On a quiet Saturday afternoon in downtown Chicago, Detective Rebecca Walsh walked into Murphy’s Antiques with one simple goal: find a quirky, meaningful birthday gift for her mom.

She left with a 1912 wedding photograph, a cold case that spanned eight cities and seven years, and the image of one of the most chilling serial killers the Midwest had never known.

This is the story of how a single wedding portrait—one in which you couldn’t even see the bride’s face—ended up solving a century-old string of murders.

1. The Bride Who Refused to Show Her Face

Murphy’s Antiques sits on a narrow side street near the Chicago River, squeezed between a coffee shop and a pawn broker. Inside, the air smells like old paper, lemon polish, and dust. The owner, Patrick Murphy, is the kind of man who seems born to stand behind a wooden counter, cataloging the past.

Rebecca headed straight for the back, where Murphy kept boxes of old photographs and studio portraits—soldiers in uniform, stiff families in dark clothing, couples on their wedding day staring solemnly into the camera.

Her mother loved this kind of thing: sepia-toned glimpses into the lives of strangers. Usually, Rebecca picked out something charming or sweet—a young soldier holding hands with his sweetheart, a big family squeezed onto a front porch.

This time, the photo that stopped her was anything but sweet.

The groom in the picture looked to be in his early fifties, heavyset, dressed in a dark suit that was expensive even by 1912 standards. He had a thick mustache, carefully groomed, and a confident gaze that met the camera head-on.

The bride stood beside him in an ornate white gown, her posture elegant and assured, her hands folded calmly at her waist.

But her face was completely hidden.

Not partially obscured. Not demurely softened by a thin veil.

Hidden.

An unusually heavy lace veil fell from a crown of flowers and draped down like a curtain over her entire face, so dense that not a single feature was visible. No eyes. No nose. No mouth. Just a pale, lacy wall.

Murphy wandered over and peered at the image with her.

“Strange, huh?” he said. “A wedding photo where you can’t even see the bride. Found it at an estate sale. No names on the back, nothing in the box. Studio stamp just says Harrison Photography, Chicago. Date: June 22, 1912.”

Most brides in that era, even modest ones, lifted their veils for the formal portrait. The point of a wedding photo was to show the happy couple, not to hide half of it. And yet here was a bride who had gone to the trouble of wearing a beautifully made gown and posing in an ornately decorated studio—only to make sure no one could see her face.

Rebecca’s instincts, honed by years in homicide and now in the Chicago PD’s cold case unit, whispered the same thing:

Something’s off.

Without overthinking it, she bought the photograph.

Later, she would say that the moment she picked it up, she felt a faint, irrational chill, as if she were holding a piece of evidence rather than a cute piece of antique decor.

At the time, it was just an odd gift idea.

2. A Name on a Marriage License—and a Sudden Death

Back at the station, curiosity got the better of her. Instead of taking the photo home, she brought it to the cold case unit’s evidence lab.

“Come on, Walsh,” one of her colleagues teased. “You digging into 1912 now?”

“Off duty,” she said. “Just… indulging a weird hunch.”

She scanned the photograph at high resolution. The studio stamp matched what Murphy had said: Harrison Photography, Chicago. Date: June 22, 1912.

The groom’s face was sharp and clear. On a whim, she ran his image through facial recognition software, not expecting much. Unsurprisingly, the algorithm came up empty; digital facial recognition doesn’t do miracles with century-old photos.

So she went old school.

Using the date and place, she pulled up Cook County marriage records from 1912.

It didn’t take long.

On June 22, 1912, a 52-year-old widower named Thomas Whitmore married a 35-year-old woman named Helen Stone in Chicago. He was listed as the owner of Whitmore Manufacturing, a successful furniture company. Newspaper society columns from early 1912 mentioned the engagement of “prominent businessman Thomas A. Whitmore” to “Miss Helen Stone, recently of St. Louis.”

So far, so normal: an older widower, a younger bride from out of town.

Then Rebecca checked death records.

Thomas A. Whitmore died on July 15, 1912. Less than a month after the wedding.

Cause of death: heart failure.

Old for the era? A bit. But he was only 52, hardly a frail old man. The notes indicated he died “suddenly at home.” The attending physician, a family doctor who had known him for years, signed off. No autopsy. Quick burial. Private funeral.

His obituary named his recent bride, Helen, as his sole survivor.

Curiosity turned into suspicion.

She pulled property and probate records. Within two months, Helen Whitmore had inherited everything—Thomas’s house, his company, and his bank accounts—and liquidated it all. The house was sold, the business transferred to a new owner, accounts closed.

After September 1912, the paper trail went cold.

No forwarding address. No remarriage record. No death certificate. No trace.

A man in his fifties married a younger woman whose face we’ve never actually seen. Three weeks later, he was dead. She walked away with his entire estate and vanished.

One odd occurrence? Maybe.

Rebecca’s instincts insisted: Check where she came from.

3. A Pattern Hiding in Plain Sight

The marriage record and the society column both said the bride had come from St. Louis.

So Rebecca went digging.

In March 1911—just over a year earlier—a St. Louis newspaper carried a small announcement: Robert Mitchell, 48, a business owner, had married a woman named Margaret Stone. Two months later, he was dead. Official cause: heart failure. His widow inherited his estate, sold off his house and business, and disappeared.

Different city. Different first name. Same last name.

Same pattern.

Her pulse quickened as she widened her search.

Indianapolis, September 1910: James Harrison, 55, banker, married a woman named Katherine Stone. Six weeks later, he died of heart failure. She inherited. Sold everything. Left town.

Kansas City, May 1910: William Bradford, 50, merchant, married Elizabeth Stone. Dead within a month. Heart failure. His widow liquidated assets and vanished.

By now the path was clear: a woman using different first names but some version of the last name Stone was marrying wealthy middle-aged men across the Midwest. Within weeks, they died of “natural causes.” She inherited their money and disappeared.

Every time, the death certificate said “heart failure.”

Every time, no autopsy.

Every time, a different city.

By the time she reached Chicago in 1912, this mysterious woman had likely killed at least six men—and possibly more in places where records were incomplete or missing.

The photograph on Rebecca’s desk was suddenly not just a quirky antique. It might be the only surviving image of a serial killer.

And the killer’s face was still hidden.

4. Secrets in the Lace

If the bride had gone to such extremes to conceal her face during a formal portrait, she had probably done the same in everyday life—avoiding photography, controlling how she appeared in public, moving often and quickly.

But Rebecca had something early-twentieth-century cops didn’t: modern imaging software and an officer’s stubborn curiosity.

She pulled the scanned image back up, zoomed in tight on the veil, and stared.

The lace was unusually thick, with complex patterns and a faint glimmer.

She boosted the contrast and brightness. Tiny reflective threads lit up.

Photography in 1912 required long exposures—several seconds of stillness to capture an image. That meant anything shiny in the scene could pick up and hold faint reflections, like a primitive mirror.

What if the veil, heavy with reflective thread, had recorded more than just creamy white cloth?

Rebecca zoomed closer and began manipulating the image. She used filters to isolate certain ranges of light and shadow, then overlaid and sharpened them.

Slowly, something began to emerge.

Human features.

Not the bride’s—these faces weren’t full-on, but small, partial, like ghostly impressions caught in the folds and curves of the lace. A man’s forehead here. Another’s chin there. A pair of eyes in a different fold.

She stitched the fragments together digitally, flipping, rotating, and enhancing where needed.

When she was done, she had six distinct male faces—each faint, each incomplete, but real enough to count.

Her first thought was that the veil must have reflected photographs that had been nearby during the portrait session—framed pictures on a studio wall, perhaps. But then she looked more closely at their styles and clothing. These weren’t random strangers; they looked like formal portraits of upper-middle-class men from about the same era as the groom.

She compared them to the photos she’d already found in old newspaper archives: Robert Mitchell of St. Louis, James Harrison of Indianapolis, and William Bradford of Kansas City.

Three matches.

The jawline. The hair. The mustache style. Close enough that, if this had been a modern photo lineup, a prosecutor would have smiled.

The other three men in the veil didn’t match anyone in her files—yet.

She went back to the archives.

Cincinnati, 1909: George Sullivan, a well-off businessman, married a woman named Emma Stone, died shortly thereafter. Heart failure. Widow vanished.

Detroit, 1909: Henry Morrison, wealthy investor, married Anna Stone, dead within weeks. Widow inherited everything and disappeared.

Louisville, 1908: Charles Bennett, successful store owner, married Lydia Stone. Same result.

With those names added, the pattern stretched further back in time and space. Eight men now, in eight cities, from Louisville to Chicago, between 1908 and 1912.

All wealthy. All in their late forties to mid-fifties. All recently remarried to a woman using some variant of the last name Stone. All dead within weeks of the wedding. All listed as heart failure.

The veil in the 1912 portrait, it seemed, was not just hiding the bride’s face.

It was showing her past.

5. Science vs. the Causes of Death on Paper

The question now was brutal and simple: How had she killed them?

The pattern screamed poison. In that era, before advanced cardiology and toxicology, slow poisoning could easily pass for natural illness.

There was, however, one way to answer definitively—if she could get a judge to allow it.

Exhumation orders.

It wasn’t an easy sell. These were century-old graves, and the victims had descendants who would need to be informed and, ideally, consulted. There were questions of cost, public interest, and the ethics of disturbing the dead.

But this was Rebecca’s job: to stand up for victims who could no longer speak for themselves. Here, she argued, were at least eight men who had likely been murdered, their deaths written off as bad hearts while their killer disappeared into history.

With support from her commanding officer and the Cook County State’s Attorney’s Office, she filed the paperwork.

The first grave to be opened was that of Thomas Whitmore, buried at Graceland Cemetery in Chicago. Thanks to early twentieth-century embalming practices—even crude ones—some soft tissue samples remained. Those were turned over to the county medical examiner’s lab.

Dr. Sarah Kim, a forensic toxicologist, ran a battery of tests.

The results were unambiguous.

Whitmore’s tissues contained massive amounts of arsenic.

Not a one-time dose, but the pattern you’d expect from chronic exposure over days or weeks—a slow, steady drip of poison. The kind of poisoning that often looks, to an untrained eye, like a progressive illness: fatigue, gastrointestinal distress, neuropathy, chest pain, irregular heartbeat.

Exactly the kind of symptoms a physician in 1912 might have chalked up to “heart trouble” in a middle-aged man under stress.

Rebecca received permission to exhume three more victims: Robert Mitchell of St. Louis, James Harrison of Indianapolis, and William Bradford of Kansas City. Each time, the toxicology told the same story: arsenic.

The Stone bride wasn’t just unlucky in love.

She was killing husbands, one after another, with a readily available poison that left minimal trace in an era before routine chemical testing.

During the early 1900s, arsenic-based compounds were sold openly as rat poison, insecticide, and even medicinal tonics. A woman could buy it over the counter, sign no logbook, and walk away with enough to kill several people. Mixed into food or drink in small quantities over time, it could weaken organs and mimic natural disease.

Assuming the doctor had no reason to suspect foul play, an autopsy would be unlikely. A simple “heart failure” or “natural causes” would go on the death certificate, and that would be that.

Whoever the mysterious “Stone” widow truly was, she had studied that reality and exploited it with chilling precision.

6. The Woman Behind the Veil

If “Stone” wasn’t her real name, who was she?

Rebecca knew she’d have to look before 1908, in the years leading up to the first likely murder. She began combing through older newspaper archives, insurance investigations, and missing persons reports from across the Midwest and Northeast.

That search took her to Pittsburgh.

In the 1907 archives of a Pittsburgh newspaper, she found a wanted poster reprinted from a broader law enforcement bulletin. The headline read:

WANTED – CLARA HOFFMAN

Suspected in the poisoning death of her husband, Friedrich Hoffman, a German-born machinist who had died after a brief illness. The poster stated that an insurance investigation had raised concerns. A belated autopsy revealed arsenic.

By the time authorities were ready to act, Clara had vanished.

The poster included a formal portrait of a young woman with sharp features, dark hair pulled back, wearing a high-collared blouse. The description listed her age as thirty, her height as five-foot-five, and noted she was “intelligent, well-spoken” and “capable of assuming different identities with ease.”

Rebecca stared at the photo and then at the wedding portrait from 1912.

Even though the 1912 bride’s face was hidden, there were clues: the slope of the shoulders, the shape of the hands, the way she held herself. The ages matched. The timing matched. The modus operandi matched.

She dug deeper.

Before she was Clara Hoffman, the wanted woman had been Clara Henshaw, born in 1877 in rural Pennsylvania. She’d married a local farmer, John Henshaw, in the late 1890s. He died in 1905 officially of influenza. It had looked natural at the time; no one questioned it. She collected a modest life insurance payout and moved to Pittsburgh, where she married Hoffman.

Hoffman had more money and a larger policy. When he died suddenly, the insurance company balked. The claim timing, the short marriage, and Clara’s behavior raised red flags. They ordered an autopsy. This time, the arsenic was found.

But by then, Clara was gone.

She vanished from Pittsburgh, leaving no forwarding address—as she would do so many times in the years to come.

The case stalled. Without her in custody, prosecutors couldn’t move forward. The wanted notices eventually grew stale. Files were closed. The names of her first two husbands became just two more entries in ledgers full of the dead.

Somewhere out in the world, Clara was adjusting her strategy.

Insurance claims had drawn attention. From 1908 on, she stopped chasing life insurance and started targeting men with wealth she could inherit directly: business owners, investors, merchants, bankers.

She changed her last name to Stone and began leaving fewer fingerprints on paper.

By the time she arrived in Louisville in 1908 as “Lydia Stone,” she had already killed twice and learned from her mistakes.

7. The Photographer’s Journal

One gap remained: the woman’s life after 1912. After Thomas Whitmore died and “Helen Stone / Whitmore” walked away with his furniture factory and his savings.

To track her movements, Rebecca turned her attention to the one place where Clara had been documented under her latest alias: the photographic studio where that strange wedding portrait had been taken.

The stamp on the photo read: Harrison Photography – Chicago.

A little digging revealed that the original owner, Edward Harrison, had died decades before—but his grandson, Michael Harrison, still lived in the city and operated a small modern photography business. Rebecca gave him a call, expecting maybe a family anecdote at best.

“My grandfather kept everything,” Michael told her. “Props, old lenses, even his business journals. Let me see what I can find from 1912.”

Two days later, he called back.

“You’re not going to believe this,” he said. “I found the entry for that wedding. He wrote about it in detail.”

Michael invited her over. In his small office above a camera store, he laid a leather notebook on the desk, open to a page dated June 22, 1912.

In careful, looping handwriting, his grandfather had written:

“A most unusual wedding session today. Mr. Thomas Whitmore, a well-known businessman, arrived with his new bride for their portrait. The bride refused to lift her veil. Mr. Whitmore looked uncomfortable, but went along with it. She said it was for ‘religious reasons,’ but her behavior suggested otherwise—more like she was hiding something.

She held what appeared to be small photographs or paper clippings in her hands against her dress, concealed under the veil. She was very particular about the lighting and insisted on longer exposure times than I normally use. Mr. Whitmore seemed completely smitten, calling her ‘my dear Helen’ and speaking cheerfully of their honeymoon plans. She said very little, her attention fixed on making sure no part of her face was captured.

I have photographed many brides. Never one so determined not to be seen.”

Rebecca felt goosebumps rise on her arms.

“Do you still have the original glass plate negative?” she asked.

Michael nodded. “It was in the same box. Grandpa must have known it was unique.”

The glass plate, when scanned with modern equipment, revealed even more than the paper print.

The objects in the bride’s folded hands, which had looked like generic smudges on the original photo, snapped into greater clarity.

They were newspaper clippings.

Specifically, obituaries.

Carefully trimmed rectangles of newsprint, the inked edges visible when Rebecca boosted the resolution.

It seemed that on the day she married Thomas Whitmore—husband number eight—Clara had literally held the death notices of previous husbands in her hands.

Trophies.

And thanks to long exposure times and reflective threads, the faint reflections of the portraits that accompanied those obituaries had been captured in her veil.

She had built her own haunted monument and then sat for a photograph with it.

8. The Last Victim—and the Killer’s Final Mistake

Rebecca followed the trail forward from Chicago.

Property records confirmed that Helen/Clara sold Whitmore’s house and Whitmore Manufacturing by early September 1912. Based on the sale prices, she walked away with roughly $85,000—the equivalent of more than two million dollars today.

Where do you go when you’ve just scored the modern equivalent of millions and you’ve successfully killed eight men?

If you’re Clara, you go to another city—and do it again.

In Milwaukee, November 1912, a widower named George Patterson married a woman named Catherine Stone. One month later, he was dead. Heart failure. Estate to the widow. Widow gone.

And then, abruptly, the pattern stopped.

No more suspicious Stone widows in big-city marriage and death records. No more middle-aged wealthy men dropping dead within weeks of the wedding and leaving everything to a wife who vanished.

Rebecca considered the possibilities:

Had Clara moved to smaller towns with fewer detailed records?

Had she changed her method completely, dropping the rapid remarriage approach?

Had she been caught under yet another alias?

Had something—or someone—finally killed her?

She broadened her search.

In Portland, Oregon, in April 1913, she found a curious entry: a woman named Helen Stone had died in a local charity hospital. Cause of death: arsenic poisoning. Hospital notes described her as having arrived in critical condition, with symptoms consistent with heavy metal poisoning. No family had come forward. No ID beyond the name she gave. When she died within hours, the hospital staff arranged for a city burial in an unmarked grave.

To the overwhelmed medical staff, she was just another indigent patient.

To Rebecca, the timing, the name, and the cause of death screamed one thing: this was likely Clara, under one of her many Stone aliases, finally undone by the substance she had used to kill so many others.

Perhaps she’d miscalculated a dose intended for someone else. Perhaps she’d attempted suicide. Perhaps she’d been poisoned in revenge. The historical record was silent.

What it wasn’t silent about was the arsenic in her system.

With court approval, Rebecca arranged for the grave to be opened and the remains exhumed. DNA testing, cross-referenced with living descendants of Clara’s likely relatives in Pennsylvania (found through genealogical work and ancestry sites), would take months. But for the story, she already had enough to put the pieces together:

Clara Henshaw became Clara Hoffman, killed her second husband and fled.

Clara Hoffman became “Stone”—Elizabeth, Margaret, Katherine, Emma, Anna, Lydia, Helen, Catherine—killed wealthy men across eight cities from 1908 to 1912, always with arsenic, always inheriting, always disappearing.

And sometime in 1913, alone and anonymous in Portland, she died from the same poison she’d used on her husbands.

Justice, in a dark, ironic way, had been served over a century ago.

9. Closing a Case 112 Years Late

One gray morning, in a conference room at Chicago Police Headquarters, Detective Rebecca Walsh stood at a podium with a 24-by-36-inch print of the 1912 wedding photo on an easel next to her.

Under the harsh fluorescent lights, the bride’s lace veil and the groom’s confident, oblivious expression looked almost surreal.

Reporters murmured, cameras clicked, and TV news logos glowed on small microphones lined up on the lectern.

“Between 1908 and 1912,” Rebecca began, “a woman using multiple first names and the alias ‘Stone’ as a last name married at least eight wealthy widowers across the Midwest. Within weeks of each wedding, the husband died. The cause in every case was listed as heart failure.”

She took them through the basics: the pattern, the arsenic, the exhumations that confirmed poisoning. She explained how easy it had been for a woman in those days to purchase arsenic from a pharmacy without scrutiny, and how physicians of the era often misattributed arsenic symptoms to natural disease.

Then she clicked a remote, and the screens behind her changed.

The close-up of the veil appeared, the enhanced image showing faint male faces woven into its folds. The audience leaned forward.

“These reflections,” she said, “match portraits of several of the known victims. We believe the veil captured them inadvertently, a product of long-exposure photography and reflective threads. The bride was also holding obituary notices for her previous husbands under the lace.”

It was grisly and poetic at once—exactly the sort of detail that would lead every story that night.

Rebecca wasn’t interested in theatrics for their own sake. She cared about the men whose lives had ended quietly, their murders never recognized.

She read their names slowly:

John Henshaw (likely)

Friedrich Hoffman

Charles Bennett

Henry Morrison

George Sullivan

William Bradford

James Harrison

Robert Mitchell

Thomas Whitmore

George Patterson

“In their time,” she said, “these men were remembered as victims of fate—of illness, of bad hearts, of sudden misfortune. They left families behind who never got answers. Today, we can finally say the words they never heard: they were murdered.”

A reporter asked how many victims there could be beyond the eight or nine identified. Rebecca admitted they might never know. Records from small towns, poorly kept ledgers, lost newspapers—Clara could have killed in places that left no trace for historians or detectives.

“But what we have now,” she said, “is a framework. A suspect. A method. A timeline. And enough forensic evidence to close these individual cases with confidence.”

Another reporter asked the obvious:

“Why does it matter now? Everyone involved is long dead.”

Rebecca was ready for that.

“Because the truth matters,” she said simply. “Because the families of victims deserve to know what happened, even generations later. Because history should remember not just the crimes, but the people who were lost. And because when we solve cases like this, we remind ourselves—and the public—that murder is not just a story. It’s a theft. Of a life, of a future, of trust.”

She didn’t say it out loud, but there was another reason: this is what good detectives do. They speak for people who can’t. Time doesn’t change that mandate; it just makes it harder.

10. The Woman in the Veil

In the months following the press conference, the case took on a life of its own in the media and online. True crime podcasts dedicated episodes to “The Bride with No Face.” Social media users shared the wedding portrait, speculated wildly about Clara’s psychology, and debated how many men she might have killed beyond those identified.

Historians weighed in, marveling at the sophistication of her crimes and the way she had used the limited social options available to women at the time. Feminist commentators argued over how to interpret her story—a woman in a patriarchal era exploiting marriage and the legal structures that treated wives as natural heirs. Others pointed out that nothing about poisoned husbands was feminist; it was simply murder.

To Rebecca, the armchair analysis mattered less than the fact that people were finally saying the victims’ names.

She also felt something else: a lingering fascination with the photo itself.

That veil.

That image.

The visual metaphor was almost too perfect: a woman hiding her identity while literally cloaking herself in the faces of men whose lives she’d taken, holding their obituaries in her hands as she prepared to do it again.

In a sense, Clara had created her own confession and memorial in one.

She’d also underestimated how technology and curiosity might someday expose it.

In 1912, nobody could have imagined that a detective in 2024 would zoom into the microscopic patterns of a lace veil and pull out faces from a century-old reflection.

No one expects to be seen through the details.

No one expects the background to become the evidence.

11. What a Photograph Can Hold

For most people, a photograph is a keepsake—an attempt to freeze a happy moment.

For detectives, photographs are snapshots of truth, full of small, telling details. The cigarette brand in someone’s fingers. The clock on the wall behind them. The kind of watch on their wrist. The reflection in a car window.

In this case, a studio photograph taken in 1912 was:

The only known image of a prolific, methodical serial poisoner.

A record of the day she married her last confirmed victim.

A physical object that unintentionally captured the faces of her previous victims.

The thread that, when tugged a century later, unraveled an entire criminal timeline.

Clara never stood trial. She never confessed. There are no interrogation transcripts, no jury verdicts, no prison records.

What we have is that one image and the web of evidence that radiates from it.

It’s tempting to view her as a kind of ghost—someone who existed only in the spaces between men’s lives. But she was real. She had a childhood, a first marriage, a first victim. At some point she crossed an internal line from “unhappy” to “willing to kill.” At some point she realized arsenic could open doors that would otherwise stay locked.

We don’t know what her first poisoning felt like to her. Regret? Fear? Relief? Power?

By the time she sat for her portrait as “Helen Stone” next to Thomas Whitmore, she had done it enough times that she felt confident enough to carry the proof in her hands.

Maybe on some level she wanted to be seen.

If so, she got her wish—just 112 years later than she expected.

12. A Detective, a Gift, and the Weight of History

In the end, Rebecca did give her mother the photograph.

Not the original studio print—that was logged into evidence—but a high-quality reproduction, printed and framed, minus the enhanced ghostly faces and obituary clippings.

Her mother, a retired history teacher, loved it.

“Look at that veil,” she said, peering closely. “You can’t even see her.”

“Yeah,” Rebecca said quietly. “There’s a lot you can’t see from the outside.”

Her mom glanced sideways at her. “You’re going to tell me the story eventually, right?”

“Eventually,” Rebecca said. “When I’m allowed.”

Later that night, alone in her apartment, Rebecca opened her laptop and scrolled through the files one more time: the marriage licenses, the death certificates, the toxicology reports, the faded obituary clippings, the wanted poster for Clara Hoffman.

She ended on the scanned image of the wedding photo.

The groom stands tall, oblivious to his fate, hand resting firmly on the bride’s shoulder in a paternal, almost possessive gesture.

The bride stands beside him, posture confident, face wholly hidden.

The veil falls, thick with lace and reflective thread, a beautiful lie hiding a deadly truth.

In the darkness of her living room, Rebecca Walsh thought about how many cases like this must be buried in archives, disguised as accidents, heart attacks, bad luck.

She also thought about the fact that every once in a while, with enough stubbornness and a little bit of luck, the past gives up one of its secrets.

Sometimes it happens because someone pulls the right file, asks the right question.

And sometimes it happens because a detective with a good eye goes shopping for a birthday present and notices that, in a wedding photo from 1912, a bride went to extraordinary lengths to make sure no one ever saw her face.

In the end, the photograph did what photographs do best.

It told the truth.

Not all at once, not to the people who posed for it, and not even to the generation that first held it.

But eventually.

Long after everyone in it was gone. Long after the killer died far from home, anonymous on a hospital cot. Long after the victims were laid to rest without justice.

The camera had captured more than anyone intended.

It just needed someone, more than a century later, to look closely enough—and refuse to look away.

News

My Family Missed My Wedding For My Sister, But My Castle Ceremony Changed Everything…..

My Family Missed My Wedding For My Sister, But My Castle Ceremony Changed Everything….. I was pinning my veil in…

The Germans mocked the Americans trapped in Bastogne, then General Patton said, Play the Ball

On a gray December morning in 1944, as snow fell over the forests of Belgium and Luxembourg, Allied commanders stared…

“Please Marry Me”, Billionaire Single Mom Begs A Homeless Man, What He Asked In Return Shocked…

The crowd outside the Super Save Supermarket stood frozen like mannequins. A Bentley Sleek had just pulled up on the…

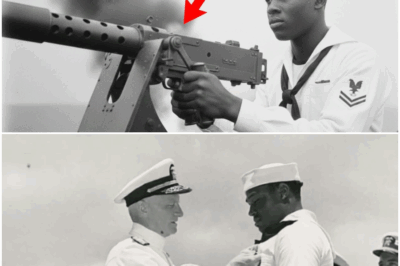

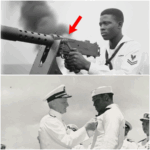

How One Black Cook’s “ILLEGAL” AA-Gun Grab Shook Pearl Harbor — And Forced the Navy to Change

On the morning of December 7, 1941, Pearl Harbor looked like a postcard. The water inside the harbor was calm…

She Was Serving Coffee in the Briefing Room — Then the Admiral Used Her Call Sign and the Room Froze….

She Was Serving Coffee in the Briefing Room — Then the Admiral Used Her Call Sign and the Room Froze…….

Japanese Couldn’t Hit This “Slow” Bomber — The Pilot Shot Down 3 Zeros and Sank Their Carrier

At 7:30 a.m. on May 8, 1942, Lieutenant (junior grade) Stanley “Swede” Vejtasa tightened his harness in the front cockpit…

End of content

No more pages to load