were recaptured, then escaped again just before the Germans took control.

He spent months hiding in occupied territory, moving by night, depending on civilians for help, before finally reaching friendly forces.

Most shot-down pilots who survived that experience were done with combat. The Army Air Forces usually sent them home, both for their safety and because international law frowned on sending escapees right back into the same theater.

Curtis did something different.

He volunteered to return to combat. Because he wasn’t allowed to go back to Europe, the Army shipped him to the Pacific in August 1944, where he transitioned to the P-51 Mustang and joined the 3rd Air Commando Group.

Three days before the incident over Batan, Curtis had shot down a Japanese Ki-46 reconnaissance aircraft near Formosa (Taiwan), adding a rising sun to the scoreboard he’d already started with German and Italian insignia.

That made him one of very few American pilots with victims from all three Axis powers.

Now, as he stared at that descending C-47, he was about to face a fourth flag.

“They Won’t Take Prisoners”

The C-47 thundered closer to Batan, wings steady, tailwheel down.

At 500 feet, it was committed. There was no more leeway for a casual course change. To land safely, a transport of that size needs time to adjust flap settings and throttle and angle; you don’t just yank it around and head out to sea again at the last second.

Curtis could see into the cockpit now. Two pilots hunched over their controls, focused on their instruments and the patch of open earth in front of them.

Not one of them glanced at the P-51 flying just 30 feet off their wing, wagging his wings in a frantic signal to break off.

They had no idea any of this was wrong.

Somewhere in the confusion of Pacific weather, bad maps, and malfunctioning radios, the C-47’s crew had become lost. Their radio wasn’t receiving. They’d likely been flying blind for hours, fuel dwindling, looking desperately for anywhere to put down.

Then they’d seen an island with a strip.

In their minds, that strip was salvation.

In reality, it was a trap.

Curtis knew what the Japanese did to captured aircrews—especially those who’d strafed their installations. He also knew that two Army nurses were reported missing in the area, ferrying between bases. If they were on that transport and it touched down at Batan, he didn’t have to imagine what would happen. Filipino guerrillas, escaped POWs, and his own experience made the picture all too vivid.

Capture didn’t mean sitting out the rest of the war in a camp trading cigarettes and stories. It meant interrogations, starvation, beatings. For women, it meant worse.

He keyed his radio again, shouted another warning into the static, felt the seconds skating away.

“C-47, wave off! Wave off!”

Nothing.

The transport kept coming.

The altimeter needle in Curtis’s cockpit said the C-47 was at roughly 300 feet now. Maybe 15–20 seconds from wheels-down.

Above, Japanese anti-aircraft crews were tracking both aircraft, just waiting for the transport to enter their kill zone.

Lewis Curtis understood, in a flash of cold certainty, that doing nothing here would mean those Americans died badly.

He rolled hard and dove behind the C-47, knowing this was about to become the most controversial trigger pull of his life.

Precision Under Fire

He had one advantage: the P-51 Mustang was one of the finest gun platforms ever put in the sky.

Curtis’s aircraft—named Bad Angel—carried six .50-caliber Browning machine guns, three in each wing, firing at a combined rate of roughly 70 rounds per second. At the right range, a one-second burst could shred a fighter.

But the C-47 wasn’t an enemy fighter.

It was a friendly transport loaded with twelve Americans, including two flight nurses. The goal wasn’t to kill anyone on board.

The goal was to force the pilot to ditch in the ocean instead of landing at that airfield.

That meant he had to be both aggressive and surgical: disable both engines, without hitting the fuselage, before the C-47 could roll onto Batan’s runway.

There were maybe 10–12 seconds left.

Curtis dove, pulled into level flight behind the C-47 at about 50 yards—dangerously close at that speed. He lined up on the right engine.

He thumbed the gun button.

The Mustang shuddered as all six guns opened up. Bright tracers converged on the starboard engine nacelle. Metal blossomed as rounds tore through the cowling. Flames burst from the engine. The propeller slowed, bent, stopped.

The C-47 lurched sideways. Its pilots reacted instantly—fighting asymmetric thrust, adding power to the left engine, banking hard to keep the aircraft from rolling.

But the C-47 was built to fly on one engine.

It kept going. Still descending. Still pointed at the runway.

Japanese anti-aircraft guns began to fire in earnest now. Tracer lines stitched the sky. 20mm shells burst close enough to rock Curtis’s Mustang.

He ignored them.

He yanked Bad Angel back into position and slid over to line up on the left engine.

Altitude: roughly 100 feet.

Time to touchdown: less than 10 seconds.

He squeezed the trigger again.

Another long, brutal burst. Tracers hammered into the left engine. The propeller exploded backward, pieces spinning away into the air. The engine cowling opened like a peeled can. Black smoke poured out.

The C-47 now had no power at all.

In the cockpit, the transports’ pilots had a fraction of a second to curse and then do the only thing left: haul back gently on the yoke, flare as much as they could, and put the big bird into the water.

They ditched just beyond the surf line, in deep water, away from reefs.

The C-47’s belly hit the ocean, threw up a sheet of spray, skipped, slammed again, then settled in, front end dipping, tail rising as it rapidly lost momentum.

Amazingly, there was no explosion.

No fireball. No breakup of the fuselage.

Within minutes, Curtis saw shapes clambering onto the wings, then into life rafts.

Twelve Americans—shaken, soaked, but alive—were now floating offshore in the same perilous water as LaCroix had been.

Curtis saw Japanese soldiers scrambling on the beach below. He dropped low and raked the shoreline with one more strafing run, driving them into trenches and behind palm trees just long enough to buy a little time.

Then he checked his fuel gauge.

He was down to fumes.

Two Rafts, Not One

As the tropical dusk deepened, Curtis now had two separate groups of Americans in rafts off a Japanese-held island:

LaCroix, his wingman,

And the twelve people from the C-47.

He climbed as high as he dared on the remaining fuel, relayed the updated situation by radio—coordinates, number of rafts, estimated distance from shore—and begged for a PBY Catalina at first light.

Then he stayed until staying any longer would mean joining them in the water.

He made low, harassing passes when Japanese boats tried to sneak out. Each time, the whine of the P-51 sent them turning back toward shore. Eventually, in the full dark, he couldn’t tell friend from foe.

At “bingo fuel”—the point where he needed to leave or risk crashing himself—Curtis dipped his wings in a brief, sorrowful salute and turned for home.

He landed at Mangaldan Airfield with his fuel gauge reading empty.

Then came the debrief.

“You Shot Down What?”

Back on the ground, Curtis sat in a tent and walked his commander through every detail:

The rescue circle over LaCroix,

The unexpected appearance of the C-47,

The lack of radio response,

The failed visual warnings,

The decision to shoot out both engines,

The ditching,

The rafts.

His squadron commander listened carefully. Then he made a call up the chain to General George C. Kenney, commanding general of Allied Air Forces in the Southwest Pacific.

Kenney wanted a full explanation.

Putting bullets into a U.S. aircraft—even with the best intentions—was not something that happened every day.

What Curtis didn’t know yet was what had happened inside the C-47.

Inside the Skytrain

The C-47 had left Leyte bound for Manila, carrying a mixed load of crew and passengers:

Four crew members,

Eight passengers,

Including two Army nurses.

The weather had been bad. Storm clouds, shifting winds, and a malfunctioning radio combined to knock them far off course. After five hours in the air with no solid navigational fix, low on fuel and unable to raise anyone on the radio, the pilot finally descended below the clouds, desperate for a visual landmark.

He saw an island. He saw an airstrip.

He saw salvation.

He did not know it was Batan Island, in Japanese hands.

When the Mustang appeared on his wing, the pilot assumed it was a friendly escort. When it wagged its wings, he thought little of it—just another fighter telling him “I see you.”

Then the P-51 dropped behind him.

And hell broke loose.

From the cockpit crew’s perspective, the attack was shocking and infuriating. Their aircraft jolted as the right engine erupted in flame. Seconds later, the left engine disintegrated.

They were convinced they’d been hit by friendly fire from a madman.

Still, the ditching went well. They evacuated into life rafts in textbook fashion. They spent a long, terrifying night in shark-infested waters watching Japanese searchlights sweep the shoreline and boats venture out before turning back under P-51 fire.

In the dark, one of the rafts paddled over.

It carried Bob LaCroix.

He told them where they were.

He told them what that airstrip was.

He told them that the “crazy” fighter pilot had actually saved their lives by forcing them to ditch rather than land.

Anger turned to shock.

Then gratitude.

Especially for one young nurse.

The Woman on the Manifest

The next morning, just before sunrise, four Mustangs and a PBY Catalina took off. Curtis, having slept little if at all, led the fighter cover.

They found the rafts where he’d left them, miraculously still afloat and not yet captured. The PBY landed, taxied, and pulled the crews aboard.

Within twenty minutes, all thirteen Americans were back in the air, heading home. Two of them were Army nurses, covered in salt and exhausted but alive.

Curtis landed later that morning, oxygen mask creasing his face, and was told Gen. Kenney wanted to see him.

In the operations tent, Kenney slid a sheet of paper across the table—the passenger manifest from the C-47.

Curtis’s eyes scanned the list.

His heart stopped at one name:

Svetlana Valeria, Army Nurse Corps, age 19.

Two nights earlier, Curtis had taken Svetlana to dinner after a dance on Lingayen. She was a Russian-American, a former aspiring actress before the war, with dark hair and sharp humor. They’d talked about movies, California, and how weird it felt to try and act normal in the middle of a global war.

They’d agreed to meet for dinner again the following week.

He had just shot her airplane out of the sky.

Kenney watched the blood drain from Curtis’s face.

“Did you know she was aboard when you fired?” the general asked.

Curtis shook his head.

“Absolutely not, sir.”

Kenney nodded. That was the answer he expected—and needed. Officially, Curtis had made a tactical judgment based solely on what he saw: an American transport about to land in enemy territory with no radio contact.

“I’m going to say exactly that in my report,” Kenney told him. “You saw an American aircraft about to be captured. You made a decision. You disabled it and saved thirteen lives.”

Then Kenney added something Curtis didn’t expect:

“This isn’t a court-martial, son. It’s a commendation.”

The Medal and the Slap

Curtis swallowed. A commendation?

For shooting down an American airplane?

Kenney was blunt.

“Damn right. You executed one of the most precise, gutsy decisions under pressure I’ve ever heard of. You did more for those people by firing on them than any lawyer in the Pentagon could have.”

He stood.

“Now you still have one more job. You need to go explain all this to Nurse Valeria. Good luck with that, Lieutenant. Dismissed.”

If German flak hadn’t scared Curtis, this did.

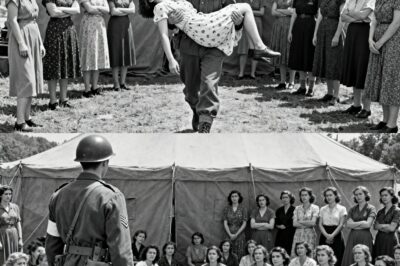

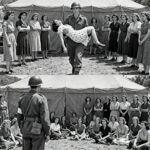

At the field hospital on the edge of the airstrip—a collection of white tents and tired faces—Curtis found Svetlana sitting on a cot, still in a salt-stained uniform, her dark hair pulled back tightly.

When she saw him, she stood.

For a long moment, neither said a word.

Then she walked up and slapped him hard across the face.

“That’s for shooting me down,” she said quietly.

Before he could respond, she grabbed his collar and kissed him.

“And that’s for saving my life.”

Curtis stood there, stunned, his cheek stinging, his brain trying to catch up. Around them, some of the other crew members chuckled. The anger they’d felt in the raft had evaporated once they learned what Batan really was.

Svetlana explained that they’d spent hours in the rafts believing he’d attacked them for no reason, convinced they’d narrowly escaped a crazed friendly pilot. Only when LaCroix paddled over and explained the lay of the land did the truth sink in.

“You had no idea I was on board?” she asked.

“None,” he said. “I just saw Americans about to land on a Japanese runway.”

She nodded slowly.

“Then you made the only decision that made sense.”

She sat back down on the cot and admitted she’d spent half the night composing angry speeches for when she found him.

“I was going to call you every name in the book,” she said. “Then I realized I’d be dead if you hadn’t done what you did.”

“About that dinner next week…” Curtis began awkwardly.

“Most romantic second date in history,” she replied. “We’re absolutely still having it.”

Four Flags on Bad Angel

Stories like this spread quickly in wartime.

Within days, pilots across the Southwest Pacific had heard about the Mustang pilot who shot down a C-47 to save its crew from capture. Within weeks, Air Force Magazine ran a feature story. The legend of “Bad Angel” grew.

On the side of Curtis’s P-51, the crew chief painted kill marks:

Seven swastikas for German aircraft he’d downed over the Mediterranean;

One fasces symbol for an Italian Macchi C.202;

One rising sun for the Japanese Ki-46 he’d dropped near Taiwan;

And now, uniquely, one small American flag—representing the C-47.

It was not a joking “friendly fire” mark. It was an official acknowledgment of a deliberate act, recorded and credited in combat reports.

Lewis Curtis became, as far as the records show, the only American fighter pilot with kills against four different air forces:

The German Luftwaffe,

The Italian Regia Aeronautica,

The Imperial Japanese air arm,

And his own U.S. Army Air Forces.

General Kenney’s commendation recommended an oak leaf cluster to the Distinguished Flying Cross (a second award) for Curtis’s actions that day. The citation cited “extraordinary heroism and quick thinking in preventing the capture of American personnel by enemy forces.”

The accompanying paperwork made it clear: the destruction of the C-47 had been a tactical necessity executed with remarkable precision.

In later years, the scenario would show up in tactical decision games for fighter pilots:

“You are low on fuel, circling a downed wingman off an enemy island. A friendly transport approaches, about to land at the enemy’s field. No radio contact. No time. What do you do?”

There is no neat, regulation answer.

There is only judgment.

Curtis had it.

After the War: A Life Built on Hard Choices

Lewis and Svetlana continued seeing each other throughout the final months of the war. He flew missions; she treated wounded men. They grabbed dinners when they could at dusty forward bases, danced to scratchy records, and built a relationship on a story almost too Hollywood to be believed.

“How did you two meet?” friends would ask.

“He shot me down,” Svetlana would say dryly. “Best first date I ever had.”

The war in the Pacific ended in August 1945 after the atomic bombings of Hiroshima and Nagasaki and Japan’s surrender. Curtis had survived it all:

The Mediterranean front,

Being shot down and captured,

Escaping a POW camp,

100+ combat missions in two theaters,

And the most nerve-wracking trigger pull of his career.

On April 2, 1946, Lewis Curtis and Svetlana Valeria were married in Fort Wayne, Indiana. The wedding was small—family, a few fellow pilots, and a nurse who’d been in the raft that night off Batan, now standing as maid of honor.

The toasts included more than one joke about having to shoot down your bride to get her attention.

After the war, Curtis stayed in uniform. When the U.S. Air Force separated from the Army in 1947, he transferred over and continued his career. He flew C-54 transports during the Berlin Airlift, delivering supplies to a city held hostage by a Soviet blockade. Later, he moved into staff roles.

He retired in 1963 as a lieutenant colonel and went into the construction business in Fort Wayne. He and Svetlana raised two children, Christopher and Valeria Louise. They rode out the Cold War together. They saw men walk on the moon and presidents fall. They watched the country that had sent them to war change in ways neither could have imagined.

Like many veterans of intense combat, Curtis didn’t talk much about the worst days. Every once in a while he’d wake from a nightmare, breathing hard, some old horror from Salerno or New Guinea playing on a loop behind his eyes.

Svetlana understood. She’d been in that water too.

On February 5, 1995, just five days shy of the 50th anniversary of the C-47 incident, Lewis Curtis died at age 75. Svetlana was at his side, holding the hand that had saved her life and changed her future half a century earlier.

She lived until October 2013, passing away at 87.

They spent nearly fifty years together, married because he’d been brave—or reckless—enough to shoot her down.

Bad Angel and the Lesson It Carries

Today, Curtis’s old Mustang, P-51D “Bad Angel,” sits at the Pima Air & Space Museum near Tucson, Arizona.

Visitors wander past rows of warbirds—the sleek F-86 Sabre, the hulking B-52, the delicate fabric-and-wood trainers. When they reach Bad Angel, most notice the paint job first: silver skin, invasion stripes, nose art.

Then they spot the kill marks.

Seven swastikas.

One Italian fasces.

One Japanese rising sun.

And one American flag.

Some of them frown, lean closer, and ask the nearest docent: “Is that real?”

The answer—backed up by combat reports, award citations, photographs, and interviews—is yes.

It really happened.

The panel text talks about Curtis’s unusual record, his kills across three Axis air forces, and his decision over Batan. But it can’t capture the full weight of what that American flag stands for.

It’s not a symbol of friendly fire in chaos.

It’s a symbol of judgment under pressure.

Of understanding that the purpose of all that metal and fuel and training isn’t to preserve airplanes. It’s to save lives and win wars.

Sometimes that means destroying the very thing you’re supposed to protect.

Rules, Principles, and the Hardest Kind of Courage

In war, a lot of energy goes into writing rules:

Don’t fire on friendlies.

Don’t break formation.

Don’t disobey orders.

Don’t take unauthorized actions.

Those rules exist for good reasons. Without them, chaos would reign.

But rules are written for the most common situations. They can’t cover every scenario.

There are moments—rare, terrifying, and lonely—when someone on the scene has to decide whether obeying the rule will violate the principle the rule was meant to serve.

Lewis Curtis faced that kind of moment on February 10, 1945.

The rule said: don’t fire on American planes.

The principle said: don’t let Americans fall into enemy hands if you can possibly prevent it.

He chose the principle.

He accepted that, if he was wrong, he’d be branded a criminal for the rest of his life. He accepted that, even if he was right, some would never understand. He accepted responsibility for a decision no one in a safe office could make for him in those ten seconds.

That’s life-or-death judgment.

That’s leadership.

And that’s why, when you stand in front of Bad Angel and see that little American flag painted between a swastika and a rising sun, you’re not looking at a joke.

You’re looking at a reminder that sometimes doing the right thing looks wrong to everyone who doesn’t know the whole story.

Curtis never called himself a hero. In interviews later, he usually shrugged it off.

“I just did what needed doing,” he’d say.

Maybe that’s the clearest definition of courage there is: not thinking you’re special, not wanting medals, not needing your name in a history book—just recognizing the moment when the easy thing and the right thing diverge, and grabbing the stick anyway.

Off Batan Island in 1945, with fuel running low and the sun going down, Lewis Curtis found that moment and pulled the trigger.

He shot down his own side.

And saved them.

News

When a father returned from his military mission, he never imagined finding his daughter sleeping in the pig sty by order of her stepmother. What happened next left everyone speechless.

When Sergeant Alvaro Cifuentes stepped off the military bus in the small town of Borja , Zaragoza, after nearly ten months deployed on an…

He hit her and laughed as if it meant nothing—until every Marine in the mess hall set down their trays, stood up, and locked their gaze on him…

PART 1: The Laughing Stock “Watch where you’re going, sweetheart.” The voice was thick with unearned confidence. Abigail looked up….

A U.S. soldier brought a starving Japanese female POW into his tent—only to find 200 others waiting outside the next morning…

Henderson stepped into the rain. The wind and its angry water made his sleeves heavy. Men with rifles formed, officers…

I got pregnant in tenth grade. My parents looked at me coldly and said, “You’ve shamed this family. From this moment on, you’re no longer our daughter.” Then they kicked me out, leaving me and my unborn child to survive the night alone. Twenty years later, they showed up wearing strained smiles, holding gifts: “We’d like to meet our grandson.” I led them into the living room. When the door opened, they went completely still. My mother turned white, and my father shook so badly he couldn’t get a single word out…

I got pregnant in tenth grade. My parents looked at me coldly and said, “You’ve shamed this family. From this…

The day before my brother’s wedding, my mom cut holes in all my clothes, saying, “This will suit you better.” My aunt laughed, adding, “Maybe now you’ll find a date.” But when my secret billionaire husband arrived, everyone’s faces went pale…

The Silent Investor Chapter 1: The Art of the Cut “You’re not wearing that to the rehearsal dinner, are you?” My mother’s…

After my daughter screamed “You’re not family!” because of a spilled drink, I walked out quietly and told her, “You’ll remember this day.” I spent ten days changing my will and my life. Then she called, voice shaking, realizing she’d gone too far.

My name is Eleanor Whitman, and for almost two years, every Sunday at noon, I brought homemade food to my…

End of content

No more pages to load